Irish genealogy can be rewarding but complex. Successful research of Irish-American surnames requires combining U.S. records (to trace immigrant ancestors and gather clues) with Irish records (to pinpoint origins in Ireland). This article outlines strategies from colonial times through the 20th century, using both online and offline methods. A variety of sources are covered including U.S. immigration, naturalization, census, church, military, and vital records, as well as key Irish sources like parish registers, Griffith’s Valuation, Tithe Applotment Books, civil records, and land records. Topics include how to handle surname spelling variations and Anglicization, use surname dictionaries and etymology tools, and incorporate DNA testing alongside traditional research.

Understanding Irish Immigration Waves and Historical ContextUnderstanding Irish Immigration Waves and Historical Context

Irish immigration to America occurred in several distinct waves, each affecting what records are available. In colonial times (1700s), one of the first major groups were the Scots-Irish (Scotch-Irish)—descendants of Scottish Lowlanders who had settled in Ulster (Northern Ireland) in the 1600s and later moved to America. Many Scots-Irish arrived in the 1700s and settled in the Appalachian regions from Pennsylvania south to Georgia. These early immigrants often came before official passenger lists, so records of them may be found in colonial church registers, land grants, or militia rolls rather than immigration manifests.

The 19th century saw a massive wave of Irish immigration, especially during and after the Great Famine (1845–1849). Millions of Irish fled starvation; a large number entered through ports like New York (e.g. Castle Garden and later Ellis Island) and Boston. By 2019, over 30 million U.S. residents claimed Irish ancestry (about six times Ireland’s current population) —a testament to this 19th-century influx. Post-famine immigrants often settled in urban centers of the Northeast and Midwest (e.g. New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago) as well as in Canada and Australia. Later, in the early 20th century, another surge occurred around 1900–1920, including those escaping economic hardship or seeking opportunity; many of these entered via Ellis Island. Knowing when your Irish ancestors immigrated (colonial era vs. 1840s vs. 1900s) will guide you to the right records and strategies.

Historical context is crucial: for example, an ancestor who immigrated in 1740 will require different research methods than one who arrived in 1840 or 1940. Colonial-era Irish (often Protestant Scots-Irish) might not be labeled “Irish” in early records and may appear in local colonial documents. Famine-era immigrants might show up in specialized sources like famine passenger compilations or in the Emigrant Savings Bank records (for New York City immigrants in the 1850s) which recorded detailed family information. Early 20th-century immigrants benefited from more standardized records (Ellis Island passenger lists with hometowns, and post-1906 naturalization papers listing birthplaces). Begin by estimating your ancestor’s immigration period – this will help target the right archives and documents.

Step 1: Gather Information from U.S. Records (Immigrant to 20th Century)Step 1: Gather Information from U.S. Records (Immigrant to 20th Century)

The first major step in Irish surname research is to trace your immigrant ancestor in U.S. records. This establishes the link back to Ireland and often provides the clues (names, dates, places) needed to search Irish archives. Start with what you know and work backwards systematically. Collecting as many details as possible about your Irish-born ancestor’s life in America will greatly increase your chances of identifying their origin in Ireland. In particular, try to learn exact names (and name variants), approximate birth dates, immigration dates, family members, and any known places in Ireland. Even a small clue like a county name on a death record or an obituary stating “native of County Cork” can break open the case. Below are key U.S. sources to utilize:

U.S. Federal and State Census RecordsU.S. Federal and State Census Records

Census records are a cornerstone of American genealogy and often the easiest starting point. Federal censuses (taken every 10 years) can confirm that your ancestor was Irish-born and provide other valuable details. For example, the 1850 and later censuses list each person’s place of birth (e.g. “Ireland”), and later censuses add more data: the 1880 census includes parents’ birthplaces, and the 1900 and 1910 censuses list the year of immigration and whether naturalized. By tracing an immigrant through the censuses, you can estimate their arrival and see their household composition over time. Tip: If you find an elderly Irish-born person living with a younger relative, that younger person might be a child who immigrated with them or was born in the U.S., giving more leads.

Don’t forget state censuses where available (e.g. New York 1855, 1865, etc., or Iowa, Kansas, and other states in various years). They sometimes asked similar questions about nativity and can fill gaps between federal censuses.

Vital Records (Birth, Marriage, Death) and ObituariesVital Records (Birth, Marriage, Death) and Obituaries

Vital records in the U.S. – civil registrations of births, marriages, and deaths – are fundamental for building your family tree and often contain direct evidence of Irish origins. A death certificate, for instance, may list the deceased’s place of birth (sometimes just “Ireland,” but in fortunate cases a county or town) and parents’ names (which you can then seek in Irish records). Marriage records can list parents and birthplaces; draft registration cards (e.g. World War I Draft in 1917–18) often ask for place of birth (occasionally listing a town or “County ____, Ireland”). If your Irish ancestor lived into the era of state vital records (generally late 19th century forward in most states), obtaining these documents is a must.

Church records in the U.S. also play a role, especially for periods or places where civil vital records were not yet mandated. Many Irish immigrants were Catholic, so Catholic parish registers in the U.S. (baptisms, marriages, burials) can be goldmines. These might mention specific birthplaces or at least give maiden names and sponsors/witnesses (who could be relatives or fellow Irish from the same area). Some archdioceses have put church record indexes online (for example, the Archdiocese of Boston and New York records are indexed on sites like Findmypast). If your ancestor settled in a big city, check if local church archives or genealogy societies have transcriptions of early Irish parish registers.

Obituaries and cemetery records are another rich source. An obituary in an Irish-American newspaper or local paper might state something like “native of County Mayo” or “born in Ballymote, Co. Sligo” – invaluable clues to pinpoint the Irish hometown. Tombstones sometimes list the county or town of origin in Ireland (e.g. “John Kelly, native of Cork, Ireland, died 1888…”). Irish immigrants often formed burial societies or were interred in Catholic cemeteries; published tombstone transcripts or cemetery registers can be found through historical societies. Always search local newspapers for death notices and “Card of Thanks” notices, as these might mention extended family (siblings, cousins) who could provide more hints about the Irish home.

Immigration and Passenger ListsImmigration and Passenger Lists

Immigration records will document your ancestor’s journey to America. The content and availability of these records depend on the time period:

- Colonial and Early America (pre-1820): Formal passenger lists were not required, so you must rely on secondary sources. Look for published compilations of immigrants (for example, some 18th-century ship passenger lists were reconstructed from letters or port records), or evidence in land records (some colonies gave land bounties for immigrants). Scots-Irish who arrived in colonial times might be noted in port arrival reports in newspapers or in indentured servant contracts. Also check revolutionary-era military records or naturalizations in colonial courts for Irish names.

- 1820–1891: The U.S. began requiring passenger lists in 1820. These early lists (available at National Archives and on genealogy websites) usually show name, age, sex, occupation, and country of origin (or “native country”). They generally do not list the exact place of origin – typically just “Ireland” for Irish passengers – especially before the 1880s. Still, finding your ancestor’s arrival can confirm their date of entry and traveling family members. For common surnames, pay attention to traveling companions or neighbors on the list who might be from the same village. Some compilations are extremely useful: for example, Michael Tepper’s book Passengers from Ireland: Lists of Passengers Arriving at American Ports 1811–1817 and David Dobson’s works on 18th-century Ulster emigrants. There is also The Famine Immigrants series, listing Irish who arrived at New York during 1846–1851. These can save time by indexing immigrants during peak years.

- 1892–1950s: Ellis Island opened in 1892 as the federal immigration station. Passenger manifests in this era are more detailed. By the early 20th century, manifests list an immigrant’s last residence and their place of birth or nearest relative in the country they came from. For example, a 1910 manifest might say an immigrant’s father is “John McMahon of Ballycastle, Co. Mayo” – a direct lead to the hometown. If your ancestor arrived through Ellis Island (1892–1924 for peak years; records exist through 1950s), you can search those manifests online for free or via subscription sites. Don’t overlook Canadian arrival records if your Irish ancestor may have come via Canada and then to the U.S., as was common for some (there are border crossing records after 1895 that document entries from Canada to the U.S.).

Practical tips: When searching passenger lists, try variant spellings of the surname (see section on surname variants below) and consider the possibility that your ancestor traveled with siblings or parents – identifying them can confirm you have the right person. If multiple results look likely, correlate with known info (age, traveling to a specific friend’s address, etc.). You might also find clues in later records: for example, naturalization papers often ask for the arrival ship and date, which you can then use to find the manifest. Some specialized databases like the Irish Emigrant databases (e.g. The “Boston Pilot” newspaper had Missing Friends ads by immigrants searching for relatives) can indirectly hint at migration patterns.

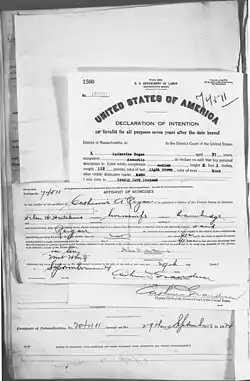

Naturalization and Citizenship RecordsNaturalization and Citizenship Records

If your Irish immigrant ancestor became a U.S. citizen, their naturalization records are critical. Naturalization papers often contain detailed personal information, especially after 1906. In the 19th century, a naturalization typically involved two steps: filing a Declaration of Intent (first papers) after a couple years of residency, and later a Petition for Naturalization (second/final papers) after five or more years. Early records (pre-1900) may be short, but usually at least name the country of origin (“Ireland”) and an oath of allegiance date. Later forms, particularly post-1906, are much more informative – they often include the exact date and place of birth in Ireland, the name of the ship and arrival port/date, and names of witnesses. After 1906, U.S. naturalizations became standardized under federal oversight. For example, a 1915 naturalization certificate file (C-File) might show “Patrick J. O’Malley, born 1 March 1888 in Clifden, Co. Galway, Ireland, arrived Boston April 1907 on SS Ivernia” – giving you a precise Irish birthplace and date to search in Irish records.

Where to find naturalization records: Before 1906, any court (city, county, state, federal) could naturalize, so you may need to check local county courthouses or state archives for those records (the National Archives (NARA) has some microfilmed copies for various courts, and many indexes are on MyHeritage). After 27 Sept 1906, naturalizations were increasingly handled in federal courts, and a copy was sent to the Immigration/Naturalization Service (now United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)). You can request post-1906 records through the USCIS Genealogy Program if you have basic details. Tip: Start by looking for naturalization indexes – many cities (e.g. New York, Boston, Chicago) have consolidated index cards for 19th-century naturalizations, which can point you to the right court and date. Also check the 1920 census: it asked citizenship status (Na = naturalized, Al = alien, Pa = first papers) and the year of naturalization – another clue when hunting for the papers.

U.S. Church Records and Community SourcesU.S. Church Records and Community Sources

Civil records only began at certain times in each state (for example, Massachusetts from 1840s, but others not until 1880s or later). For earlier periods, church records in the U.S. are vital. As noted, Irish immigrants were predominantly Roman Catholic (though Scots-Irish were often Presbyterian or Anglican). Locate the churches near where your ancestor settled and see if registers exist for the time frame. Many Catholic registers (baptisms, marriages) from the 1800s in the U.S. have been microfilmed by the FamilySearch Library or archived by diocesan archives. A baptism record for an immigrant’s child in the 1850s might list sponsors who share the surname – possibly relatives who immigrated together. Marriage records might be in Latin in Catholic registers (with Latinized names), so be aware of translations (e.g., “Jacobus” for James, “Maria” for Mary).

Beyond church registers, look for your Irish ancestors in other community records. Irish immigrant communities formed societies (like Hibernian societies, Emerald societies, Catholic benevolent organizations). Membership rolls or meeting minutes of an “Irish Benevolent Society” might list members by county of origin. Some fraternal organizations (Knights of Columbus, Ancient Order of Hibernians) kept historical rosters. If your ancestor lived in a big city, check city directories – they won’t give origin info, but they help track residence and can differentiate people of the same name.

Irish-American newspapers are an often-overlooked resource in U.S. research. Many cities had newspapers aimed at Irish immigrants, and these papers frequently published “Information Wanted” ads – essentially early social media, where immigrants placed notices seeking lost relatives or friends. These ads can be genealogical gold, as they often mention specific locales in Ireland (“John McCarthy from parish Killeedy, Co. Limerick, last heard of in New Orleans… his sister Mary seeks info”). Compilations of these ads exist, such as Irish Relatives and Friends: From “Information Wanted” Ads in the Irish-American, 1850–1871. The New York Public Library guide suggests searching their catalog or digital collections for titles like The Irish American or The Gaelic American , which can be accessed on microfilm or online. Even if your ancestor didn’t place an ad, reading those ads can give context on chain migration and common counties for immigrants in certain U.S. cities.

U.S. Military and Pension RecordsU.S. Military and Pension Records

Many Irish immigrants (or first-generation Irish Americans) served in the U.S. military, which generated records that can aid your search. The Civil War (1861–65) is particularly significant: large numbers of Irish fought for the Union (and some for the Confederacy). If your ancestor was of fighting age and in America by 1860s, check the Civil War service records and, more importantly, pension records. Union Army pension files (held at NARA in Washington, D.C.) are rich sources – veterans or their widows had to provide proof of age and identity, which for an Irish immigrant might include a statement like “John O’Brien, age 60, born in the Parish of Drumcolliher, Co. Limerick, Ireland.” Affidavits from siblings or comrades in those files sometimes mention going to school together in Ireland or other personal details. Even if the file doesn’t explicitly state the town of origin, knowing an Irish veteran’s unit could be telling (some units were Irish brigades or recruited heavily among Irish in certain cities).

Other military records: World War I Draft Registrations (1917-1918) covered virtually all men ages 18–45, including many Irish-born who had not naturalized. These cards list country of birth, and if foreign-born, often the town (because they asked for citizenship status and nearest relative – sometimes the nearest relative was a family member back in Ireland, whose address might be given). World War II Draft (1942 “Old Man’s Draft”) registered older men (up to age 64) and similarly can list place of birth. If your Irish ancestor served in earlier wars (e.g. War of 1812, Mexican War) or was in the pre-Civil War regular army, those records exist too. Bounty land applications for War of 1812 or other service may also contain personal data. Don’t overlook militia or National Guard records in the state archives.

Local Histories and Other RecordsLocal Histories and Other Records

Round out your U.S. research with local sources. County and town histories (especially those published in the late 19th century) often include biographical sketches of early settlers – if your Irish ancestor or their children were prominent locally, you might find a write-up that mentions their Irish origin. For example, a county history might say “Patrick O’Connor, born 1820 in County Clare, Ireland, came to this county in 1850…”. The accuracy can vary, but it’s a clue. Similarly, mug books, anniversary souvenir booklets of churches or fraternal societies, or even old census substitute directories (like an 1890 city directory) could have information.

At this stage, compile all the data you’ve gathered from U.S. records: full name (noting any variations used), approximate birth date, immigration year, religion (to know what church records to seek), names of relatives (spouse, siblings, parents if known), and any mention of Irish counties/towns. This dossier will prepare you for tackling Irish records. As the National Archives of Ireland advises, to successfully identify an ancestor in Irish archives you ideally need at least a surname, a location (parish or townland in Ireland), and a time period. Your U.S. research is all about finding those key details.

Summary of U.S. research: Exhaust every possible American source about your immigrant ancestor before jumping to Irish records. Many genealogists make the mistake of diving into Irish archives without a precise location or under the wrong name. The paper trail in America – from census to cemetery – will often yield the crucial info or at least narrow down the possibilities. Once you’ve gathered this, you’re ready to cross the ocean (on paper) to Ireland.

Irish surnames can be notoriously tricky due to historical anglicization (translation into English), varying spellings, and even deliberate changes. Before diving into Irish records, it’s important to understand your surname’s possible variants and how it may have changed over time:

- Gaelic Origins and Anglicization: Many Irish surnames originate from the Irish Gaelic language. When English rule expanded in Ireland (especially from the 16th–17th centuries), pressure to anglicize names increased. Gaelic “O’” and “Mac” surnames were often rendered into English phonetically or were translated. For example, Ó hUallacháin in Gaelic became O’Houlihan, but under Anglicization it might appear as Houlihan or even was translated to Holland in some cases. Another example: Ó Maoileoin was sometimes anglicized to Mallon or Muldoon, and Mac Giolla Íosa became McAleese or Gillies. Be aware that one Gaelic surname can have multiple English forms.

- Prefixes O’ and Mac: These mean “grandson/descendant of” (O’) and “son of” (Mac). Under English rule, at times, Irish were discouraged or even forbidden to use O’ or Mac prefixes (notably in the 17th century). Some families dropped the prefix entirely for several generations. By the 19th century, the usage of O’ and Mac began to rebound, especially after Irish nationalist sentiments grew. However, many Irish who emigrated in the 19th century did not use the prefixes in America, perhaps to assimilate or simply due to how their name was recorded by officials. For instance, your ancestor might be listed as “Patrick Sullivan” in U.S. records, even if the family in Ireland was known as “O’Sullivan.” When searching Irish records, try both forms (with and without O’/Mac). A surname like McGuire could be recorded as Maguire, Guire, or with a space (Mc Guire) depending on the record keeper.

- Spelling Variations: Spelling was not standardized in past centuries, and many Irish names have multiple spellings. Literacy levels in 19th-century Ireland were low, and officials or priests often wrote names as they heard them. Add in the American clerks who may not have understood Irish accents, and you get creative spellings. Phonetic variations are common: e.g., Carney vs. Kearney, Conner vs. O’Connor, Neil vs. O’Neill, Reilly vs. O’Reilly (or Riley), Mulcahy vs. Mulcahey, etc. Vowels and even consonants can shift (Donnelly vs. Donnely vs. O’Donley). Always search broadly – use wildcard characters in databases (e.g., “O’Neil*” to catch O’Neil, O’Neill, Oneill) and consider Soundex or phonetic search options. The RootsIreland.ie database, for example, has a built-in “surname variant” search that automatically checks many spelling variants in one go (searching O’Brien would also find Brien, Bryan, O’Bryan, etc.).

- Completely Different English Equivalents: A few Irish surnames were historically translated to entirely different English names. For instance, Ó Dubhghaill became Doyle, Ó Ceallaigh became Kelly, and Mac Giolla Easpaig became Gillespie. Some Gaelic surnames that resembled English words were converted: Ó Cnáimhín (meaning “descendant of Bone”) turned into Bone or Bonaventure in rare cases, and Ó Maoilmhichíl became Mulville or Milford. Use a surname reference (see next section) to learn if your surname has known alternate forms.

- First Names and Nicknames: Although our focus is surnames, remember that given names might also vary (especially relevant if searching parish registers). Patrick might be recorded as Patricius (Latin) or as “Patt” or even “Peter” in some English records (since Patrick was sometimes equated to Peter). A woman named Hanora could appear as Ann, Honora, Nora, or Norah. These first name shifts can indirectly affect your surname search – e.g. if “Nancy McGill” is actually recorded as “Anne Magill” somewhere, you need to recognize Nancy = Anne, Magill = McGill in context.

Practical strategy for surname variants: Make a list of all conceivable variants of your surname before searching Irish databases. Include versions with and without prefixes, different spellings, and even similar-sounding names. For example, for O’Shaughnessy, consider O’Shaughnessy, Shaughnessy, Shaughnessey, O’Shaughnesy, etc. If the name could have a prefix Mc/Mac or not (McCabe vs. Cabe, O’Meara vs. Meara), search both ways. If a name might be Anglicized vs. Gaelic form (e.g., Costello could appear as Ó Coisdealbha in some Irish-language contexts, though civil records would use English), be aware of both. When using online search engines like FamilySearch, use wildcard characters (* or ?) to replace unknown letters. For instance, searching “M*glin” might find Maglin, Meglin, McGlinn, etc., covering variations of McGlynn.

In summary, be flexible and creative with name spelling. Irish genealogists often say “spell it the way it sounds” – and then think of all the ways it could sound. If you don’t find your ancestor under the expected spelling, it doesn’t mean they aren’t in the records; it might mean you need to search differently. Understanding the historical forces (like English laws that led to Anglicization and dropping of O’/Mac) helps explain why your family name may appear in various guises. Once you have your list of variant spellings, you’re ready to start diving into Irish sources with a higher chance of success.

Step 3: Use Surname Dictionaries and Etymology ToolsStep 3: Use Surname Dictionaries and Etymology Tools

To deepen your understanding of your Irish surname and guide your research, it’s highly recommended to consult surname dictionaries, etymology references, and distribution tools. These resources can tell you where in Ireland a surname was historically found, its original meaning, and known variant forms. This background can help focus your search on the right region of Ireland and avoid false leads. Here’s how to leverage these tools:

- Irish Surname Dictionaries: One of the classic resources is Edward MacLysaght’s The Surnames of Ireland, which provides origins and brief histories for thousands of Irish surnames. For example, MacLysaght might tell you that Murphy comes from Ó Murchadha meaning “descendant of Murchadh,” and that it’s most common in Cork and Wexford. Another valuable work is Robert E. Matheson’s Special Report on Surnames in Ireland (1901), which includes lists of surname variants and the number of births of each surname in 1890 by county (Microsoft Word - IrelandResearchOutline). This can be useful to see which counties had a high concentration of your name around the time many immigrants left (e.g., if your surname was largely found in one province, that narrows your search). There are also modern compilations, like the Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland (2016), which covers Irish surnames in depth; check if your library can give you access to this authoritative resource.

- Online Surname Databases: Several websites offer surname origin information. For Irish names specifically, the Irish Genealogy Toolkit site has a Names section. The Library of Congress guide to Irish genealogy suggests exploring handbooks and name guides. Additionally, commercial sites have a surname lookup feature that gives meanings and geographic distributions (though often sourced from older dictionaries). Ensure you cross-reference any info you find with a reputable source, as surname lore can sometimes be muddled online.

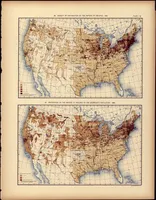

- Surname Distribution Maps: Mapping where a surname occurs can help identify an ancestor’s place of origin. In Ireland, two mid-19th-century sources serve as a surrogate “census” of surnames: Griffith’s Valuation (1847–1864) and the earlier Tithe Applotment Books (1820s–1830s). These land and tax records list heads of household and can be searched by surname to see where that name appears. You can literally create a surname distribution map by noting the counties or parishes with occurrences. For instance, if you search Griffith’s Valuation for McMorris, you might find only 36 entries nationwide, clustered heavily in County Tyrone (parish of Donaghedy) – a strong indicator that your McMorris ancestors likely came from that area. On the other hand, a search for a common name like Brennan yields 6,700 matches spread all over, so you’d need additional info (like a first name or a specific county) to narrow it down. A great tool for this is the website of Irish genealogist John Grenham (formerly associated with the Irish Times), which has an Irish Ancestors search. There, a surname search will produce a map showing the number of households with that name in each county in Griffith’s Valuation and in the 1901 census. It may also list the top parishes for the name. (The site allows a few free searches before requiring a subscription.) This visual can quickly highlight a potential home region. Example: Searching “O’Keeffe” might show heavy presence in Cork and Kerry, whereas “O’Shaughnessy” clusters in Galway and Clare. Knowing this, if your U.S. documents only said “Ireland” for birthplace, you now have an educated guess as to which county to investigate first.

- Surname Maps and Geography: You can also manually map names using free data. The Griffith’s Valuation is available for free on the “Ask About Ireland” website; you can input a surname and get a list of occurrences by county, barony, parish, etc. Consider also the 1901 and 1911 Irish censuses (free on the National Archives of Ireland site) – if your ancestor’s siblings or cousins remained in Ireland, you might find people with the same surname in certain townlands then, which could confirm the family’s home area. Another interesting source: the Matheson report of 1890 births (mentioned above) essentially gives a distribution of surnames by province – e.g. Matheson found that 544 births of “Kelly” were registered in 1890, spread across many counties but most in Connacht and Leinster. Such data (published in 1901) can be found via the Ulster Historical Foundation or other reprints.

- Etymology and Meaning: Understanding the meaning of a surname can sometimes hint at its origin. Irish surnames often derive from either an ancestor’s first name (patronymic) or a characteristic. For example, “MacDonnell” means “son of Domhnall,” indicating it started as a patronymic; “Ó Dubhghaill” (Doyle) literally means “descendant of the dark stranger,” which originally may have referred to Vikings. While the meaning might not directly help you find records, it’s part of the story of the name and could explain variant forms (like why Fitzgerald has “Fitz,” from fils meaning “son” in Norman French, used by Norman families assimilated into Ireland). Some surnames incorporate place names or clan names – for instance, MacClancy (son of the Glancy) was a notable Thomond (Co. Clare) family, and O’Mahony is strongly tied to west Cork (descendants of Mathghamhain, a king of that area). If a dictionary tells you a surname is “chiefly found in County X and originated there,” it steers your research to County X’s records.

- Surname Variant Lists: Besides dictionaries, you might find published lists of surname synonyms. The Matheson report included a section on Varieties and Synonyms of Surnames in Ireland, showing how, for example, Callaghan had variants like Callahan, O’Callaghan, etc. Modern genealogy sites sometimes have Soundex or “fuzzy search” options – use them to catch variants you may not think of. There are also resources like the RootsIreland surname search which, as noted, allows searching all variants in one go, and it will automatically include known alternate spellings. Using these tools prevents you from missing records just because the spelling was unexpected.

In summary, do your homework on the surname itself. Think of it as armchair research before the hands-on archive research. A few hours spent with surname reference books and online tools can save you days or weeks later, by honing in on the likely origin location and alerting you to alternate name spellings. It’s an essential step, especially when dealing with common surnames where you need every clue to narrow things down. Armed with this knowledge, you’re ready to tackle the Irish records where your ancestors’ lives were recorded.

Step 4: Explore Irish Records to Trace the Surname’s OriginStep 4: Explore Irish Records to Trace the Surname’s Origin

Once you have gathered U.S. information and studied the surname’s background, it’s time to dive into Irish records. The goal here is to find your ancestor (or their family) in Ireland – connecting the dots from the person you know in America to their roots in Irish soil. Irish genealogy can be challenging due to record loss (notably the destruction of many early records in the 1922 Public Record Office fire), but there is still a wealth of sources spanning from the 1700s to 20th century. We will cover key categories: civil (vital) records, church parish registers, land and property records (like Griffith’s and Tithes), census and substitutes, and other useful archives. Both online resources and offline methods (visiting archives or ordering records) will be considered.

Before searching, use the clues you have to focus your effort: ideally, you have at least a county name or even a parish/townland from your U.S. research. If you only know “Ireland” or a broad region, start with the broader-indexed sources (civil registration or Griffith’s) to narrow it down. If you do know a specific location (say, “Kilmovee Parish, Co. Mayo”), you can go straight to records for that area.

Irish Civil Registration (Birth, Marriage, Death Records)Irish Civil Registration (Birth, Marriage, Death Records)

Civil registration is the government recording of births, marriages, and deaths. In Ireland, civil registration began in the 19th century at these times:

- Non-Catholic Marriages from 1845 (this included Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, Registry Office marriages, etc. Catholics were not included until later).

- All Births, Marriages, and Deaths from 1864 onward (this is when full civil registration started for people of all religions).

These records are absolutely vital (no pun intended) for late-19th and early-20th-century research. If your ancestor was born in Ireland after 1864, there should be a birth certificate. If they married in Ireland after 1864 (or 1845 for Protestant marriages), there will be a marriage record. If they died in Ireland after 1864, similarly a death record.

The good news is that a huge portion of Ireland’s civil records are available online for free. The Irish government’s site IrishGenealogy.ie provides access to civil record indexes and images for:

- Births from 1864 (images available for births over 100 years ago, rolling cut-off).

- Marriages from 1864 (images for marriages over 75 years ago) and Protestant marriages 1845–1863.

- Deaths from 1864 (images for deaths over 50 years ago).

This means as of 2025, you can view birth records up to 1924, marriage records up to 1949, and death records up to 1974, with some gaps (Northern Irish records post-partition 1922 are separate). The National Archives of Ireland confirms that older civil BMD records can be accessed on IrishGenealogy.ie. These records typically include exact place of event (townland or street and registration district), names of parents in birth records, ages and causes of death in death records, and fathers’ names and occupations plus residences in marriage records. For example, a marriage record might show: “21 Jan 1870 at the RC Chapel of Tralee – John Connor, full age, bachelor, Labourer, of Tralee, father: Michael Connor (farmer); and Mary O’Shea, full age, spinster, of Tralee, father: James O’Shea (labourer). Witnesses …” From this, you get the couple’s fathers’ names to further your pedigree, and confirmation of location.

How to use civil records for your search: If you know an approximate birth year and a county, try searching the birth index on IrishGenealogy.ie. If the surname is common, narrow by first name or by registration district (which correspond to areas around towns). Note that many Irish emigrants did not have their births civilly registered in the very early years (especially 1860s) due to non-compliance, but by the 1880s registration was quite thorough. If you suspect your ancestor left Ireland as a child, you might find their birth certificate and perhaps those of siblings. Marriage records are extremely useful because many Irish married just before emigrating or shortly after (some would marry in Ireland then leave). If you find a marriage in, say, 1858 (Protestant) or 1865 (Catholic) for names that match your couple, check if the ages and fathers’ names align with what you know. Death records in Ireland might be less directly useful for someone who emigrated (since they died abroad), but perhaps you are also interested in the family that stayed – a death record of a parent or sibling in Ireland can be corroborative evidence you have the right family.

For Northern Ireland (counties Antrim, Down, Armagh, Londonderry, Tyrone, Fermanagh after 1922), the civil records after partition are on a different system General Register Office of Northern Ireland (GRONI). But earlier records (pre-1922) for those areas are still on IrishGenealogy.ie as part of all-Ireland coverage up to 1921.

Accessing civil records offline: If a record you need is not online (e.g., a birth in 1930, which is too recent to be imaged online), you may need to request it from the General Register Office (GRO) of Ireland or the GRO of Northern Ireland (for NI records). The process is usually straightforward – you provide names, date, registration district, and pay a small fee for a research copy. For older records that are indexed, often you won’t need this as the image is online, but keep this in mind for completeness.

Church Parish Registers (Baptisms, Marriages, Burials)Church Parish Registers (Baptisms, Marriages, Burials)

For events before civil registration (and even alongside it), church records are the backbone of Irish genealogy. These include Roman Catholic parish registers, Church of Ireland (Anglican) parish registers, and those of other denominations (Presbyterian, Methodist, Quaker, etc.).

Roman Catholic Records: Most Irish people were Catholic, and fortunately many Catholic parish registers have survived and are accessible. The National Library of Ireland (NLI) in Dublin famously microfilmed most Catholic registers up to ~1880. These images are freely available on the NLI’s website as the Catholic Parish Registers Online. You can browse by parish and date. Additionally, major genealogy websites have indexed these. The NLI site itself doesn’t have a name index, so using an indexed source is wise unless you know the exact parish and want to browse page by page.

Catholic registers typically start later than Church of Ireland ones – many begin around 1820s-1840s, though a few go back to late 1700s (especially in urban areas). A typical Catholic baptism record will have the baby’s name, baptism date, parents’ names (often including the mother’s maiden name, which is crucial), and sponsors/godparents. Marriages will list the bride and groom and their witnesses, and sometimes residences or parents (but often not parents in older ones). Burials were less commonly kept in Catholic registers, but a few parishes have death registers.

If your ancestor emigrated during the Famine or earlier, finding their baptism or marriage in Catholic records is a primary goal. Use the location clues: if a U.S. record said “native of Parish of Drum, County Roscommon,” go to the NLI site and find the registers for Drum parish and look for the family. If you only know “Co. Roscommon,” then you might search an index for the surname across all Roscommon parishes to see if one parish has a cluster of that name. RootsIreland.ie (the subscription database run by county heritage centers) is extremely useful here: it has transcribed a huge number of Catholic (and some other) registers and allows searching by surname with various filters. It even enables searching by parish or by county and can handle wildcard searches. For example, you could search all of County Roscommon for any baptism of a child named Michael O’Connor with father John between 1830 and 1840 – a quick way to find a candidate ancestor. Keep in mind transcription errors or spelling variations (hence search variants or use wildcards). Once you find a transcription, cross-check the image (either via RootsIreland.ie or the free NLI site) to verify accuracy and see if any additional notes are in the margin (sometimes notes about a later marriage or emigration exist).

Church of Ireland Records: The Church of Ireland was the state church (Anglican) – its records often start much earlier, some in the 1600s/1700s. However, the survival is spotty. Tragically, many Church of Ireland parish registers that had been sent to the Public Record Office were destroyed in 1922. Some parish registers that stayed in local custody survive. If your ancestors were Protestant (Anglican) or you suspect an ancestor’s baptism might be recorded in a Church of Ireland register (sometimes Catholics appear in them for various reasons, like mixed marriages or if the priest’s record didn’t survive), you’ll need to do a bit more digging. The Representative Church Body Library (RCB Library) in Dublin has a detailed list of what survives for each parish. Some surviving registers are now digitized (a few on IrishGenealogy.ie for Dublin city parishes, for instance). Others might be accessible on microfilm at PRONI (for Northern Ireland parishes) or local archives. If your surname is uncommon and you’re targeting a locale, checking extant Church of Ireland registers for that area (even if your family was Catholic) can be worthwhile to ensure they weren’t recorded there by mistake or necessity.

Other Denominations: Presbyterian records are crucial for Ulster Scots/Scots-Irish families, especially in Northern Ireland. Many of these are held at PRONI in Belfast or by local congregations. Some have been copied or indexed on FamilySearch or RootsIreland.ie (depending on county). If your Irish-American family was Protestant and from Ulster, definitely look for Presbyterian baptisms and marriages. Methodists often appear in Church of Ireland records in early 1800s (as Methodism was initially a movement within the Church of England), but later had their own registers. Quakers kept excellent records (held in Dublin). Jewish and other groups had small communities with their own records (mainly in Dublin/Belfast). Tailor your search to the right religious records based on what you know of the family’s faith.

Using Parish Registers Effectively: Parish registers are usually organized by date, not name, so indexing is your friend. Once you find your target family, be sure to gather all siblings’ baptisms, not just your direct ancestor. This can provide a fuller picture of the family (and more names to potentially find in U.S. records as witnesses, etc.). It’s also a good idea to note sponsors/godparents – they were often relatives (uncles, aunts, older siblings, grandparents). For instance, if John Kelly’s baptism in 1820 has sponsor “Patrick Kelly,” that could be an older brother or uncle whose own records you might trace. In a marriage, if a witness has the same surname, likely a sibling.

One challenge is that many Irish given names have Latin or English equivalents in the registers. The Latin form will appear in Catholic registers (e.g., Jacobus = James, Gulielmus = William, Maria = Mary, Honoria = Nora or Honor). Also some names might be recorded in Irish in some cases (e.g., Máire for Mary, Eoghan for Eugene/Owen). Familiarize yourself with these so you don’t overlook a record.

Land and Property Records (Griffith’s Valuation, Tithe Applotment, Estate Papers)Land and Property Records (Griffith’s Valuation, Tithe Applotment, Estate Papers)

Land records are exceptionally important in Irish research for several reasons: they cover time periods where other records are sparse, they list heads of households (useful as a census substitute), and they can help confirm you have the right location/family even if church records are missing. The two national 19th-century land surveys have already been mentioned:

- Tithe Applotment Books (1820s–1830s): These were compiled roughly 1823–1837 to assess tithes (a tax) mostly in rural areas (for the benefit of the Church of Ireland). They list occupiers of agricultural land in each townland, often with the acreage and tithe due. Not every person is listed – typically only heads of households who farmed or held land (laborers or weavers without land might not appear). Still, they provide an early snapshot. The Tithe Books are indexed and available free on the National Archives site. If your surname appears in a given parish’s tithe book, you’ll know the family was in that area by the 1830s.

- Griffith’s Primary Valuation (1847–1864): This is the big one – a comprehensive valuation of all land and property, listing household heads, conducted county-by-county between 1847 and 1864 (published by county in various years). Griffith’s Valuation (often just called “Griffith’s”) is frequently used as the census substitute for the mid-19th century since the 1851 and earlier censuses were lost. It’s fully indexed online (the AskAboutIreland.ie site provides a free search with images of the original pages and corresponding maps). In Griffith’s, you’ll find your ancestor’s (or their family’s) name if they had a house or land. It shows the townland and parish, landlord’s name (immediate lessor), a description (house, offices, land), and the valuation. While it doesn’t give family members, it places the surname in a specific locale. If you find in Griffith’s that the only O’Mahony in County Kilkenny lived in Townland X, Parish Y, that’s a promising lead.

Using Griffith’s and Tithes together can narrow down a surname’s locale with even more confidence. Maybe a name shows up in Tithes in 1833 in Parish A, and in Griffith’s in 1850 in the same Parish A – a strong indication that Parish A is your target area. Genealogist Lisa Buckner noted that by comparing Tithes and Griffith’s data, she could narrow her family’s origins to specific parishes within a county. You can do the same: for example, suppose the Doyle family lore says “Tipperary.” Searching the Tithes might show Doyle entries in 10 different Tipperary parishes. Searching Griffith’s 20 years later might also show Doyle in those parishes, but perhaps only one parish has a townland with a first name that matches your known ancestor’s father. That parish becomes the focus.

Estate Records: Many Irish farmers were tenants on large estates owned by Anglo-Irish landlords. Estate records (rent rolls, lease agreements, tenant lists, maps, correspondence) can sometimes survive and offer details at a more personal level. These are not centralized; they may be in the National Library of Ireland, National Archives, PRONI (for Northern Irish estates), or private collections. They are an advanced source – you often need to know the estate or landlord name. If Griffith’s lists “Lord Palmerston” as the lessor of your ancestor’s townland, you might research if Lord Palmerston’s papers are archived (in his case, as a British statesman, some records might be in English archives or at PRONI if it was an Ulster estate). Estate records could show, for example, a tenant application to emigrate (some landlords assisted or paid passages during the Famine), or a list of tenants evicted, etc. This can be a goldmine but requires specific leads.

Griffith’s Revision Books (Cancellation Books): After Griffith’s Valuation, local Valuation Offices kept updating the records as properties changed hands, usually in books called revision or cancellation books. They show, line by line, the changes (often in different colored inks) when a tenant died or moved and a new name replaced them, up through the early 20th century. These are held by the Valuation Office in Dublin, and copies for Northern Ireland at PRONI. They are gradually being digitized. If you cannot find your ancestor in Griffith’s because they emigrated just before it (say left in 1846 and that area was valued in 1850), the revision book might still list their father or family, and you might see the annotation that the family name was later “struck out” in 18xx when they left. This is advanced but worth knowing.

Using Land Records as evidence: Suppose your great-grandfather’s U.S. obituary said he was from “near Dungarvan, Co. Waterford.” You search Griffith’s for his uncommon surname (say, Fennell) in County Waterford and find only a couple of entries, one in the Dungarvan registration district. That’s a strong candidate for his family. Then you check the parish registers of that area and find matching baptisms. Or conversely, if you have a baptism from an Irish parish, Griffith’s can confirm the family’s presence in that townland and may list other relatives in adjacent listings (if a unique surname, everyone with that surname in the parish might be related).

Land records also help with geography – they tie names to specific townlands and parishes, which you’ll need when searching parish records and other sources. Keep an eye out for multiple households of the same surname in one townland; they could be an extended family (e.g., a father and two sons each listed as separate occupiers).

Census Records and Census SubstitutesCensus Records and Census Substitutes

Ireland sadly has a fragmented census record history. The only complete surviving censuses are 1901 and 1911, which are both fully online and searchable for free on the National Archives of Ireland site. These are incredibly useful if your family or their relatives remained in Ireland to those dates, but for many Irish-American researchers, their ancestor left well before 1901. However, it’s still worth checking 1901/1911 for collateral relatives. For instance, if your great-grandfather emigrated in 1880, perhaps one of his siblings stayed in Ireland – finding that sibling’s household in 1901 can verify parents’ names or reveal the old homestead. You can search by surname and county, or even specific townland, to see if any of your family name were present. These censuses list each person, with age, religion, occupation, literacy, county or country of birth (handy if someone was born in America or England and moved back), and relationship to head of household.

For earlier censuses: most of the 19th-century Irish census records (1821, 1831, 1841, 1851) were destroyed, but there are remnants:

- Some fragments survived (parts of 1821 for a few counties, 1831 for Derry, 1841/51 for a few parishes, etc.). These are available on the National Archives site as well.

- Census search forms for 1841/1851: During the early 1900s, the government allowed people to use the old (then still existent) censuses to prove their age for pension applications (Old Age Pension introduced 1908 for those 70+). The applications – which have survived – include forms where a person gave their parents’ names and residence in 1841/51, and a clerk searched the census for them. The resulting “Pension Search” forms often note what was found, e.g., “1851 Census: found Patrick Flynn, 2, with father Michael Flynn (farmer) and mother Catherine, in townland X, parish Y, Co. Donegal.” These records act as abstracts of the 1851 family entry. They are indexed on sites and available at NAI. If your ancestor was old enough to be in 1841/51 and lived long enough to apply for a pension (or had a sibling who did), this could be a direct window into their family in Ireland.

- Other substitutes: Aside from Tithes and Griffith’s (already covered), consider poll tax lists, militia lists, flax grower’s list (1796), Estate censuses (some estates did their own “census” of tenants), and Absentee landlords’ rentals. There’s also the 1766 religious census (surviving bits listing heads of household by religion in some parishes) and the 1798 Rebellion claims (people who suffered losses in 1798 rebellion filed claims, sometimes with personal details). These are niche sources but can help for 18th-century traces if your family were in Ireland that far back.

Other Irish Resources (Wills, Probate, Military, Newspapers, etc.)Other Irish Resources (Wills, Probate, Military, Newspapers, etc.)

Beyond the main records above, there are several other categories to explore, especially if initial searches don’t immediately yield answers or if you want to enrich the story:

- Wills and Probate: Wills can confirm family relationships and places. In Ireland, most original wills pre-1900 were destroyed in 1922, but will indexes and some abstracts survive. The National Archives has a database of Calendars of Wills and Administrations (1858–1920) – basically summaries of who died, their occupation, date of death, and who the executor/beneficiary was. For example, “1886: Michael O’Donnell, late of Ballyhaunis, County Mayo, farmer, died 1 May 1886, administration to John O’Donnell, son.” If you know siblings or parents who stayed, check if they left a will. Some older will abstracts (early 19th century) were published or reconstructed. Also, if your ancestor’s family owned land or a business, a will might have been made. For Northern Ireland, PRONI has will images up to 1910 online. Remember that Irish living abroad sometimes had their wills proved in Ireland if they still owned property there.

- Gravestone Inscriptions: If you know the hometown, see if any graveyard transcriptions have been published for that area. Local historical societies in Ireland have often surveyed cemeteries. You might discover a family plot inscription naming children who “went to America” or other clues.

- Local Histories (Ireland): Similar to U.S. county histories, there are books on local Irish history that sometimes mention prominent families, especially in rural parishes. For instance, a parish Jubilee booklet might list families present for generations. If your surname was unique in a small area, local lore might mention them.

- Military Records (British/Irish): If an ancestor was in Ireland during British rule, they might have served in the British Army (a common career for Irish in the 19th century) or in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). The RIC service records are at the National Archives in Kew (UK) and give birth county and year of birth usually. British Army pension records (Chelsea Pensioners) may list place of birth in Ireland. For early periods, those with Irish surnames who served in forces (like soldiers who fought in the Napoleonic Wars) might appear in UK military records. Also, Irish who served in WWI – their service records, if they survived, might list next of kin in Ireland (though many WWI records were lost in the 1940 Blitz).

- Newspapers (Ireland): Irish newspapers in the 19th century sometimes have personal notices that can help, like marriage or death notices. A marriage notice from 1870 might say “Thomas O’Reilly of [town] to Mary Byrne of [town].” If you suspect a marriage but can’t find it in church records, a newspaper might mention it. Also, local newspapers sometimes reported when families emigrated (“A large party of emigrants, including so-and-so, held a farewell party...”). The Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription) or the free Chronicling Ireland site can be searched by name.

- Emigration Schemes and Poor Law records: If your ancestors left as part of an assisted emigration (some Poor Law Unions paid passage during the Famine to send the destitute abroad), there may be records in Poor Law minute books. Orphan girls sent to Australia during the 1840s Famine (Earl Grey scheme) are documented. These are specialized cases, but worth noting if relevant (for example, if family myth says an orphanage sent over an ancestor, etc.).

- Genealogical Societies and Local Heritage Centres: In Ireland, each county often has a heritage or genealogy centre (many are part of the RootsIreland.ie network). These centres may have records not yet online or local knowledge. For a fee, they sometimes do research or you can visit and use resources. Also, local genealogical societies (like the Irish Genealogical Research Society, or the Genealogical Society of Ireland) publish journals with compiled records and research tips.

- National Archives of Ireland and National Library services: Both institutions provide help to genealogists. The NAI has a free Genealogy Advisory Service where professional genealogists guide researchers – if you visit Dublin, dropping by this service can be incredibly helpful to break through a brick wall. The NLI has an extensive collection including newspapers, directories, estate papers, and genealogy manuscripts (like old compiled pedigrees). If your research leads you beyond the basics, using these archives (or their online catalogs) can open new avenues.

Use each piece of information to find the next. Sometimes it’s iterative: you might have to go back and forth. If one path fails (say, you couldn’t find the baptism), try another route (maybe the family was actually from a neighboring parish or used a different version of the name – check those land records or surname distributions again).

Throughout your Irish research, keep organized notes of sources searched and results (positive or negative). Irish place names can be confusing – ensure you note the exact townland, civil parish, and county (and if relevant, the Catholic parish, which might have a different name) of any finds. This will help avoid mixing up people from similarly named places. Also, note that many Irish people moved within Ireland too (especially for work or after marriages). If you lose track of a family in one parish, consider checking nearby parishes or towns, or if the timing suggests, check if they might have been caught in parts of the 19th-century Irish diaspora to England or Scotland (for instance, Irish went seasonally to Britain for work).

Step 5: Combine DNA Testing with Surname ResearchStep 5: Combine DNA Testing with Surname Research

In recent years, DNA testing has become a powerful complement to traditional genealogical research. For Irish-American genealogy, DNA can be particularly useful given the many record gaps and common surnames. Surname research and DNA testing together can help confirm if two families with the same surname are related, identify your ancestral lines when paper records are scarce, and even pin down a region of origin via genetic matches. Here’s how to leverage DNA in the context of Irish surnames:

- Y-DNA Surname Projects: Because Irish (and most Western) surnames traditionally pass down the male line, the Y-chromosome DNA (passed from father to son) is an excellent tool for surname studies. Many Irish clans or families now have dedicated Y-DNA projects you can join. For example, if your last name is O’Neill, there are projects collecting Y-DNA results of men with O’Neill heritage to see how they interrelate. Participating in a surname project can tell you which genetic “line” of that surname you come from. Some surnames have multiple independent origins (not all Murphys are related to each other from one single Murphy progenitor – there were many Murphy families). A Y-DNA test might show that you match a cluster of O’Neills that trace back to a specific sept (like the O’Neills of Tyrone vs O’Neills of Clare, for instance). These projects essentially create a “genetic census” of people with the surname (DNA surname projects: their value to genealogy research), grouping men by their Y-DNA signature. If you match others, you likely share a paternal ancestor; if not, you might be from a different branch. The goals of surname DNA projects often include connecting people with the same surname from around the world and identifying their place of origin in Ireland. For an Irish-American whose paper trail stops in, say, 1830 in New York with a brick-wall Irish immigrant, joining a surname project and finding you match a lineage of that surname known to be from County Mayo could point you in the right direction. As noted on the Clans of Ireland site, such projects have helped many overseas Irish descendants verify paternal ancestry and connect with relatives in Ireland. Do keep in mind Y-DNA tests are male-line only; you’d need a direct male descendant of the surname (if you’re female, this could be your brother, father, or a male cousin who carries the surname).

- Autosomal DNA (Family Finder tests): The more common consumer DNA tests (MyHeritage) are autosomal, meaning they cover all family lines. While these don’t directly tie to a surname (since you get autosomal DNA from all ancestors), they can be incredibly helpful. If you test yourself (or your oldest generation available) and get matches who have Irish ancestry, you might find shared segments that point to specific families. For example, you might discover a third cousin in Ireland through MyHeritage DNA whose family never left – and in their family tree is the sibling of your immigrant ancestor. That immediately gives you new information (their tree might have the name of the town or parents). You can use the “mirror tree” technique or clustering tools (like GEDmatch, DNA Painter, etc.) to group your matches by likely branch. If a whole cluster of your matches all have County Kerry great-grandparents, and you know nothing about your own origins, that’s a strong hint you have Kerry roots. When it comes to common surnames like Kelly or Sullivan, you might have to use more targeted approaches: look for matches that share multiple segments (indicating closer relation) and see if they have any less common surnames in their trees that align with names you’ve encountered in your document research (for instance, you notice that several of your DNA matches have ancestors with the surname Costello in East Mayo in their trees, and you also have a Costello marriage as a collateral line in your paper research – this corroboration can increase confidence in the connection).

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): This is passed from mother to child (but only daughters pass it on). It follows the maternal line. Surnames don’t follow mtDNA (since daughters historically took their husband’s surname), but mtDNA can sometimes be useful if you want to test a hypothesis that two people have the same maternal ancestor. It’s more specialized and generally less used for genealogy except in certain cases, but worth mentioning for completeness.

- Geographic DNA Projects: Apart from surname projects, there are some DNA projects organized by region (e.g., an Ulster project, or an Ireland mitochondrial DNA project). These can also provide context, but a more straightforward use for most genealogists is analyzing their matches by known geographies. For example, MyHeritage’s AutoClusters may reveal connections to specific Irish counties if enough people have family trees attached to their tests.

- Confirming Paper Research: One of the best uses of DNA is to verify the family tree you’ve constructed. Let’s say through records you tentatively conclude your ancestor John McMahon was the same John born in 1830 in a certain parish in Cavan to parents P and Q. If that’s right, you should share DNA with some descendants of P and Q’s other children. If you find through DNA matches a descendant of John’s brother who remained in Ireland, that match (assuming it’s not too distant) will boost your confidence in the connection. Conversely, if you never match anyone from that family, and the surname is not extremely rare, it might make you question if you identified the correct family or if perhaps there was an adoption or other non-paternity event.

- Finding Relatives in Ireland: Many Irish people living in Ireland are now taking DNA tests too (though the uptake is still smaller compared to the diaspora). As noted by Clans of Ireland, traditionally Irish residents didn’t test because they “know where they come from," but this is changing. If someone in the home country with your surname tests, they could be a key link. For instance, a McCabe in Cavan tests and you match – by sharing info, you might discover you share great-great-grandparents. Some communities (especially adoptees or those with unknown parentage) use DNA to solve mysteries; the same techniques can apply to finding your ancestral townland when records don’t name it.

- Ethnicity Estimates: All the major DNA companies provide “ethnicity” or biogeographical ancestry estimates (e.g. 50% Irish, 25% German, etc.). Take these with caution; they are broad and not specific enough to pinpoint county origins. Most Irish-Americans will see a high percentage “Ireland” or “Celtic” in these estimates – interesting, but not nearly as useful as working with actual cousin matches. However, some companies may assign you to a more specific Irish region based on patterns in your DNA matches. For example, “Connacht, Ireland” or “Ulster” might appear if a lot of your matches have roots there. This can sometimes hint if you have multiple Irish lines from different parts of Ireland.

Getting Started with DNA: If you haven’t already tested, consider which test to take. FamilyTreeDNA is the main provider of Y-DNA tests (and also does autosomal). MyHeritage also have sizable databases (MyHeritage is popular in Europe, so you might find more Irish or British matches there in some cases). You can test at one and upload raw data to others like GEDmatch for additional tools. If doing Y-DNA, even a 37 or 67-marker test can group you, but for deep analysis, 111 markers or the Big Y test might be needed, depending on the surname project’s recommendations.

Working with Surname Project Results: When you join a Y-DNA project, volunteer administrators (often experienced genetic genealogists) can guide you. They may tell you, for example, “You’re in Lineage II of our O’Byrne project, which is believed to descend from the Wicklow O’Byrne clan.” They might encourage certain members to take higher resolution tests or SNP tests to refine the branching. Over time, these projects sometimes succeed in identifying roughly where in Ireland each cluster of a surname likely originated, especially if they can connect it with a paper trail from at least one member.

In summary, DNA testing should be seen as an aid, not a replacement for traditional research. It can prove relationships and guide you to the right location or family, but it works best in conjunction with the paper trail. Embrace it as another tool in your toolbox. When record trails run cold (as they sometimes do in Irish genealogy), DNA might rekindle the search by connecting you with previously unknown cousins who have the missing puzzle piece (perhaps a family letter or just the memory of “great-granddad was from Kilkenny”). And even if you’re able to build your family tree through records alone, DNA can give you extra confidence in its accuracy and may connect you with kin who share your interest in family history.

Additional TipsAdditional Tips

Researching Irish-American surnames is like assembling a jigsaw puzzle with pieces scattered across two countries and centuries of history. It requires patience, thoroughness, and a bit of detective work, but as we’ve outlined, there are many resources and strategies to help you succeed. To recap the process:

- Start at Home (U.S.): Gather every detail from U.S. records about the immigrant ancestor and immediate family – names, dates, places, immigration, naturalization, etc. Use federal and state censuses, vital records, church and cemetery records, passenger lists, naturalization files, military and pension records, newspapers, and local histories. These should provide clues to the Irish origin (even if it’s just “Co. Mayo” or parents’ names).

- Understand Naming and Variations: Learn about your surname’s origins and possible variants. Check authoritative surname dictionaries. Note if the name might have had an O’ or Mac originally, and search accordingly. Use tools like RootsIreland.ie’s variant search to catch alternate spellings. Recognize that the name in America might differ from its form in Irish records (Anglicization, translation, or simplification may have occurred).

- Leverage Surname Tools: Look at surname distribution maps and databases to focus your search on likely areas in Ireland. If the surname is rare, a single county might stand out. If common, combine distribution data with what U.S. clues you have (for instance, knowing your ancestor was Catholic and from Ulster narrows some names to certain counties). Check if the surname had distinct family branches in history (clan affiliations or Norman vs Gaelic origins in different places).

- Dive into Irish Records: Using the location (or best guess) from previous steps, scour Irish civil records (via IrishGenealogy.ie) for births, marriages, or deaths that match your family. Search church parish registers – start with indexes on RootsIreland or MyHeritage, then verify against the original images on the NLI site. Use Griffith’s Valuation and Tithe Applotment to establish presence in a townland. Piece together the family from these sources: maybe you find several siblings’ baptisms and the parents’ marriage. Extend to collateral lines; trace those who stayed in Ireland forward (to 1901/1911 census or to civil death records) – their records can sometimes reference the ones who left (e.g., a gravestone “erected by so-and-so in America”).

- Use DNA and Collaboration: If you hit a brick wall, or even as parallel effort, use DNA testing (especially Y-DNA for surname line and autosomal for cousin matches) to find connections that can provide hints or confirmation (DNA surname projects: their value to genealogy research). Contact DNA matches who seem to intersect with your Irish line; politely compare family info. You might find a distant cousin who has an old letter or document with the very clue you need (this is not uncommon – e.g., “Oh yes, great-aunt said our Donnelly’s were from Pomeroy in Tyrone”). Join genealogical forums or Facebook groups for the county/parish of interest or for Irish genealogy in general – many helpful enthusiasts can guide you to local resources or even do lookups. The global Irish diaspora community is large and often collaborative.

- Consult Authoritative Repositories: Make use of major archives and libraries. The National Archives of Ireland and National Library of Ireland have online catalogs and some digitized collections (and staff who might help with specific queries). The Library of Congress and other large libraries have extensive Irish-American reference collections and might have obscure emigrant journals or regional histories. If you can, visit a Family History Center or the main Family History Library (Salt Lake City) which holds microfilms/fiche of Irish parish registers, estate papers, and more. The Library of Congress guide to Irish-American resources and various university library guides (like Boston College or St. Thomas University’s Irish research guides) list books and databases that could be useful.

- Persist and Think Laterally: If a record doesn’t exist, think of substitutes. No birth record because it was before 1864? – use a baptism. Parish baptism missing? – try siblings, or consider if the family might have lived in an adjacent parish for a time. No luck in parish registers? – perhaps the family was non-Catholic or converted; check other denominations. Can’t find them in Griffith’s? – maybe they lived with relatives or had a different name spelling; search for first names or neighbors. Surname extremely common in the area? – you must gather extra evidence to ensure you have the right family (look for an uncommon first name among the children, or a combination of husband’s and wife’s surname in marriage records, etc.).

- Document and Cite Sources: As you gather information, keep track of where each piece came from. Not only will this help you later (or others who might use your research), but it prevents confusion if you step away and return to the project. For formal genealogy, write down your sources in standard format or use software to manage your citations. This guide itself has modeled citing sources for facts we’ve mentioned (e.g., citing the National Archives of Ireland pages. Emulate that in your notes so you can always retrace steps.

- Stay Organized: Use charts or software to map out the Irish families you find. It’s easy to get lost in Patricks and Marys. A simple spreadsheet of all baptisms of interest you found, with columns for date, child, parents, parish, sponsors, etc., can reveal patterns (like recurring sponsors with a certain surname – maybe the mother’s maiden name). Timelines help too, to correlate what might have prompted migration (did the family emigrate all at once? after a parent died? during the Famine year in that locale?).

ConclusionConclusion

Embrace the journey. Irish genealogy often involves peeling back layers of history – you’ll learn about Ireland’s counties, townlands, and the social conditions your ancestors faced. It can be emotional to stand in the village your forebears left or to read a famine-era letter from a relative. Every record you uncover adds to the story of your surname and family. Even variant spellings or clues can become part of the family lore (“Our name was O’Dubhthaigh in Gaelic, which means black counselor, and it became Duffy over time”).

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Irish-American SurnamesExplore more about Irish-American Surnames

- Last name research on MyHeritage

- Ireland historical record collections on MyHeritage

- Ask About Ireland

- Clans of Ireland

- Emigrant Savings Bank Records

- General Register Office Northern Ireland (GRONI)

- Irish American Resources at the Library of Congress

- Irish Ancestors

- Irish Genealogical Research Society

- Irish Genealogical Society International

- Irish Genealogy Toolkit

- Irish Newspaper Archives

- National Archives of Ireland

- RootsIreland.ie

- The Irish In Us: A Quick Primer on Irish-American Genealogy Research

References