Sometimes it seems like interviewing another member of your family would be a breeze, right? The fact is that getting a parent, grandparent, aunt or uncle to be interviewed is half the battle. Quite a bit of preparation is needed on your part as the interviewer and you need to have some basic skills which you’ll use during the interview if you want great results.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Getting started – checklist for interviewing family membersGetting started – checklist for interviewing family members

If you plan on interviewing family members, here are some tools, forms and procedures you may want to include:

- Determine who you want to interview, list the reasons why, and schedule possible dates and formats (in-person, video, email, etc.).

- Determine the best way to contact the interview subject. Older relatives who don’t know you personally won’t respond well to a phone call. Consider using another relative such as a cousin who knows them better to “broker” a connection and help set up the interview.

- Schedule the date and time of the interview and the location. Make sure the location is quiet and free from distractions. If it’s a long-distance interview using Zoom or Skype, the broker suggestion above might be a good idea, especially if the person being interviewed is not familiar with this technology.

- Send your invite and outline the reason for the interview and the types of questions to expect.

- Make it clear to the interview subject how the interview will be conducted and what devices you will be using. Also, elaborate on how you plan to structure the interview. For example, let your subject know that you plan to ask one question at a time and that you would like a five-minute or less response to each question.

- Manage your expectations. Reassure the person being interviewed that you are not expecting perfectly thought-out phrasing. Emphasize that you are looking for a story and pattern of speech that best reflects them and their life history.

- Check to see if you will have access to a wireless Internet connection during in-person interviews. This is important if you are using any cloud service or other platforms to upload content and want to update your online family tree in real time.

Tips and tricks for interviewing family membersTips and tricks for interviewing family members

- Be prepared. Make sure you have all your equipment and your questions or prompts. There are times when an opportunity for an interview pops up unexpectedly. Make sure you are adept at improvising; having an app on your smartphone is good insurance!

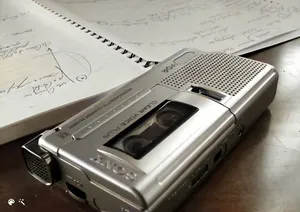

- Ask permission. Keep track of your time and if necessary, ask if you can extend the interview. If using a digital recorder or smartphone app, ask permission from the interview subject and also take time to explain the tool or the process.

- One question at a time. Don’t bunch several questions together in one long question. Short, open-ended questions asked one at a time work best.

- Fly solo (mostly). Plan on interviewing in a one-on-one format. Sometimes having others around can be inhibiting unless you are at a family gathering such as a wedding or a holiday meal. Especially when dealing with difficult topics, make sure that the interview subject is comfortable telling their story with those in the room.

- Use the grandkids. Sometimes it can be difficult to get older family members to answer questions. Consider using the grandchildren to ask the questions. No grandparent can resist telling their story to an interested child.

- Multiple interview subjects help to focus on relationships. Having two or more people as part of an interview can allow for a natural exchange of comments and those comments, in turn, give some insight into the relationship between those people.

- Use props. Photos and family mementos are great to elicit stories and bring back memories. Bring the props out one by one.

- Don’t interrupt. If inspiration strikes and you think of a good question, jot it down and save it for another part of the interview.

- Don’t challenge inaccurate information. During a response to a question, you may see that the information offered conflicts with your research or what others have offered. Don’t contradict and don’t challenge. You’ll have time to process the information and to put it into the context of your family’s history later on as you compile and prepare the contents for preservation and sharing.

- Don’t tire out your subject. Most interviews should be one hour or less in length with a max of 90 minutes. The response to each question should take about five minutes and the entire interview should last no longer than 45 minutes. In reality, the interview should stop when you first see that your subject is getting tired. Remember, you want the interview to be a positive experience and possibly lead to future interviews.

- Redirect and bring them back. Sometimes a person will go off on a tangent and speak about a topic that is not relevant. Deftly and gently bring them back around to the original question. Having the question written down and in a position where the interviewee can refer to it will also help with focus.

- Check the time. If you and your subject have agreed on a set end time, respect this and schedule another interview if necessary.

- Don’t frame the discussion. If your research shows that a person was hard to live with or perhaps had difficult relations with others, don’t offer those details in the initial question. See what the interview subject responds with and then follow up with “Well, I heard that...” or “Uncle Charles told me that...” and offer your evidence.

- Silence counts. It is fine if your interview subject is silent for a short time; recalling memories is hard work! These gaps can be edited out later on.

- Don’t interrogate. Some older relatives may not offer up names and dates in the beginning; don’t pepper them with questions. Circle back with questions such as “What was Aunt Cora’s maiden name?”

- Don’t show off. The interview is not about you and your skills. Your family member is the star so let their star shine.

- Transcribe right away. Don’t put off transcribing the oral interview if that is part of your project. Do this while the details of the interview are fresh in your mind.

- Send a thank you note. Make sure the interview subject is thanked and appreciated for their contribution. This can also ensure future interviews with the same person.

Interview questions and promptsInterview questions and prompts

- If using a release form, make sure you have hard copies and electronic copies available.

- Create a list of questions to use during the interview. Make sure you have a printed copy of the questions as well as an electronic version (PDF) on an iPad, tablet computer, or other device.

- For older interview subjects, print each question on an index card or piece of paper in a large font. Also, include a relevant image that might prompt a response.

- Consider sending the questions in advance. Some people prefer knowing the questions before the interview so that they can think about (but not rehearse) their responses.

- Don’t forget to bring old family photographs since these will often invoke memories.

- Create a master list of questions and then sort the questions into grouped themes. You may not be able to cover all questions in one interview, so use one theme for one interview, another for the next, etc.

Questions to askQuestions to ask

For many of us, the most difficult part of conducting an interview is finding the right questions to ask. Here is a selection grouped by age range of the person being interviewed and by theme. Always try to build flexibility into an interview. The “Other Memories” option at the end of each category below allows you to ask questions that pop into your mind during the interview or others that you thought of during your preparation.

Childhood Years (0-12)Childhood Years (0-12)

- Where and when were you born?

- Describe your mother and father.

- Describe your siblings, aunts, uncles, etc.

- Describe your childhood home.

- What did you like about school?

- Tell me about your friends.

- Tell me about your pets.

- Describe your early family adventures.

- What did you want to be when you grew up?

- Other childhood memories.

Teenage Years (13-19)Teenage Years (13-19)

- Describe your town.

- What did you like about school?

- Describe your best friends.

- What was a typical school day?

- What was it like to learn to drive?

- Describe yourself as a teen.

- Any extra-curricular activities?

- Describe your first job.

- Describe your grandparents.

- What historical events do you remember?

- Other teenage memories.

Adult Years (20-25)Adult Years (20-25)

- What was your first “real” job?

- How would you describe your best friends?

- Where did you live?

- Did you date/marry?

- Describe your family.

- What was your favorite saying?

- What technology did you use?

- Describe your favorite trip.

- What historical events do you remember?

- Other memories from 20-25.

Adult Years (26-40)Adult Years (26-40)

- How has your life changed?

- Describe your town and home.

- Tell me about your friends.

- Describe the most interesting place you visited.

- Describe your family.

- Any births, deaths, or additions to the family?

- What did you like to do?

- What was your favorite car? Why?

- What historical events do you remember?

- Other memories from 26-40

Adult Years (41-55)Adult Years (41-55)

- Who did you admire?

- Describe the political environment.

- Describe your family.

- What did you like to do?

- Describe your friends.

- Which vacation was the best?

- What did you do for fun?

- What do you wish you could change?

- Describe your job.

- What historical events do you remember?

- Other memories from 41 to 55

Adult (56+)Adult (56+)

- Describe your family.

- What do you like to do?

- What are your happiest moments?

- Describe a perfect day.

- Where did you live?

- What are your future plans?

- What is the future you wish for your family?

- Describe your life by decades.

- What was the best vacation you had?

- What historical events do you remember?

- Other memories from 56 onward.

PhilosophyPhilosophy

- What would you want your children to know?

- What do you believe?

- What guided your decisions?

- Describe yourself.

- Other thoughts on philosophy.

ReligionReligion

- Have your religious beliefs changed over time?

- How were you brought up?

- Other thoughts on religion.

- Other stories and songs

- What part of your life would you change?

- What got you through stressful times?

- What songs did you love (sing them)?

You can find a downloadable PDF with a comprehensive list of questions to ask family members in the Downloadable Resources section of the MyHeritage Knowledge Base.

Follow-up materialsFollow-up materials

- Send a thank you note or email or make a phone call to thank the interview subject for their time.

- If you are publishing the interview in print or some other format, consider offering the interview subject a chance to review the content first.

- Transcribe oral interviews when you have time. Consider using a program to do this or send it out to a transcribing service.

- Send a copy of the final published work to the interview subject.

PrivacyPrivacy

There are great benefits to interviewing family members as part of your genealogy research. But there is also a potential downside and dark side involving privacy and living family members. Here are some areas of concern and tips on how to proceed while still preserving and respecting a person’s right to privacy.

Published or privatePublished or private

There are ways you can still preserve your family’s stories through interviews and still ensure the privacy of those involved and the project itself. The key question is: will your final product be published in some form (video, audio, book, blog, website, or social media) or kept private?

More important is this fact: often you can’t predict what will eventually happen to the content collected. What if you start with the vision of producing a book for a family reunion but then you want to publish it online? You can’t always anticipate what will be done 5, 10, or 20 years down the road with the information. This is why asking permission up-front before interviewing a family member or collecting photos and documents is a smart move, even if you never publish the information. Most times going back to ask permission is difficult especially if the family member can’t be located or has passed away.

Document the processDocument the process

One of the best ways to protect yourself as a producer of family history content and the family members participating is to stick to the facts if you plan on publishing stories. This can often be difficult since many of the nuances of a story may have involved exaggeration and “padding” added over time. Document all stories, written and oral, as to how they were collected, and who provided the content, adding the basic “who, what, where, when” facts which are standard in journalistic reporting.

When dealing with “exaggerated stories,” use phrases such as “As it was told to me or __________ by _________...” or “The story passed down through the family states..." Also avoid adding your own opinion or view of the story.

Tips on preserving stories and protecting privacyTips on preserving stories and protecting privacy

There are ways you can still preserve your family’s stories through oral history and still ensure the privacy of those involved in the interviews and the project itself.

- A living person means a private person. Just as many family tree sites like MyHeritage will obscure certain facts about a living person when generating a report, do the same for your interview project if you contemplate some form of publication. Avoid using birth and/or marriage information or any points of data that could be used to steal a living person’s identity.

- Have interviewees sign a release form. This option seems like overkill for most of us and it probably is. But if you are organizing a large project such as a collective community memory project where participants share their memories, you might want to be safe rather than sorry. A sample release form can be found in the Resources section below which can be customized for your own project. A release form also acts as insurance, especially if you don’t yet know if you will be publishing or producing a family history that will be available to the public. It is easier to ask for a release upfront than to have to go back and try to get a release from people, especially older family members who may have passed on.

- Ask permission before using photos and recordings. Many of these items can be covered in a release form above, but make sure you have permission to duplicate photos and other materials received from family members. Also make clear how you will attribute the materials and give credit, whether the final project is published or kept private.

- Use special handling for sensitive stories. We all have what many call “black sheep ancestors” with stories that are intriguing and attractive not just to the storyteller but to the rest of the family as well. So what should you do with stories that might involve topics such as domestic violence, sexual abuse, criminal activities, and the like? Some historians opt not to share such stories if they involve living persons. But won’t the story “get lost” if it isn’t somehow preserved? One option is to produce the story in various media (digital, audio, written form) and add it to your estate planning papers. Include explicit instructions as to what should and shouldn’t be done with the information and when it can be shared and how. This way the story won’t be lost to the ages, nor will it come to light in a time that could harm living members of the family.

ConclusionConclusion

Just as the various methods used to gather and preserve family stories and oral history have evolved, so too will your approach toward this subject evolve and progress. You’ve already made a monumental step by recognizing the importance of making sure your family’s history is preserved for future generations.

- Be committed. Interviewing family members takes commitment and passion. Recognize the value of all elements and ensure that future generations will become just as excited about family history as you are now.

- Be creative. The best way to engage other family members, especially those who may not (yet) share your enthusiasm and passion, is to find new and exciting ways to share your family history.

- Be content. Know that what you are doing by interviewing family members is important. Were your family members and ancestors world-famous? Probably not. But this doesn’t mean their memories are undeserving of preservation and being passed down to future generations. Make your ancestors celebrities within your own family and be content in knowing your role in preserving their legacy.

Explore more about interviewing family members for genealogyExplore more about interviewing family members for genealogy

Getting started – a checklist for interviewingGetting started – a checklist for interviewing

- Oral History in the Digital Age - Oral History in the Digital Age

- Oral History Online – History Matters

- The Institute for Oral History - Baylor University

Interviewing family membersInterviewing family members

- Interview Release Form - Library of Congress

- How to Interview Your Relatives - MyHeritage Knowledge Base

- Interview Tips and Questions for Family Oral Histories - Family Tree Magazine

- Family Folklore: The Interview - Smithsonian Institute

- Tips For Interviewing Elderly Relatives When Researching Your Family History - Hub Pages

- Get Nosy with Aunt Rosy: Example Questions for Oral History - Genealogy.com

- How to Create an Oral Family History - AARP

- Sharing Family Traditions and Stories - PBS

QuestionsQuestions

- 25 Family History Questions You’ll Really Want to Ask- MyHeritage blog

- 50 Questions to Ask Relatives About Family History - Thought.co

- Collecting Family Stories - StoryArts

- Top 10 Tips for Interviewing Family Members - MyHeritage blog

- Downloadable Questions for Relatives printout - MyHeritage Knowledge Base

PrivacyPrivacy

- Genealogical Privacy - Facebook

Cheat sheetsCheat sheets

- Genealogy Cheat Sheets by Thomas MacEntee at Genealogy Bargains Blog