The Colorado Gold Rush, often known as the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, was a gold rush which occurred in the Pike’s Peak region of central Colorado in the United States. It was at its most intense between 1858 and 1862, though it continued through much of the 1860s. At the time these lands in the Rocky Mountains lay around the conjunction of the Nebraska Territory and Kansas Territory. It was only because of the gold rush that the Colorado Territory was created, in large part because of how much migration had taken place to the Rocky Mountains as gold fever set in during the late 1850s and early 1860s. The gold rush drew tens of thousands of people to Pike’s Peak in the space of a few years. It was responsible to a large extent for the region being settled and for Colorado quickly gaining admission to the Union as a state in 1876. As such, the Colorado Gold Rush was a key episode in the settlement of the Rocky Mountains and Colorado in the second half of the nineteenth century. Major urban centers like Denver were first established in Colorado during the era of the gold rush.[1]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Colorado Gold Rush chronology of eventsColorado Gold Rush chronology of events

The region which is encompassed by the US state of Colorado today was not a part of the United States until the middle of the nineteenth century. The Spanish, and later independent Mexico, had laid nominal claim to this area since the sixteenth century, but it remained largely untouched by European settlement. Instead it was Native American groups such as the Ute, Arapaho and Cheyenne who lived across the Rocky Mountains here. All this started to change in the late 1840s. The United States secured control over a vast stretch of territory running from Texas all the way west to California and Oregon at the end of the Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848. The peace in 1848 coincided with the discovery of gold out in California, which ushered in the California Gold Rush and the opening of the American West as hundreds of thousands of people migrated westwards from the East Coast or the Midwest towards the Rockies and the West Coast.[2]

Colorado did not experience much settlement during this period. Instead trading stations and supply outposts inhabited by no more than a few people sprang up along the region to sell food and supplies to those headed out further west to California. What changed matters was when a seam of gold was found in 1858 at Pike’s Peak, one of the largest peaks in the Rocky Mountains, around a hundred kilometers south of modern-day Denver. News spread fast and before long tens of thousands of gold prospectors and others seeking their fortune headed out to Pike’s Peak.[3] Many came from the east, though others came from the west, they being prospectors who had exhausted the possibility of finding riches in California by the end of the 1850s.[4] The gold rush at Pike’s Peak was most intense for three years until around 1861 and 1862. By then it was becoming clear that whatever easily available gold was to be had on the mountain and the streams running down from it had been exhausted and many people decided to move on to more promising ventures. However, those who remained continued to find less easily accessible gold for many years to come and the gold rush lasted in some ways until the end of the 1860s.[5]

Extent of migration during the gold rushExtent of migration during the gold rush

The extent of the level of migration to the Rockies and the region around Pike’s Peak is debated. The higher estimates suggest as many as 100,000 people flocked to Colorado from late 1858 onwards down to the mid-1860s, the bulk arriving between 1859 and 1861. Others argue for a much lower number that could have been around 40,000 or 50,000 people. In any event, many of these were transient and simply came for the boom years at the tail end of the 1850s and start of the 1860s before leaving again quite quickly, drawn to other rushes like the silver rush beginning at Comstock Lode in Nevada.[6]

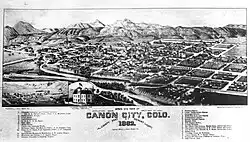

What’s clear is that the migration was significant enough that it led to the establishment of numerous prospector camps on the slopes of the Rocky Mountains, while larger and more permanent settlements began to appear around the Colorado region, notably at Denver, Boulder and Canon City. By the start of 1861 the level of migration to the region was substantial enough that the Colorado Territory was established in late February of that year. The creation of incorporated territories like this was part a major step in the second half of the nineteenth century towards parts of the American West being formed into states. The Colorado Territory had one of the shortest passages from being a thinly populated and unincorporated land in the 1850s, to becoming an incorporated territory in 1861 and then becoming the 38th state in the Union in 1876. The Colorado Gold Rush and the level of migration which it brought to Colorado and the Rockies was a major factor in Colorado’s swift passage to statehood and extensive settlement.[7]

Demographic impact of the gold rushDemographic impact of the gold rush

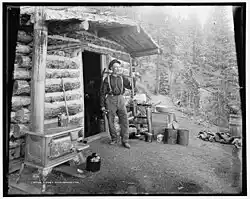

The demographic impact of the Colorado gold rush was great. This was early in the era of the American West and Colorado was barely settled in any fashion by Europeans at that time. People largely viewed it as nothing more than a mountainous region that needed to be passed through on the way out west to California and Oregon. The Colorado gold rush changed all that and made Colorado an actual center of habitation. There were only a few thousand non-native people living here in the 1850s prior to the gold rush. By the time Colorado was admitted as a state in 1876, the population had increased to around 194,000. It exceeded 400,000 at the end of the 1880s and by 1900 it was 540,000.[8] Denver had become a major urban center, with approximately 130,000 people living there by the end of the century.[9] Other sites of settlement boomed during the gold rush and then declined to become modest provincial towns, most notably Canon City just to the south of Pike’s Peak. Other temporary gold prospector camps simply turned into ghost towns once the gold rush ended.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the Colorado Gold RushExplore more about the Colorado Gold Rush

- 1885 Colorado State Census records collection on MyHeritage

- Colorado, Denver Deaths, 1880-1909 records collection on MyHeritage

- Colorado, Divorces, 1878 - 2004 records collection on MyHeritage

- Western United States, Marriage Index, 1838-2016 records collection on MyHeritage

- Colorado, Denver, Riverside Cemetery Burials records collection on MyHeritage

- Miners, Cattlemen, Merchants and More: Find Your Colorado Roots at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

References

- ↑ Wayne C. Temple, ‘The Pikes Peak Gold Rush’, in Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Summer, 1951), pp. 147–159.

- ↑ Andrea Isenberg, ‘The California Gold Rush, the West, and the Nation’, in Reviews in American History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (March, 2001), pp. 62–71.

- ↑ Ralph P. Bieber, ‘Diary of a Journey to the Pike’s Peak Gold Mines in 1859’, in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 14, No. 3 (December, 1927), pp. 360–378.

- ↑ E. J. Garbella, ‘Gold Placer Mining in Colorado’, in The Military Engineer, Vol. 24, No. 138 (November – December, 1932), pp. 558–560.

- ↑ Temple, ‘The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush’.

- ↑ https://www.historycolorado.org/story/2020/12/04/immigration-colorado-myth-and-reality

- ↑ Eugene H. Berwanger, The Rise of the Centennial State: Colorado Territory, 1861–76 (Champaign, Illinois, 2007).

- ↑ https://depts.washington.edu/moving1/Colorado.shtml

- ↑ https://physics.bu.edu/~redner/projects/population/cities/denver.html