Could a gay or lesbian relative exist in a family tree? LGBT (lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, and transgendered) people can be found when researching genealogy, but the search syntax, keywords and strategies are very different. By understanding the basics of “gay history” as well as how LGBT folk lived, worked, and socialized, researchers not only locate these relatives, but realize the importance of preserving their stories.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Why LGBT family history stories matterWhy LGBT family history stories matter

Does it really matter knowing more about a LGBT ancestor and their activities? What value could such information add to the overall information about that person? For those seeking an entire picture of an ancestor using genealogy-related records, details as to sexuality and lifestyle do matter, especially if they had an impact on major life decisions including employment and relationships.

The pursuit of such information is valid for another reason: future generations of genealogists may become so accustomed to personally knowing self-identified LGBT folk and may take the existence of same sex marriages for granted, that they won’t know what to look for when it comes to older records. Even now, younger generations seem to take much about LGBT lifestyles for granted. Often they don’t understand what it was like to live and act and talk in “Code” as a means of survival or that there were life and death consequences to being “outed.”

Genealogists committed to serious research involving a possibly gay ancestor should take time to consider how to use the information they find and how the information will be shared. There isn't a proper way to “out” a deceased gay aunt or bisexual uncle; in fact, it is a matter of presentism creeping into one’s research that makes many believe a relative would identify themselves as homosexual if they were alive today. For non-LGBT people it is difficult to understand all the issues involved with daily life “in the closet” or the impact of “coming out.” Outing a gay ancestor may not be the best way to preserve that person's memory, let alone share family history with their living relatives.

Understanding LGBT historyUnderstanding LGBT history

Before researching various records, either in person or online, do some basic background reading on the history of LGBT people in the United States or other countries. Many people—even members of the gay community—are unaware of “queer history” and how it shaped their community and impacted the history of the United States. Here is a glimpse at some more recent history:

- World War II played an important role in gay history. During the war, men and women, normally turned away from military service for their sexuality, were pressed into service in order to help win the war.

- Between 1939 and 1945, large numbers of gay men and women who lived in isolation in rural areas had the opportunity to interact with others who were “just like them” thanks to military service.

- Look at current locations with large gay populations: San Francisco, New York, San Diego, Chicago, and Philadelphia. They were all important military installations during World War II. Many in the military saw their service end in these cities and simply stayed there and became part of the community.

- The military witch hunts of homosexuals returned once World War II was over. Pair this with the rise of McCarthyism and the Lavender Scare and it is apparent why talking and behaving under a “Code” continued to develop as a means of keeping a job or interacting with other LGBT folk.

- In most places, homosexuality was a crime; those suspected of being “queer” or “different” could lose their jobs and be shunned by their families.

- Prior to the 1950s, very few LGBT people lived a self-identified or “out” lifestyle or were open about a long-time relationship with someone of the same sex. Such information was only shared with a close group of friends, and possibly sympathetic relatives. It is difficult to find evidence of “out” individuals through public records.

- The “bar culture” was a huge part of the social world of gay men and women, and in many cities, such as New York, bars were controlled by the Mafia or other crime syndicates. Gays were often extorted for money or blackmailed. Police officers were paid off to look the other way when it came to gay bars. When a raid did happen, it often resulted in some bar patrons having their names, addresses and occupations published in the newspaper.

- The Stonewall Riots in June 1969 are considered a watershed moment in gay history. Taking place in Greenwich Village in New York City, Stonewall at its core was a rejection of the status quo when it came to how LGBT people were treated by society. Led by a group of drag queens during yet another police raid on the Stonewall Inn bar, the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots is marked annually on the last Sunday in June as Pride Day.

- In the post-Stonewall era, the gay rights movement started. Over the subsequent four decades advancements have been made in terms of rights concerning marriage, adoption, and employment for LGBT people.

LGBT sub-cultures and "The Code"LGBT sub-cultures and "The Code"

The term “Code” or “The Code” is often used to designate slang, terminology, and code words that one learned as they navigated the various subcultures in the LGBT culture. Since homosexuality was illegal and being identified as homosexual, aka “outed,” had many ramifications in terms of employment and societal integration, a secret language developed among gays and lesbians. For example: Polari is a slang language developed in Britain and used by gays as well as performing artists, criminals, prostitutes and others living on the margins of society. Polari as a language has roots as far back as the 16th century and is still in use today; many practitioners say it is an “attitude” more than a language, much like the current Drag culture. Today’s “Code” is marked by phrases, vocabulary, and gestures some of which have made it into mainstream culture thanks to greater acceptance of LGBT people, especially as portrayed by the media.

As with many underground cultures, various LGBT subcultures developed over time. Studying and knowing the differences between the gay male culture, the lesbian culture, the transgender culture, etc. is vital to “decoding” information, especially in personal letters and diaries. Some of these subcultures, to the outsider, are often seen as “deviant” or tend to reinforce stereotypes about gays and lesbians. Put aside preconceived notions when investigating a subculture. As with any reference material, take note of items that can later help locate information about a gay ancestor.

Understanding language related to LGBT life can offer many clues when looking at records or reviewing personal letters and diaries. The same holds true for the various queer subcultures: many had their own Code, their own practices and even their own symbols and forms of dress.

LGBT locations and neighborhoodsLGBT locations and neighborhoods

Many of our immigrant ancestors flocked to specific neighborhoods when they arrived in America. The reason? They felt safer with those who spoke their language and kept the same customs as in the Old World. These neighborhoods in large urban areas often had strict dividing lines and offered a “step up” on the path to becoming an American citizen and being successful.

The sense of belonging in a geographical sense was, and to some extent is, still true for LGBT men and women. Certain districts in cities such as New York (Greenwich Village) and San Francisco (The Castro) are where newcomers would settle in order to be closer to the LGBT culture. Again, don’t fall victim to presentism when it comes to noting the “gayborhood” in which an ancestor may have lived. Research the neighborhood designated as the "gay ghetto" during a person's time in that location. For example, The Castro was not a predominantly gay neighborhood until the early 1970s; prior to that time the Polk Gulch area is where bars, bookstores and other LGBT hangouts could be found and where LGBT people lived.

LGBT occupationsLGBT occupations

What may not be apparent to “straight eyes” are the realities of earning a living for many LGBT persons. And there are good reasons why "hairdresser" or "florist" were stereotypical gay male professions.

Legally, a person could be fired for being a homosexual in many locations in the United States up until recently. For that reason, many homosexual men and women earned a living as small business owners—florists, hairdressers, etc.—in which they were the boss and knew they would not be fired based on their sexuality. In addition, certain professions, such as working in a barber shop or hair salon, were “portable,” meaning there was little inventory (a good set of barber tools) and the person could pick up and work in another city if needed.

There were specific professions—in the art and design fields, for example—where gay men and women could meet other gay men and women. In department stores, males behind the counter were “salesmen,” but were often called “ribbon clerks” as part of gay slang and The Code. Look for bars near these large stores as places for socialization after work. Often on census sheets, the general term “artist” was used as opposed to “set designer” or “interior decorator” or “fashion designer.”

In some cases, the partner of a gay man or woman might be listed as an employee such as a “private secretary” or “assistant” and listed under the head of household. Also, a place of employment might be listed as “in a private home” or “for a private family.”

Clues in mementoes and items left behindClues in mementoes and items left behind

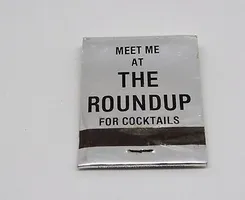

Some family members may have inherited from their LGBT ancestor or relative a group of letters, diaries, or even small collections of items such as match book covers and ticket stubs to plays and performances. Read through letters and diaries and remember “the Code,” and look for specific occupations as well as geographical locations that were historic gay neighborhoods.

A matchbook cover could be from a local gay bar or a bar that was LGBT-friendly. For those unacquainted with the “bar culture” in the LGBT community, realize that these bars were more than just places where a person could get a drink and meet someone: they often acted as social clubs and places where gay rights meetings were held and marches or protests were planned.

So what might look ordinary when it comes to belongings may require further research with an eye toward LGBT culture, subcultures, and history.

Using the F.A.N. Club research strategyUsing the F.A.N. Club research strategy

The best success in determining that an ancestor may have been gay, bisexual or transgendered is to rely upon the F.A.N. Club approach: tracing Friends, Associates and Neighbors of the person in question. Remember that LGBT folk often lived in the same neighborhood, may have run in the same social circles, and often worked in specific fields and occupations.

There is no such thing as a “gay record” when it comes to genealogical research. Researchers need to build a body of LGBT knowledge to be successful in locating records which may indicate that a person was a homosexual.

- Starting with the 1940 United States Census, the term “partner” could be used to indicate someone living in the household that was not a blood relation. However, it is more likely that the terms “boarder” or “roomer” were used.

- Look for occupations on military records and census records that represent “queer work” as described above.

- Passenger lists, especially for steamship travel in the early 20th century, may show two people of the same sex living at the same address with no children or family.

- Check the address listed in voting registers, city directories, telephone books, and even census schedules. Does it fall within a traditional gay neighborhood?

- Again, in census schedules, note children of adult age who are unmarried living with older parents or a married couple showing no history of children.

- Military records, especially if a discharge was less than honorable, can hold important clues as well.

- Passport records can offer clues. With no children of their own, some gay men and women had more disposable income and tended to travel more. For passport applications, check the identity of the person verifying that the applicant is a United States citizen and that they have known that person for a specific amount of time. Often, this person has a F.A.N. Club connection to the person.

- Newspaper records are a good source of obituary and death notice information. In addition, and unfortunately, any arrests of homosexuals would be detailed as front-page news in some communities.

Conclusion: Things were different thenConclusion: Things were different then

The term homosexual was not in use until 1869 (coined by Hungarian journalist Karl-Maria Kertbeny). What we understand in the 21st century when it comes to how LGBT people identify themselves today would likely be foreign to many LGBT people prior to the 1940s.

Living in a “marriage of convenience” was part of being in the LGBT subculture as was working in certain professions. So was knowing “The Code” and passing that knowledge on to others new to the LGBT community. Looking back at how LGBT ancestors lived may, in fact, make some people feel pity for them, expressing sadness knowing that they took certain actions based on strict societal expectations. Again, avoid comparing how LGBT individuals in the past lived with how members of today’s LGBT communities conduct their lives.

Try to accurately research all aspects of an ancestor or relative's life and when discovering evidence of a possible LGBT lifestyle outside of the expected norm of the time, preserve the information and determine if it truly adds to the entire picture of a person's life. And then add it and make it available for future generations of researchers.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about exploring LGBT family historyExplore more about exploring LGBT family history

WebsitesWebsites

- Between the Lines and Through the Silences: Researching LGBT Ancestors, by Rich Venezia, Irish Lives Remembered, Spring 2017

- FamilySearch, same-sex marriage, and the risk of obsolescence, by Donna Cox Baker, 10 November 2016, The Golden Egg Genealogist

- Forbidden Forebears: Finding the GLBT Ancestors in Your Family, by Michael J. Leclerc, 1 June 2013, Mocavo

- Gay and Lesbian Relatives, by Janice Sellers, 11 October 2012, Ancestral Discoveries

- Gay Genealogists, by Thomas MacEntee, 11 October 2011, Destination: Austin Family

- Gender Selection and the Impact on Future Genealogy Research, by Thomas MacEntee, 7 July 2017, Abundant Genealogy

- Genealogy in the Works: Being Gay in Genealogy, by Becks Koebel, 2 February 2017, Hipster Historian

- How to trace LGBT ancestors by Mary McKee, 28 November 109, Findmypast

- LGBT Genealogy, by Kim Cotton, 20 October 2011, Kim Cotton Research

- LGBT and Mafia, series of blog posts by Justin Cascia, Mafia Genealogy

- LGBTQ Genealogy, by Stewart Blandón Traiman, MD, Six Generations

- Lives between the Lines: Finding LGBTQ Family History, by Thomas MacEntee, June 2016, Pennsylvania Legacies, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Mormons Will Recognize Same-Sex Couples in Their Genealogy Database, by Tim Marcin, 18 June 2018, Newsweek

- Notable LGBT People, project at Geni.com

- OutHistory

- The Arquives – Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives

- The Gay Chronicles

- The Hidden - LGBT Family Members and Genealogy, by Thomas MacEntee, 17 October 2007, Destination: Austin Family

Books and ArticlesBooks and Articles

- Baker, Paul, Fantabulosa: A Dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004.

- Berubé, Allan, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II, Chapel Hill: Univ of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Bronski, Michael, A Queer History of the United States, Boston: Beacon Press, 2011

- Cante, Richard C., Gay Men and the Forms of Contemporary US Culture (Queer Interventions), Farnham (United Kingdom): Ashgate Publishing Co., 2008.

- Chauncey, George, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940, New York: Basic Books, 1994.

- Duberman, Martin, Stonewall, New York: Open Road Media, 2013.

- Gates, Gary J. and Jason Ost, The Gay & Lesbian Atlas, Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Press, 2004.

- Lifshitz, Sebastien, The Invisibles: Vintage Portraits of Love and Pride. Gay Couples in the Early Twentieth Century, New York: Rizzoli, 2014.

- Katz, Jonathan Ned, Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A., New York: Plume (Penguin Group), 1992.

- Mann, William J., Behind The Screen: How Gays and Lesbians Shaped Hollywood, 1910-1969, New York: Penguin, 2002.

- Scodari, Christine, Alternate Roots: Ethnicity, Race, and Identity in Genealogy Media, Chicago: American Library Association, CHOICE: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries (Vol. 56, Issue 6), 2019