Researching your Filipino-American family history can be an exciting journey. Filipino surnames carry a rich history influenced by indigenous cultures, colonial regimes, and migration to the United States.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Historical Development of Filipino SurnamesHistorical Development of Filipino Surnames

Pre-Hispanic Naming PracticesPre-Hispanic Naming Practices

Before Spanish colonization, Filipino naming conventions were very different from the Western system of inherited surnames. Early Filipinos often did not have fixed last names passed from parent to child. Individuals might be identified by their location or personal characteristics. These indigenous naming practices were descriptive and fluid, and there was no universal practice of inheriting a family surname.

Spanish Colonial Surname Reforms (Clavería Decree of 1849)Spanish Colonial Surname Reforms (Clavería Decree of 1849)

A major turning point came during Spanish rule. By the 19th century, the lack of consistent surnames had become problematic for colonial administration. Many Filipinos named themselves after saints, resulting in too many people sharing a few common names. In 1849, Governor-General Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa issued a landmark decree requiring all Filipinos to adopt permanent surnames for use in civil records. This decree was accompanied by the Catálogo Alfabético de Apellidos, an alphabetical catalog of approved surnames distributed throughout the islands. Families were instructed to select a surname from this list and use it henceforth for legal purposes. This is crucial for genealogists – if you trace Filipino ancestry beyond 1849, remember that earlier generations may have used a different naming system or a variety of surnames.

American Colonial and Modern InfluencesAmerican Colonial and Modern Influences

Spanish surnames remain extremely common in the Philippines today as a result of the 1849 reforms. However, not all Filipino surnames are Spanish in origin – some families retained indigenous names (such as Gatmaitan or Katigbak), and others have Chinese or other Asian roots due to centuries of trade and migration. When the United States took control of the Philippines in 1898, they brought the English language and American record-keeping practices. The basic naming pattern (inherited family surnames) stayed the same, but one change was in naming conventions on paper. Filipinos traditionally carry both parents’ surnames: under Spanish custom, a person might have a compound surname (father’s last name followed by mother’s maiden name). The American system simplified this by treating the father’s surname as the last name and the mother’s maiden surname as a middle name. For example, a child named Juan Santos Reyes would have Reyes (father’s surname) as his last name and Santos (mother’s maiden name) as his middle name in records. This adaptation is still used in the Philippines today and actually aids genealogy, since the middle name points to the maternal lineage.

Americanization of Filipino Surnames in the U.S.Americanization of Filipino Surnames in the U.S.

When Filipinos settled in America, their surnames sometimes underwent subtle changes, though not as drastically as some other immigrant groups. Most Filipino surnames were already written in the Latin alphabet and often of Spanish origin, so they were familiar to American English speakers. This meant officials at U.S. ports usually did not force name changes (the common Ellis Island name-change myth does not apply much to Filipinos). However, there were still a few adjustments that could occur:

- Spelling and Accent Marks: Filipino names containing Spanish letters or accents were usually adjusted to fit English conventions. For instance, the Spanish ñ in names like Muñoz or Peñalosa would typically be written as n (Munoz, Penalosa) in American records, since early typewriters and forms did not accommodate the ñ character. Likewise, diacritical marks (accented vowels) were dropped. These minor spelling variations mean you should check for alternate spellings of your surname in U.S. documents. A name like De Guzmán might appear as De Guzman (without the accent) or even Deguzman (merged into one word) in various records.

- Phonetic Variations: Some surnames or given names were written phonetically by English-speaking clerks. For example, a surname like Parungao might be misspelled if the pronunciation was unclear. Be open to slight differences – say, Gonzales vs. Gonzalez, or Reyes vs. Reyas – when searching records. It’s wise to search U.S. databases using wildcard characters or sound-alike options to catch these variations.

- Adoption of English Names: In general, Filipino surnames were not typically changed to entirely new English surnames (unlike some European immigrants who anglicized their names). However, given names were frequently Americanized (e.g. Juan becomes John, Guadalupe becomes Lupe or Gladys). Take note that an ancestor might be recorded under an English first name or nickname in U.S. records, while their Philippine documents use a Spanish or indigenous name. Women’s surnames may also appear differently if they married in the U.S. – a Filipina might be recorded under her married name in American records, whereas Philippine documents (like her birth certificate) would have her maiden surname.

- Middle Name Confusion: As mentioned, a Filipino middle name is the mother’s maiden surname, which is a clue to maternal ancestry. In U.S. records, this often appears as a middle initial or is omitted. For example, Maria Santos Cruz in the Philippines (Santos being her mother’s maiden name) might appear as Maria S. Cruz in American records. Researchers should be aware that the “middle initial” in a Filipino-American name could actually represent a family surname. If you see an unusual middle name in a record, consider that it might be the person’s mother’s maiden name. This insight can help you connect U.S. documents back to Philippine records which often include the mother’s maiden surname.

In summary, Filipino immigrants generally kept their last names, but you should be prepared for small changes in spelling or format. Understanding these nuances will help you recognize your family in historical documents even if the name isn’t written exactly as you expect.

Step-by-Step Guide to Researching Filipino-American Surname OriginsStep-by-Step Guide to Researching Filipino-American Surname Origins

Step 1: Gather Family and Oral History: Begin at home. Talk to your relatives – parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles – and collect any known information about your family’s roots. Ask about original names (including any alternate spellings or nicknames), the town or province in the Philippines where the family came from, and roughly when they immigrated to the U.S. Write down full names (including middle names, which as noted reflect the maternal surname), dates and places of birth, marriage, and death, and any stories of how the family came to America. Oral history can provide clues that aren’t in documents, such as old Filipino naming customs or reasons a name might have been changed. It can also guide your search to the right location in the Philippines. For example, knowing that your great-grandfather was from Cebu or Ilocos narrows down which local records you’ll need later.

Step 2: Search U.S. Immigration, Naturalization, and Census Records: Armed with basic information, dive into U.S. records for evidence of your Filipino ancestors:

- Passenger Lists and Travel Records: Look for your ancestor’s arrival in the U.S. via ship passenger lists or airplane manifests. Many early Filipino immigrants came by ship to Hawaii or California. Websites like MyHeritage.com and FamilySearch have passenger list databases. Search by name (keeping in mind spelling variations) and approximate arrival year. These lists often state a person’s last residence or home town – a critical link back to Philippine records.

- U.S. Census Records: Filipinos who lived in the U.S. should appear in federal censuses. The 1910, 1920, and 1930 U.S. censuses, for example, have entries for Filipino farm workers in California and students in other states. Later censuses (up to 1950, which is the latest currently public) can also be useful for post-WWII immigrants. Census records typically record each person’s birthplace (it might simply say “Philippine Islands” or a specific province) and citizenship status. Early 20th-century Filipinos might be marked as “Al” (alien) or “Na” (naturalized) or even “Pa” (first papers) in the citizenship column, or sometimes as "Philippine" under race/nationality since they were U.S. nationals. These clues tell you if and when they naturalized.

- Naturalization and Citizenship Papers: If your ancestors became U.S. citizens, their naturalization records are gold mines of information. A naturalization petition or certificate often includes the person’s original name, birth date and place (usually listing the town and country as “Philippines”), and sometimes even the ship name and arrival date. Note that before 1946, many Filipinos were U.S. nationals but not citizens, and laws barred Asian naturalization. After 1946 and especially after 1965, many did naturalize. You can find naturalization records via the U.S. National Archives (NARA) or request copies from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

- Draft and Military Records: Don’t overlook U.S. military records. Filipinos have served in the U.S. Armed Forces since the early 1900s. Draft registration cards (for World War I and II) often list place of birth. For example, a WWII draft card might say someone was born in “Iloilo, Philippine Islands.” Military service records or pension files, if accessible, can contain personal details and next-of-kin information.

- Other U.S. Records: Depending on where your family settled, consider local sources like marriage licenses, death certificates, or newspaper obituaries. A death certificate in the U.S. usually lists birth place and parents’ names (though the accuracy depends on the informant). Church records in Filipino-American communities (baptisms, marriages) may also list ethnic parishes or Filipino priests who kept notes of members’ origins.

All these U.S. sources help establish when your ancestor arrived and where in the Philippines they came from, which is essential for the next step.

Step 3: Use Philippine Civil Registration and Church Records: Once you identify a hometown or province in the Philippines, you can switch focus to records in that country to delve further back in the lineage:

- Civil Registrations: The Philippines has civil registration of births, marriages, and deaths. Civil record-keeping was introduced broadly in the early 20th century (American period) and became more systematic over time. Many civil records from the 1900s onward are stored with the Philippine Statistics Authority (formerly NSO). You can request copies of birth, marriage, or death certificates if you have enough detail (name, date, place). Keep in mind the record will likely be in English (for mid-20th century) or sometimes in Spanish for early 1900s forms. Civil marriage records during the Spanish period (particularly 1880s-1890s) and early American period have also been archived. Some of these historical civil records (from both Spanish and American eras) are available online through FamilySearch’s digitized collections.

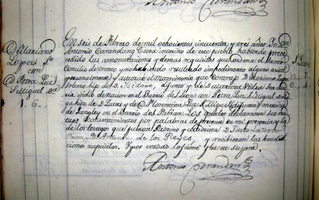

- Church Records: For earlier generations, church records are crucial. The Roman Catholic Church was the official keeper of vital records before civil authorities took over. Parish baptismal, marriage, and burial registers in the Philippines date back to the 1600s in some areas. These records are usually in Spanish (or sometimes Latin), especially those before the 1900s. For example, a baptism record from 1880 will list the child’s name, baptism date, parents’ names (the mother often with her maiden surname), and godparents, all written in Spanish script. FamilySearch has microfilmed many Philippine church records – you can search their Catalog by town or parish name to see what’s available. If the records for your ancestor’s town aren’t online, you may need to write to the local parish church or diocesan archive. When using church books, note that surnames might appear slightly different due to Spanish spelling (e.g. Maria de la Cruz instead of Maria Dela Cruz). Also, priests sometimes recorded the Spanish province or town of origin if the person was an out-of-towner, which can help if your ancestors moved around.

- Provincial and Municipal Archives: Some older records or duplicates can be found in local civil registrar offices or provincial archives in the Philippines. For instance, municipal civil registrars may hold registers dating back to the early 1900s. In some barangays (villages), local officials kept family lists or voting registers that include names of heads of households. These can be hard to access without visiting in person, but they are worth exploring if you’re able to go to your ancestral town.

- National Archives of the Philippines (NAP): The NAP in Manila holds an enormous collection of historical documents, some of which are genealogically relevant. Their Spanish-period archives (16th–19th century) include many civil documents such as census lists (padrón or tribute lists), local town records, tax lists (cédulas), and even royal decrees. For example, NAP has copies of the 19th-century Cedulas Personales (residence tax certificates) which sometimes functioned like early IDs. They also hold notarial records and court documents that might mention individuals. If your surname was unique or your ancestors held public office, you might find them referenced in those archives. The National Archives also keeps civil records like birth, marriage, and death certificates, especially from the early to mid-1900s. Researchers can contact NAP for assistance or visit in person; they provide services to copy records for a fee and have a reference library for public use.

- Cross-Referencing Church and Civil Data: Often you will use multiple sources to piece together a family. For instance, you might have a U.S. record that says your ancestor was born in 1915 in Pangasinan. You could then obtain their Philippine birth certificate (civil record) from the town’s civil registrar or PSA. That birth certificate will confirm the parents’ names. Next, you could locate the parents’ marriage record in the church registers (say they married around 1900). That marriage record could list the groom and bride’s parents’ names, allowing you to leap back another generation. Continuing this process, you follow the paper trail further back, possibly into the 1800s using church records, then maybe into the Spanish archives if needed. This linking of U.S. and Philippine records is the heart of Filipino-American genealogy research.

Tips for Interpreting Surname Origins and Overcoming ChallengesTips for Interpreting Surname Origins and Overcoming Challenges

- Don’t Assume Spanish Surname = Spanish Blood: A very common Filipino surname like Garcia or Santos does not necessarily indicate Spanish ancestry at all – it likely came from the 1849 catalog assignment. The majority of Filipinos with Spanish last names are indigenous or mixed ancestry who simply adopted a Spanish name during colonial times. Keep this in mind when reading surname origin explanations. For instance, Santos means “saints” in Spanish, but in your family’s context it might have just been the name given to an ancestor by a colonial administrator. Conversely, some Spanish-sounding surnames in the Philippines were actually borne by Latin American or Spanish soldiers/settlers who stayed – but those are harder to prove without deep research. Treat surname origin legends (e.g. “our name is Spanish because we have a Spanish great-great-grandparent”) with healthy skepticism unless you find evidence in the records.

- Indigenous and Chinese Surnames: If your surname is one of those not of Spanish origin (often recognizable as shorter or not typical Spanish words – e.g. Lim, Tan, Gatbonton, Makapagal), understand its background. Chinese-origin surnames like Tan, Ong, Co indicate Chinese roots (Tan is often from Chen or Chan, etc.). Some indigenous names starting with Gat- (meaning "noble") or Lakan- (chieftain) suggest noble ancestry from pre-Hispanic times. These names survived the Clavería decree either by exemption or by later readoption. Researching these might require looking into oral history or local lore about the family lineage. Academic books or articles on Filipino surnames (such as works by linguist Jesus Federico Hernández, who noted Chinese and other foreign influences on Filipino surnames) can shed light on meanings. Knowing the meaning or origin of a surname can be fascinating, but remember it doesn’t by itself prove family connections.

- Spelling Variations and Old Orthography: Over centuries, name spellings can change. Spanish-era records might spell a name slightly differently than today. For example, Guillermo could be spelled Guillermo or Guilllermo (typo) or abbreviated, and Ponciano might appear as Ponziano. The Filipino language also eventually embraced more indigenous spelling in some cases (using “k” instead of Spanish “c/qu”, etc.), but surnames mostly stayed as-is. Always search for variant spellings: de la Cruz vs. De La Cruz vs. Dela Cruz; Mercado vs. Mercado (same but watch for missing accents and spacing). When records were digitized or indexed, such variations can lead to missed matches, so try searching with wildcards (e.g. “Mer*cado”). If you encounter a completely unfamiliar variant in an old document, say Carreon spelled as Carrion, consider phonetics and the possibility it’s the same family. Filipino records rarely used suffixes like Jr/Sr until more recent times, but if your family did, pay attention to those as well.

- Language of Records: Be prepared to work with records in Spanish or Tagalog (or other Philippine languages). Spanish church records use a lot of standard phrases – learning a few key terms (like nacido = born, bautizado = baptized, casado = married, hijo legítimo de = legitimate son of) will help. There are translation guides and word lists available online for Spanish genealogical records. For handwritten Spanish, you might need to familiarize yourself with old script. If needed, seek help from online genealogy forums; often, people will gladly translate a record image for you. On the U.S. side, records will be in English, but sometimes with idiosyncrasies (for instance, early 1900s census race classifications might list Filipinos as “Malayan” or “ Filipino” with varying terminology). Understanding the historical context (e.g. that “PI” meant Philippine Islands, or that Filipinos might be recorded as “Asian/other” in old documents) can clarify things.

- Navigating Middle Names and Naming Customs: As discussed, the Philippine custom of using the mother’s maiden surname as a middle name can be both a help and a source of confusion. Use it to your advantage: if you know your Lola’s (grandmother’s) middle name was Mercado, that likely was her mother’s surname – you can then look for a marriage between her father and a Ms. Mercado. But in American records, that middle name might vanish or be reduced to an initial, so you have to dig to find it. When looking at documents like U.S. marriage licenses or Social Security applications (the SS-5 form), note that they sometimes asked for parents’ names – those are great for catching the mother’s maiden name in full. Additionally, realize that Filipinos traditionally (and to this day) don’t change their maiden surname upon marriage in legal documents – a woman might be Maria Santos Cruz in her birth record and remain Maria Santos Cruz on her Philippine passport even after marriage, whereas in the U.S. she might be known socially as Maria Cruz-de la Cruz or Maria Cruz if she took her husband’s name. This means when searching Philippine records, always search under maiden names for women.

- Same Surname ≠ Same Family: In the Philippines, having the same last name as someone in the same town might mean you’re related – or it might not. The Clavería decree resulted in many unrelated families choosing the same surnames from the catalog. Common surnames like dela Cruz, Santos, Garcia, Reyes, etc., will have multiple unrelated lineages in the same province. Always verify relationships with evidence; don’t assume two people with the surname Reyes in Bulacan are blood relatives without supporting records. Conversely, some very unique surnames could indicate a family connection if found in the same region. Pay attention to clustering: if you find multiple records of people with your surname in the same town in the 1900s, chances are they’re related. You can then try to link those households via older records or oral info.

- Use of Nicknames and Second Names: Filipino culture often gives people multiple names or nicknames. Someone baptised Florentina might be called Flor, Tina, or an unrelated nickname like Babes in the family. Males named José are often nicknamed Pepe, Guadalupe might be Lupe, Francisco Jr. might be Jun. These don’t appear on official documents but can cause confusion if an oral story says “Uncle Pete” but his legal name was Pedro. When you see U.S. records, note if the person used an English nickname; they might appear in a city directory as Pete Cruz, even though his formal name was Pedro. Keep a list of all known aliases or nicknames for each person to cross-reference in searches.

- Cultural Context and Historical Events: Surname research isn’t just about names and dates – understanding history will greatly enhance your search. For example, knowing about the 1906 pensionado program (which brought Filipino students to the U.S.) might explain why a young man from your family suddenly appears in Washington D.C. in 1907. Recognizing that Filipinos in the 1920s often worked in Alaska can lead you to look at Alaskan canned salmon factory employment records for traces of your granduncle. If family lore says an ancestor “went to America with the U.S. Navy,” learn about U.S. Navy recruitment in the Philippines – indeed, many Filipinos enlisted and were stationed in U.S. bases, which is another avenue for personnel records. The more you learn about Filipino-American history, the more clues you will spot in your own family story.

- Patience with Bureaucracy and Gaps: Finally, be patient. Some Philippine records may have been damaged by wars or natural disasters (for example, many Manila civil records were destroyed during WWII). You might hit a wall if the church registers you need are missing or if the surname is very common. When official records fail, turn to alternative sources: older living relatives (even distant ones) might recall genealogical details, or tombstone inscriptions in a local cemetery in the Philippines might give you dates that no paper record has. Persistence is key – you may need to write letters to a parish priest, wait for months for a reply from a civil office, or painstakingly read Spanish cursive, but the end result of uncovering your heritage is richly rewarding.

ConclusionConclusion

Tracing Filipino-American surnames and family histories is a journey that spans continents and centuries. By understanding the history of Filipino naming – from unique indigenous practices to the sweeping Spanish surname decree and the adaptations during American rule – you’ll appreciate why your surname is what it is today.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Filipino-American SurnamesExplore more about Filipino-American Surnames

References