Many genealogists discover an ancestor who suddenly appears in historical records, materializing out of nowhere, leaving no hint to their origins. Another may have an ancestor who disappears without a trace, never to be found again. While alien placement or abduction may be the preferred explanation, consider an alternate hypothesis – he may have changed his name.

A name change in today’s data-driven world would almost certainly require substantial paperwork, background checks, public notice and legal proceedings. But a century or more ago, far fewer hoops were required. Under common law, one could simply begin using a new name, so long as there was no intention to defraud.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Motivations for a name changeMotivations for a name change

A person’s motivation for a name change could be many and varied. An immigrant may have wanted to assimilate into their new home, selecting a name that would be easier to pronounce or avoid prevalent anti-ethnic sentiments. An under-age person might have changed his name to enlist in the military. He may have changed it back once his service ended, or he may have kept the new name. A formerly enslaved person may have taken a new name to erase the memory of a brutal enslaver, or to honor a hero. Some formerly enslaved changed their names more than once before ultimately settling on their “final” name. Someone with a criminal past may have chosen a new name to avoid punishment.

Sometimes family reasons entered into the equation. An orphaned child might have been raised by friends or relatives and begun using their surname. It may have been an informal arrangement and not given rise to any legal paperwork. A person may have left an abusive family and adopted a new name to cut ties with their past. Or a husband and father, disenchanted with his domestic situation, may have walked out the door, and set out on a new life with a new name.

Strategies for finding the old/new nameStrategies for finding the old/new name

A name change might be as simple as a mere respelling. Examine the name you know – either the before or after name. Could other letters have made those same sounds? Laughren might have been respelled as Luffren or Lockren depending on pronunciation. For a foreign name, try to find a native speaker to determine how the name might have been spelled or pronounced. Internet resources may also be helpful. Similarly an immigrant might have chosen a translation of their name – Blanchet may have become White, or Zimmerman, Carpenter. Or perhaps they Anglicized their name – Rabinowicz to Robbins – to blend in. Sometimes, what looks like a name change might not be an intentional change at all. For example in the English-governed Ireland, the name Graham appears in the civil records for the same people identified as Grimes in Catholic Church records.

A name-changer might have selected the name of a celebrity, possibly an actor or writer, or perhaps a mother’s birth name. Whatever the motivation, a change of name can be considered a falsehood. If one is going to lie, it’s best to keep the lies as close to the truth as possible – fewer details to remember means less chance of being caught in the deceit.

Research strategiesResearch strategies

Newspapers can be a useful source. If you know the name your person died with, read every obituary. Family from his life before the name change may be mentioned. If you know the “before” name, or his parents and siblings, search for their obituaries. Even though he may have changed his name to one you haven’t yet discovered, family obituaries may clue you in on a location for him. Regardless of the reason for your research, seeking out every obituary for a person is always good practice. Newspapers from the small town where a person died, and the big city nearby may both carry the news, and include different details.

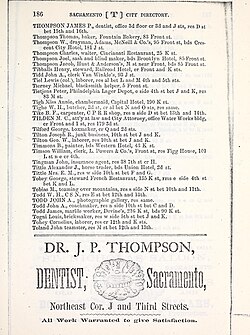

Other death records for your name-changer or his family may be helpful. Probate records for his parents may provide a specific address for him. Use city directories to see who lived at that address, and you may discover his new alias. If the name-changer died due to an accident, a coroner’s inquest or a lawsuit may provide details to merge the two identities.

Proving the link between the original and revised names may come down to commonalities in the records. While someone may have changed their name, they likely didn’t change their birthdate. Again, the fewer the inconsistencies from the truth, the less likely the fabrication would be discovered.

Follow the family. In addition to newspaper obituaries that might mention relatives or places, seek out descendants of the name-changer or his family. He may have assumed a new name, which the family may or may not have known, but descendants of his siblings may have any number of useful clues. A great-niece may remember that “Uncle Charles lived in San Francisco.” They may even have correspondence with a return address on the envelope.

Even unsourced information may provide clues. Family trees might have a death date and place for your research subject. If it looks like a “real” date, it probably is. Try to find the death index for everyone who died on that date in that place. One of those names is likely to be the alias your man reinvented for himself. The underlying death certificate for him may have the birthdate or place or parents’ or informants’ names which will help you merge the two identities.

Genetic genealogy may be helpful in identifying the “before” name. Perhaps you descend from the “after” name. If you don’t see that surname among your DNA matches, it may indicate a name change. What surnames do you see that might fill that void? Build out the trees of your matches to find your ancestor’s birth name.

Proving the name changeProving the name change

Timelines are a useful tool in documenting a name change. Include every record you find with the before and after names, detailing the date and place. You may find the different names are location-based, with the original name used in the records of the place where he started from, and the revised name in his new location. Your timeline may point to a date of the name change. Ask yourself, “Why that date?” Perhaps newspapers or other sources will suggest he ran afoul of the law and changed his name to disappear.

As hard as you worked to come up with the new name, try to disprove your theory. Is it possible that what you thought was one man with two different names is really two different men? City directories, voting registers, censuses, and other records should be checked to confirm your hypothesis and rule out the separate men scenario.

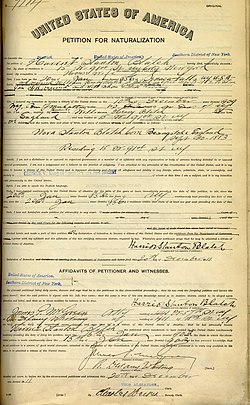

While it may seem unlikely that your ancestor took the trouble to legally change his name, it is worth looking in court records in the places he lived just in case he did. You mvay find the change in civil court records, or in naturalization documents of your immigrant ancestor.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about name-changing ancestorsExplore more about name-changing ancestors

- Flying Under the Radar – Discovering Charles Olin’s Alias by Mary Kircher Roddy, CG on Legacy Family Tree Webinars - This case study shows how to apply the strategy outlined in this how-to guide for finding an ancestor who changed his name.

- Following Your Family's Immigration Trail, webinar by Mike Mansfield on Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Ellis Island: Was Your Name Changed? from the MyHeritage Blog

References

This article was adapted from Not Who He Once Was: Tips for Finding Your Name-Changing Ancestor, a webinar presented by Mary Kircher Roddy, CG on Mar 12, 2020. Watch the full webinar on Legacy Family Tree Webinars.