The Hundred Years’ War was a conflict which was actually fought for a period of 116 years between the crowns of England and France between 1337 and 1453. The war was also not fought continuously, instead fluctuating between periods of extensive conflict and tenuous efforts at peace settlements. Conflict erupted in 1337 over efforts by King Edward III of England, who also held extensive territories around the Duchy of Aquitaine in western France, to claim the crown of France from King Philip VI. The war which followed went through periods of English victories and annexation of territory in France, notably in the 1340s and 1350s and again in the 1410s, to other periods of French buoyancy. Eventually the wars petered out in the 1450s after England had lost virtually all of its French territories, some small enclaves in the north around Calais excluded, and as the Wars of the Roses brought civil war to England. The Hundred Years’ War is associated with some migration, though as with any conflict of the late medieval period the scale of this is difficult to determine owing to a lack of precise demographic records.[1]

Hundred Years' War chronology of eventsHundred Years' War chronology of events

In 1066 William, Duke of Normandy, crossed the English Channel from his patrimony in northern France and began the conquest of England. In doing so he created a cross-Channel interest. By the 1070s he was at once King of England in Britain, but also Duke of Normandy in France. Moreover, he and his successors in the twelfth century expanded their French territories in the north and west of France, notably acquiring the Duchy of Aquitaine. What this meant was that the King of England was also one of the leading nobles of France, though one who also owed allegiance to the King of France as his liege lord.[2]

This complicated situation was nearly rendered much simpler in the thirteenth century as weak English monarchs such as King John I lost most of their French territories to the French crown in a series of wars. However, after he achieved his majority and began to rule in his own right in the early 1330s, King Edward III of England began reconsidering his claims to the French throne. The Capetian dynasty there had died out in 1328 with the death of Charles IV. He was succeeded by Philip VI who initiated the new Valois dynasty of France. Edward was only a teenager of fifteen years at the time and in no position to press his own claim to succeed Charles IV, who had been Edward’s uncle. In 1337, now a man of 24 years, Edward pressed his claim to the French throne when war erupted with France. In doing so he triggered 116 years of war between England and France. While this was ostensibly over the English royal family’s claim to the crown of France, it devolved quickly into efforts by England to reclaim the territories in northern France, in particular around Normandy, which had been lost in the thirteenth century.[3]

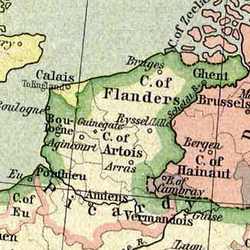

The war went through many peaks and valleys for both sides. With victories in the battles of Crécy and Calais in 1346 and 1347 Edward was in a triumphant position, but the arrival of the bubonic plague to France and England at this time broke his momentum. Nevertheless, through the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360, Edward obtained large territories across northern and western France, including Calais, Ponthieu, Gascony, Poitou and Saintogne. It was a short-lived peace and war commenced again during the 1360s.[4]

The fighting ebbed and flowed over the decades that followed. England only came close to major victory again on one occasion. This was following King Henry V’s famous victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.[5] In the aftermath of this Henry secured recognition as the heir to the French throne, but his premature death in 1422, combined with the accession of the mentally unstable Henry VI and the rise of Joan of Arc as a military leader of France, ushered in the last period of the war in which the French inflicted a series of defeats on the English and conquered their remaining continental territories except the port of Calais.[6] The war is generally understood to have come to a final conclusion in 1453 after French victory at the Battle of Castillon, although King Henry VIII attempted to revive it in the first half of the sixteenth century, conquering the city of Boulogne from the French in northern France for a brief time in the 1540s. Calais, England’s last territory in France, was finally ceded in 1558.[7]

Extent of migration during and after the Hundred Years' WarExtent of migration during and after the Hundred Years' War

While the Hundred Years’ War was a major conflict which defined much of the history of Western Europe during the late medieval period, eventually dragging in other European powers such as Castile, Navarre and Portugal in Iberia, Scotland and several powers in the Low Countries such as Flanders and Hainaut, it did not see massive migration. This was owing to the limited nature of warfare at the time, with conflict largely restricted to armies of a few thousand knights and auxiliaries clashing. As such, there was not massive dislocation of civilian populations such as has occurred in more modern times when wars are waged between major nation states. This aside, there was some migration over time across varying parts of France as different territories fell under English or French rule from period to period of the wars. This would have been in the thousands rather than the hundreds of thousands, but it was still notable.[8]

Demographic impact of the Hundred Years' WarDemographic impact of the Hundred Years' War

The demographic impact of the war would have been felt most keenly in northern and western France where the fighting was most intense and where territory changed hands on many occasions. Perhaps the most important area in this respect was the port towns of northern France in the English Channel. As cities like Calais, Boulogne and Le Havre changed hands English administrators and garrisons of soldiers would have arrived or indeed departed at various times, necessarily changing the demography of these. Early on in the conflict the differences wouldn’t have been very acute, in large part because many English administrators and officials would have spoken French and been partly Francophone in their culture owing to the legacy of Norman rule in England. However, by the fifteenth century English was spoken in some of these regions and some of the inhabitants would have identified as ‘English’ rather than ‘French’. The most acute example is Calais, which by the sixteenth century, as the last legacy of England’s involvement in France, was very much an English town, one which had to adjust to becoming part of France politically and socially after 1558.[9]

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the Hundred Years' WarExplore more about the Hundred Years' War

- Filae Family Trees record collection on MyHeritage

- Finding Your Medieval Roots: Five Simple Tips at the MyHeritage blog

- The Hundred Years' War at World History Encyclopedia

References

- ↑ https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/hundred-years-war

- ↑ https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/dover-castle/history-and-stories/angevin-empire/

- ↑ https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Hundred-Years-War-Edwardian-Phase/

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/hundred_years_war_01.shtml

- ↑ https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095931304

- ↑ https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Hundred-Years-War-Lancastrian-Phase/

- ↑ https://academic.oup.com/past/article/233/1/13/2915148

- ↑ M. M. Postan, ‘Some Social Consequences of the Hundred Years’ War’, in The Economic History Review, Vol. 12, No. 1/2 (1942), pp. 1–12.

- ↑ Susan Rose, Calais: An English Town in France, 1347–1558 (Woodbridge, 2008).