The Eritrean-Ethiopian War was a conflict which was fought between Eritrea and Ethiopia between May 1998 and June 2000. The war came about primarily because of unresolved border issues following the end of the three decades’ long Eritrean War of Independence (1961–1991). In particular the Badme region along the border between Eritrea and the Tigray-dominated parts of northern Ethiopia was a point of contention. After clashes here in May 1998, Eritrea invaded Ethiopia. This was a poor decision by a country with a population about 3% the size of that of Ethiopia. After a lackluster start the Ethiopians pushed into Eritrea in 1999 and the Eritrean government accepted a ceasefire when the Ethiopians were advancing on their capital, Asmara, in the summer of 2000. Peace returned the situation to the status quo before the war. Border clashes would continue until a new peace summit in 2018. More broadly, the conflict entrenched military conscription and totalitarianism in Eritrea, a repressive system which has led to the flight of several hundred thousand Eritreans from their country over the past quarter of a century.[1]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Eritrean-Ethiopian War chronology of eventsEritrean-Ethiopian War chronology of events

The Eritrean-Ethiopian War broke out as a residual conflict from unresolved issues at the end of the Eritrean War of Independence. Eritrea was a colony of Italy between the 1880s and 1941. Thereafter it was administered for a decade by Britain before being given essentially to Ethiopia, which then ruled it as part of the Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea between 1952 and 1962. Ethiopian rule and ethnic tensions provoked the outbreak of the Eritrean War of Independence in 1961. This became a very long conflict, one which was exacerbated by the Ethiopian Revolution of 1974 and the Ethiopian Civil War that followed down to 1991. Eritrea only finally emerged victorious from the thirty-year long conflict when the collapse of the Soviet Union saw aid to the Marxist-Leninist Derg government of Ethiopia dry up and that regime overthrown. The United Nations then oversaw an independence referendum in 1993 in which Eritreans voted by 100% to become independent of Ethiopia.[2]

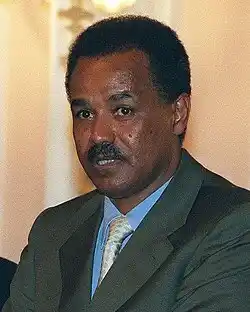

Although Eritrea acquired its independence de-facto in 1991 at the end of the war and had this confirmed by referendum in 1993, the manner in which the conflict had ended left many things unresolved between Eritrea and Ethiopia. There were, in particular, some questions about where the border lay and territorial disputes erupted on several occasions in the course of the 1990s. Furthermore, the Eritrean government began rounding up tens of thousands of Ethiopians and Eritrean women who had married or had children with Ethiopian men and forcibly transported them over the border to Ethiopia in the early 1990s. A commission was set up in 1997 to adjudicate on many of these issues. It was unable to resolve them and the Badme region along the border became an especial subject of friction. Violence flared here in early May 1998 and when several Eritrean soldiers were killed, the dictator of Eritrea, Isaias Afwerki, ordered the invasion of Ethiopia near the border at Badme. This was the start of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War.[3]

In response to the Eritrean incursion, the Ethiopian armed forces were fully mobilized for war with Eritrea. Ethiopian air strikes and attacks followed and fighting raged along the border regions through the summer of 1998. A joint initiative by the United States and Rwanda to broker a peace deal was rejected by Eritrea early in 1999. This was a major mistake. When the war resumed in February 1999 it became more intense and Ethiopia made major advances into Eritrea. Then their progress stalled slightly as both sides became bogged down in trench warfare reminiscent of the Western Front in France during the First World War. Ultimately, however, superior Ethiopian resources won out. It was a country of about 65 million people at the time. Eritrea had an estimated population of between two and two and a half million inhabitants. Given this population disparity, it could never win a prolonged war of this kind.[4]

By the early summer of 2000 the Ethiopian armed forces had advanced to within around 100 kilometers of Asmara, the capital of Eritrea. At this juncture the Eritrean government suddenly agreed to accept a framework for peace which had been laid out by the Organization of African Unity. The war was declared to be over and peace negotiations began in the city of Algiers in Algeria. The Algiers Agreement that was signed here in December 2000 was remarkably successful for Eritrea. Even though they had started the war and then comprehensively lost it, under the terms of the agreement both sides simply returned to their pre-war borders and accepted that a commission would be established to adjudicate on the contentious regions. When it returned its findings in 2002, Badme, the flare point of the war in 1998, was awarded to Eritrea.[5] Border clashes continued to arise periodically between the two nations throughout the early twenty-first century until these were finally resolved at a peace summit in 2018.[6] There are still regular reports of war potentially breaking out afresh between the two nations.[7]

Extent of migration caused by the Eritrean-Ethiopian WarExtent of migration caused by the Eritrean-Ethiopian War

The war between Eritrea and Ethiopia at the very end of the twentieth century caused a considerable amount of displacement along the border regions, though it never fully reached the capital of Eritrea, Asmara, where a very substantial proportion of the country’s population live, nor the coastal regions along the Red Sea. Therefore, the amount of people who were displaced was somewhat minimal and corrected itself once the fighting ended. Still, the war has had longer term migratory implications. Chastened by the memory of its defeat in 2000, the Eritrean government maintains a system of national conscription which requires all adult men and women to serve for a minimum of 18 months, though in practice most are required to do so for much longer.[8] This, along with the country’s economic woes and its totalitarian rule (which regularly sees it being deemed to be one of the most repressive regimes in the world by international rights’ organizations), has led to a situation where there is a constant stream of people fleeing from Eritrea to Ethiopia and other countries.[9]

Demographic impact of the Eritrean-Ethiopian WarDemographic impact of the Eritrean-Ethiopian War

While there has been a major stream of people out of Eritrea over the last quarter of a century, it is very hard to determine what the demographic impact of this has been, as the Eritrean government has never carried out a national census. It is believed that the population there is around three and a half million people today. This is a substantial increase on what it was in the late 1990s and so the flight of tens of thousands of Eritreans from their homeland would seem to have only slowed the rapid growth in Eritrea’s population. Elsewhere it has led to the emergence of large Eritrean communities abroad. There are upwards of 200,000 Eritreans in Ethiopia today and around 150,000 in Sudan.[10] Eritreans have also continued to travel to Germany, where they have joined a substantial Eritrean diaspora community that was first established there back in the era of the Eritrean War of Independence between 1961 and 1991.[11]

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the Eritrean-Ethiopian WarExplore more about the Eritrean-Ethiopian War

- Remembering Eritrea-Ethiopia border war: Africa's unfinished conflict at BBC News

- The 1998–2000 Eritrea-Ethiopia War and Its Aftermath in International Legal Perspective at Springer Publishing

- A Year After the Ethiopia-Eritrea Peace Deal, What Is the Impact? at United States Institute of Peace

- Are Ethiopia and Eritrea on the Path to War? at Foreign Policy

References

- ↑ Adrien Fontanellaz and Tom Cooper, Ethiopian-Eritrean Wars, Volume 2 (Warwick, 2018).

- ↑ https://www.thecollector.com/eritrean-war-of-independence/

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-44004212

- ↑ Sean D. Murphy, ‘The Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998–2000)’, in Oliver Corten and Tom Ruys (eds.), International Law and the Use of Force: A Case-Based Approach (Oxford, 2006).

- ↑ Jon Abbink, ‘Badme and the Ethio-Eritrean Border: The Challenge of Demarcation in the Post-War Period’, in Africa, Vol. 58, No. 2 (June, 2003), pp. 219–231.

- ↑ Martin Pratt, ‘A Terminal Crisis? Examining the Breakdown of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Dispute Resolution Process’, in Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol. 23, No. 4, Special Issue: Territorial Conflict Management (Winter, 2006), pp. 329–341.

- ↑ https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/07/ethiopia-eritrea-war-tplf/

- ↑ https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/09/eritrea-crackdown-draft-evaders-families

- ↑ https://mg.co.za/thought-leader/2023-12-22-the-flight-of-young-eritreans-is-destroying-the-countrys-human-capital/

- ↑ https://data.unhcr.org/en/country/eth

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-66145900