In order to learn How to find US ancestors' origins using US records, there are a few steps that should be followed in order to obtain results effectively. The disadvantage is that almost everyone in the USA has ancestors who came from elsewhere within recorded memory, which means that finding those ancestors’ origins is not always easy.

Note that this article deals only with ancestors who came to the US voluntarily. Ancestors who were brought to the US not of their free will present a very different set of challenges. See: Transatlantic Slave Trade

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Overall processOverall process

Broadly speaking, the goal of the process should be to ascertain the point of origin of the ancestor as precisely as possible so that further research in the foreign country is focused as much as possible. The best place to start is frequently at home. Are there heirlooms or letters belonging to that person that can lead to a home country? One possession sometimes neglected is the surname! Where does that come from? Some relatively unusual surnames have a single place of origin. It is worth searching for that surname at MyHeritage or other data aggregator and looking to see where most results come from.

When conducting this kind of research, it is advisable to consult records for siblings and/or parents of the ancestor concerned. Family members often arrived in the US at different times. So they may have different records. People arrived at different ages. So their recollections of where they were from may vary. Just as widening the number of individuals to be searched may help, increasing the number of family members involved in the search may help too. Your cousins may already know the answer to your question! And, in that regard, consider widening the number of available cousins by taking a DNA test. You may have cousins in another country entirely, with different record sets that might be helpful. It is also important to keep in mind that not all documents will apply to every time period.

Types of US recordsTypes of US records

Census entriesCensus entries

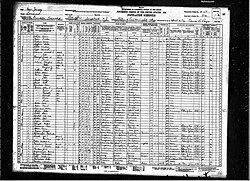

US census records from 1850 onward contain the country of birth for people born overseas. Sometimes you get lucky and the province or city is noted. Censuses for 1880-1930 also include the country of birth for each parent. Immigrants frequently lived close to other immigrants from the same area, forming a community of people who could look out for each other. So it’s often worth looking at nearby houses for other people born in a similar location. Tracking those people can yield clues to the origin of your ancestor. Some census records indicate the year of arrival (often far from accurate) and the naturalization status of the individual – see below

Vital recordsVital records

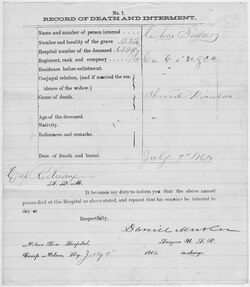

Birth certificates for some US states can contain the place of birth of both parents; if your ancestor married in the US, their marriage record might well contain their birthplace. More importantly, this vital record will likely include their parents’ names. Armed with this information, you can frequently identify the place of marriage of the parents in the home country, and hence their origin. Death certificates usually contain the age and place of birth, though the accuracy depends upon how well those living knew the deceased.

Immigration recordsImmigration records

Early passenger manifests do not include the place of origin of each passenger, though you may learn something from the origin of the relevant ship. Caution is required here, since ships leaving Hamburg, for example, frequently carried people from all over Eastern Europe. Some traveled from Eastern Europe across the North Sea to Hull, and then across England to Liverpool.

From 1906, US-bound passenger lists are full of useful information over two whole pages, including their last address, the name and address of the next of kin in the home county, the name and address of the person whom they are joining in the US and the relationship, a physical description and the village/city of the passenger’s birth. So, remember to look at page two! Investigating those US and home contacts may well reveal more about the place of origin. Many US-bound passengers came through Canada, in which case there should be an immigration record for them as they crossed into the US.

Newspaper obituaries and county historiesNewspaper obituaries and county histories

It's worth looking for in case the origin is named, though it may only be a country. County histories are particularly useful for early immigrants to rural locations because they frequently mention the origins of early settling families.

Naturalization recordsNaturalization records

Once in the US, it was normal for immigrants to naturalize, i.e., become full citizens. This required an initial petition followed by a much longer naturalization application, which will contain the date and place of birth, details of how the person entered the US, and a full list of dependents. It may also contain a photograph. Many naturalization records are not yet online. Others are online but not indexed. Often there is a card index, however, from which a case number can be obtained, which will help with a search. If you cannot find the record, it should be available via application to the local US federal court. If your ancestor had naturalized and then wanted to travel, there may be a US passport application for them, which again should contain a date and place of birth.

Social security recordsSocial security records

If your ancestor contributed to, or benefited from, US social security, which started in 1935, there will be a record of their application for a number, called Form SS-5, which will contain a person’s birth details and parents’ names. Copies are available to anyone for a fee, currently $24, as long as the subject would have been over 120 years old when application is made. For people born later, the rules are a little more complex – see link below.

Complications that can arise while searching for US ancestor's originsComplications that can arise while searching for US ancestor's origins

European borders, particularly in Eastern Europe, have changed frequently and often dramatically.[1] What was once “Austria” may today be one of a dozen countries. Such a border change may well have generated changes in the language used, a change in the name of the local town or village. A gazetteer, such as the one at JewishGen can be very useful in figuring out the modern name of a town if you know the old one, or vice versa. A Jewish person may have two names, one Hebrew and one adopted for use in their new country. They likely traveled using their original name. Names do not always transliterate easily from Cyrillic, Hebrew and many Asian languages into English. It’s worth adding too, that even if the place of origin is found, local records may have disappeared for one of a dozen reasons. Despite all this, using the combination of records above, it is usually possible to identify a birthplace.

Explore more about researching US ancestorsExplore more about researching US ancestors

- Historical records from the USA on MyHeritage

- How to Search U.S. Census Records on MyHeritage on the MyHeritage Knowledge Base

- Ask The Expert – How To Work with U.S. Census Records on the MyHeritage Knowledge Base

- The U.S. Census: Tracing Your Family in Census Records on the MyHeritage Knowledge Base

- 6 Tips for Searching Historical Records on MyHeritage on the MyHeritage Blog

- Watch Geoff Live: Adding a Census Record at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Animation: How the European Map Has Changed Over 2,400 Years - use the bar to select a year

- JewishGen

- JewishGen Communities Database - Search - excellent gazetteer of Eastern Europe

- How to Obtain a Copy of a Social Security Application Form SS-5

- Genealogy | USCIS - how to obtain US Immigration records

- Variations in Jewish Given Names - B&F

- Immigration Records | National Archives - overview of relevant US National Archives’ resources

- Internet Archive: Digital Library of Free & Borrowable Books, Movies, Music & Wayback Machine - US County Histories online

References

- ↑ This is how Europe's borders have changed over 1,000 years. World Economic Forum