The French Huguenots were the Protestants of France during the early modern period. The exact origin of the term ‘Huguenot’ is not clear. Various theories have been put forward that suggest it was developed as a word to describe how Protestantism largely infiltrated France from the Swiss Confederacy in the late 1520s and 1530s. Whatever the meaning, the word became synonymous with the French Protestants during the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). The Huguenots were granted freedom of religion under the terms of the Edict of Nantes issued by King Henri IV of France in 1598. However, in 1685 King Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleau which effectively revoked the Edict of Nantes and religious tolerance for French Huguenot. This triggered a wave of Huguenot migration from France and French Huguenot communities were formed all over Western and Central Europe. They also headed overseas, playing a role in the Dutch colonization of southern Africa and forming communities in New France (Canada) and the Thirteen Colonies (United States).[1]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

French Huguenots chronology of eventsFrench Huguenots chronology of events

The Protestant Reformation began in eastern Germany in 1517 after a theologian there by the name of Martin Luther issued his Ninety-Five Theses critiquing the practice of selling Papal Indulgences for the remission of sins and other corrupt practices of the Roman Catholic Church. There had been other church reformers in various parts of Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, notably John Wycliffe in England and Jan Hus in Bohemia, modern-day Czechia, but Luther was the first to be able to exploit the new medium of moveable-type printing to disseminate his ideas. By the early 1520s Protestantism (from the verb ‘protest’) was spreading all around Germany and then entered the Swiss Confederacy and the Low Countries. By the end of the decade it had infiltrated many parts of France.[2]

Over the next thirty years the community of French Protestants grew to a very substantial size. The reformed faith was particularly popular in the south of the country near the Pyrenees, a part of France with a long history of heresy during the High Middle Ages. It also gained adherents in the port towns of western France. Tensions were brewing though between Catholics and Protestants, compounded by a crisis of kingship after King Henri II was killed because of a jousting accident in 1559. He was succeeded by his fifteen-year old son, King Francis II, who in turn died a year later, leaving his ten-year old brother as King Charles IX. Two years after that the French Wars of Religion erupted, with powerful Roman Catholic lords such as the members of the powerful House of Guise in eastern France pitting their faction against a Protestant faction that would come to be led by Gaspard de Coligny and Henri de Navarre.[3]

The French Wars of Religion would last for the remainder of the sixteenth century. The most infamous episode in them came in 1572 when Henri de Navarre’s wedding to King Charles IX’s sister, Margaret of Valois, in Paris in mid-August 1572 was closely followed by the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacres in the capital and other parts of France from the 23rd of August onwards. In these anywhere between 5,000 and 30,000 French Protestants were massacred by their Catholic countrymen. By that time the French Protestants were well known as the Huguenots, a term which entered widespread use in the course of the 1560s.[4]

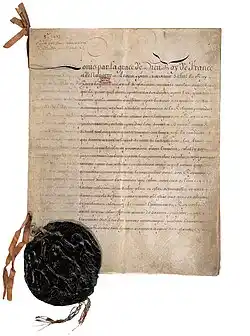

The Wars of Religion and major acts of persecution like the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre drove thousands of Huguenots out of France in the second half of the sixteenth century. However, the tensions eased at the end of the century. Following the assassination of King Henri III by a Catholic fanatic in 1589, Henri de Navarre claimed the French throne for the House of Bourbon as King Henri IV. A few years later, in order to bring the Wars of Religion to an end, he agreed to convert to Catholicism, famously stating “Paris is well worth a Mass”. In 1598 he brought the French Wars of Religion to an end by issuing the Edict of Nantes, which promised religious freedom for Protestants in France, while retaining the privileged place of Catholicism within the country.[5]

The Edict of Nantes held for nearly a century and the flow of French Huguenots out of the country that had characterized the period from the 1550s to the 1590s ended. What changed the situation was the long reign of King Louis XIV, the paragon of monarchical absolutism in early modern Europe. Louis decided over time that it was unbecoming for any French people to not follow the same religion as he did and so in 1685 he issued the Edict of Fontainebleau. This once again removed toleration of Protestantism and led to a mass exodus of Huguenots from France between 1685 and 1700, with a further steady exodus in the first decades of the eighteenth century. Eventually enforcement of the Edict of Fontainebleau died down and it was finally revoked in 1787 by King Louis XVI.[6]

Extent of French Huguenot migrationExtent of French Huguenot migration

There had been some considerable Huguenot migration during the sixteenth century before the issuance of the Edict of Nantes. A group of hundreds of French Protestants, for instance, tried to establish a colony in what is now Brazil in 1555. They called this France Antarctique, but the colony was destroyed in 1567.[7] Another expedition of French Protestants led by Jean Ribault tried to found a colony in Florida in the mid-1560s, again without lasting success. Some French Huguenots also slipped over the English Channel to southern England during the reigns of King Edward VI and Queen Elizabeth I while they were still experiencing persecution at home.[8]

The major wave of migration, however, occurred from 1685 onwards. It is estimated that 200,000 Protestants left France down to 1715. Of these approximately 50,000 migrated to England, aided by the passage of the Foreign Protestants Naturalization Act by the English Parliament in 1708. Some 10,000 headed to Ireland, settling in cities like Dublin and Cork where place-names like French Church Street and Huguenot Cemetery still attest to their impact here over three centuries ago. Others went to nearby Protestant nations, with nearly 60,000 settling in the Dutch Republic and approximately 22,000 in the Swiss Confederacy. A substantial number of French Huguenots were granted the right to settle in the Dutch Cape Colony in South Africa and others still headed directly across the Atlantic to the British Thirteen Colonies. Many settled in Upstate New York in New Paltz and New Rochelle and or on Staten Island where a community remains known to this day as Huguenot.[9]

Demographic impact of French HuguenotsDemographic impact of French Huguenots

The Huguenots amalgamated into the societies they moved to reasonably quickly. They did not continue to identify as ‘French’, particularly so as they intermarried with the people of the countries they had moved to. Thus, for example, few people will identify Winston Churchill, Britain’s wartime leader from 1940 to 1945, as anything other than ‘British’ today, though he was also a descendant of French Huguenots who settled in southern England in the late seventeenth century.[10] Perhaps the region where the Huguenots' demographic impact and genealogical imprint is greatest is in South Africa. They were a core component of the early Boer community here in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and so have contributed considerably to the development of the Afrikaner community here in modern times.[11] Given all of this, millions of people in a wide range of countries today on three continents will have a French ancestor who left France as part of the Huguenot exodus between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the French HuguenotsExplore more about the French Huguenots

- France, Vital Records Index records collection on MyHeritage

- Filae Family Trees records collection on MyHeritage

- France, Newspapers and Periodicals records collection on MyHeritage

- France, Compilation of Vital Records, 1585-1928 records collection on MyHeritage

- France, Births and Baptisms records collection on MyHeritage

- France, Church Baptisms and Civil Births records collection on MyHeritage

- France, Church Marriages and Civil Marriages records collection on MyHeritage

- South Africa, Dutch Reformed Church Registers, 1660-1970 records collection on MyHeritage

- Canada, Quebec, Marriages records collection on MyHeritage

- French Emigrants: They Were Not All Huguenots, or Nobles, or from Alsace-Lorraine at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Comment suivre un ancêtre Huguenot hors de France après 1685 at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

References

- ↑ Geoffrey Treasure, The Huguenots (Yale, 2014).

- ↑ https://www.history.com/topics/religion/martin-luther-and-the-95-theses

- ↑ https://www.worldhistory.org/French_Wars_of_Religion/

- ↑ https://www.worldhistory.org/St._Bartholomew%27s_Day_Massacre/

- ↑ N. M. Sutherland, ‘The Huguenots and the Edicts of Nantes, 1598–1629’, in Irene Scouloude (ed.), Huguenots in Britain and their French Background, 1550–1800 (London, 1987), pp. 158–174.

- ↑ https://museeprotestant.org/en/notice/the-edict-of-fontainebleau-or-the-revocation-1685/

- ↑ Charles E. Nowell, ‘The French in Sixteenth-Century Brazil’, in The Americas, Vol. 5, No. 4 (April, 1949), pp. 381–393.

- ↑ https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/huguenots-in-england/

- ↑ https://www.huguenotsociety.org.uk/history.html

- ↑ https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/The-Huguenots/

- ↑ https://www.encyclopediaofmigration.org/en/buroveafrikanci/