Family traditions are an element of family history. Some traditions are purely cultural, such as culinary traditions or how different ethnic and religious groups celebrate certain holidays. These can be especially important for a person’s family history within diaspora communities where traditions from the old country are passed down from generation to generation to preserve a sense of a persons's heritage. Others can be useful for tracing a person’s family history and genealogy. For instance, family heirlooms like family bibles, old photographs, diaries or even something like an old pocket watch with an engraving on it, can provide information about one’s ancestry and heritage that otherwise might not be available. When these are passed on to the next generation it perpetuates these family traditions.[1]

Examples of family traditionsExamples of family traditions

Family traditions come in all different shapes and sizes, from rituals around holidays and the kind of food that is cooked on specific days to the passing down of heirlooms from generation to generation. These are a part of family histories and are often rooted in a family’s migration history, revealing much about their heritage. Perhaps one of the most striking examples of this is the Jewish coming of age ritual, bar mitzvah (masculine) and bat mitzvah (feminine). There are references to Jewish coming of age going back as far as the composition of the Tanakh and other Hebrew religious texts in the first millennium BCE, while celebrations akin to modern day mitzvahs were occurring in the Middle Ages. Therefore, a bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah, when held today in a city like New York or London, is a statement about the strength of family and communal traditions within the Jewish diaspora, ones which have persevered over millennia.[2]

The range of family traditions which inform one's family history, ancestry and heritage are very considerable. A good example is the practice of keeping family bibles, something which became common in Protestant countries in particular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Often people would use a few of the blank pages in these to write out details of the births, marriages and deaths of family members, sometimes with additional details which can complement genealogical studies such as the names of godparents.[3]

Similar aspects of material culture that might be considered family traditions include the handing down of family heirlooms. Examples of these are watches and pocket-clocks passed from generation to generation or something like a family wedding ring or cuff links worn on the day of a wedding by several generations of a family. Military badges, service medals and paraphernalia are also often passed on in this way and can inform a family member generations later of the life story of his or her father, grandfather or great-grandfather.[4]

Another family tradition within diaspora communities is visiting sites which are at the core of a family’s history. It is, for example, very common for members of the Irish, Italian, Polish, German and other communities in the United States to travel back at least once in their lifetime to visit the place where their ancestors who first set off across the Atlantic to America came from. Curiously, this seems to be more common where the individuals came from villages or smaller towns, the more personal feel of a more rural setting providing a greater sense of place than it would were an Italian American visiting Naples or an Irish American Dublin. In countries like Ireland this has even resulted in a form of tourism referred to as genealogy tourism, in which people will visit the country on both a holiday and as a means of reconnecting with the place their family once hailed from.[5]

How family traditions can inform family historiesHow family traditions can inform family histories

Family traditions can inform family histories in many ways. To take the earlier example of bar and bat mitzvah, these re-enforce the Jewish heritage of individuals when celebrated. The same applies to a wide range of family traditions. The Italian diaspora is enormous today. Upwards of 100 million people worldwide claim Italian ethnicity, most especially in countries like the United States, Argentina and Brazil. Though they might be fourth, fifth or even sixth generation Italians in these countries, their ancestors having variously arrived there between 1860 and 1920, their connections to the old country are expressed through the Italian emphasis on close-knit families and Italian cuisine.[6]

Within the equally enormous Irish diaspora in places like America, Canada, Argentina, Australia, England and Scotland, Irish heritage is expressed in how families relate to elements of Irish culture abroad such as the celebration of St Patrick’s Day each year on the 17th of March.[7] Signs of how strong these familial and communal symbols of heritage can be seen in President Joe Biden’s recent visit to Ireland in 2023 to visit the home place of his great-great-grandfather, Patrick Blewitt, in Ballina in county Mayo.[8]

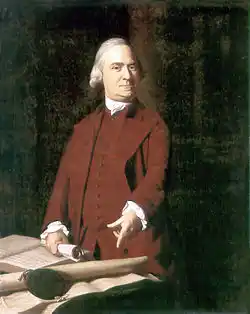

One of the most valuable family traditions from a genealogical perspective is the production of a time capsule. Imagine if you put a range of objects into a box and sealed it up for a century what your great-grandchildren would learn about their heritage that they didn’t previously know when they opened it. The first time capsules generally date to the eighteenth century, with examples having been uncovered in countries as far apart as Poland and Spain in Europe. A famous example was a time capsule created by one of the Founding Fathers, Samuel Adams, and another important figure from the American Revolutionary War, Paul Revere. In 1795 they buried their time capsule underneath the place where the cornerstone of the Massachusetts State House was laid down as the construction of that iconic Boston building commenced. Among other items, it contained newspapers from the late eighteenth century, coins dating back to the middle of the seventeenth century, some fine tableware and a copper medal which depicted George Washington, who at the time of the sealing of the time capsule was serving as the 1st President of the United States. Hence, this particular time capsule acted as a kind of record of the collective history at the time, not of a family but of a nation.[9]

See alsoSee also

Explore more about family traditionsExplore more about family traditions

- MyHeritage Family Sites records collection on MyHeritage

- Family Heirlooms records collection on MyHeritage

- Create Your Own YouTube Channel to Store and Share Family Videos at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Holiday Traditions from Around the World at the MyHeritage blog

- Preserving and Sharing Family Recipes + Recipe Contest! at the MyHeritage blog

References

- ↑ https://matteotalotta.medium.com/how-my-family-and-cultural-history-shaped-my-identity-8201b40c3e8

- ↑ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/history-of-bar-mitzvah/

- ↑ https://dp.la/news/family-bible-records-genealogy/

- ↑ https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/british-military-campaign-and-service-medals/

- ↑ https://www.irishexaminer.com/news/arid-41134279.html

- ↑ https://nuitalian.org/2023/12/13/italian-american-culture-through-the-tradition-of-food-a-historical-overview/

- ↑ https://thehistorypress.co.uk/article/the-irish-diaspora-and-st-patricks-day/

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-65270569

- ↑ https://www.history.com/news/time-capsule-buried-by-paul-revere-and-sam-adams-discovered-in-boston