The modern region of Northern Ireland comprises the six counties in the Northeast of the island of Ireland. The six counties are Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone. Unlike the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland is still part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The two cities of Northern Ireland are Belfast in County Antrim and Derry/Londonderry in Country Londonderry. Northern Ireland owes its official existence to the partition of Ireland in the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921.[1] As a prelude to the Treaty negotiations, the British government passed the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This allowed for the setting up of two parliaments on the island of Ireland, one in Dublin and a separate parliament in Belfast.[2] The majority of the population of Northern Ireland at this time were Protestant Unionists who wished to retain close ties with Britain. The Northern Ireland parliament was officially opened by King George V on 22 June 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty contained an opt out for the parliament in Northern Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Treaty was officially signed on 6 December 1922, and on the following day, the Parliament of Northern Ireland resolved to exercise its right to opt out of the Free State by making an address to King George V.[3]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

History of Northern Ireland

Although Northern Ireland officially came into existence in 1921, the roots of its separate nature from the rest of Ireland can be traced back much further. Humans have lived in what is now Northern Ireland, since at least 7600 or 7900BC. One of the earliest human settlements in Ireland, the Mesolithic village of Mount Sandel, dates to this period and is located not far from the town of Coleraine in County Londonderry.[4] The Ulster Cycle of mythological tales, first written down in the 9th century, (but possibly dating hundreds of years earlier to the Iron Age in Ireland), tells the story of the warrior of Cú Chulainn and the glories of Emain Macha, located in County Armagh.[5] During the Anglo-Norman invasions of Ireland in the 12th century, most of Ulster managed to retain its independence.[6]

This independence lasted up until the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1 and the outbreak of what came to be known as the Nine Years War (1593–1603). Increasing pressure from crown officials led to a rebellion among the Gaelic chieftains in Ulster. This rebellion was led by the two most powerful Ulster lords, Hugh Roe O'Donnell and Hugh O'Neill. They sought support from the Catholic king of Spain, Philip II, who was currently at war with Protestant England. Although the rebellion enjoyed some success, putting a severe strain on English resources, they and their Spanish allies suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Kinsale, on the south coast of County Cork, in 1601. Although some fighting continued in Ulster, by 1603 many of the remaining Gaelic lords agreed terms of surrender with the English crown.[7]

A few years later, in 1607, many of the remaining Gaelic Earls decided to leave Ireland for France and Spain. This event was known as the Flight of the Earls.[8] The departure of the last remaining Gaelic resistance in Ulster paved the way for the confiscation of their lands by the government of King James I (James VI of Scotland). In order to prevent future rebellions, and reward loyal supporters from Scotland, it was decided to settle 20–30,000 Scots in Ulster. This settlement, known as the Plantation of Ulster, affected counties Armagh, Cavan, Donegal, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone. Significant migration from Scotland continued throughout the rest of the seventeenth century and even into the early eighteenth century reinforcing the Scottish tinge to the character of much of the province. In the 1650s migration to the north of Ireland was encouraged by low rents in the aftermath of a decade of warfare. In the 1670s the Covenanter disturbances in Scotland resulted in some Scots seeking refuge in Ulster.[9]

The Williamite War (1689-91) would also play a large role in establishing a distinct identity for the six counties of Ulster. After the Catholic King James II was deposed in 1688 by his daughter Mary and her husband, the Dutch Prince William of Orange (later King William III), he fled to France to seek the support of his cousin, King Louis XIV of France. While the parliaments of England and Scotland declared their support for William and Mary, the Jacobites, Catholic supporters of James, rebelled in Ireland. Ulster, with its majority Protestant population, was the exception. The walled city of Derry was besieged by Jacobite forces. However, in July 1689, Derry was relieved by ships from England that sailed up the river Foyle, breaking the Jacobite blockade of the city. The siege is still annually commemorated and is the origin of loyalist slogans such as ‘No Surrender’.[10] James II arrived in Ireland on March 12, 1689, along with French money and 6,000 troops, sent by Louis XIV of France, in a first step to recover his throne. William responded by sending his own troops to Ireland and eventually came over himself in June 1890. The conflict came to an end with two decisive battles, the first known as the Battle of the Boyne in County Meath on July 1, 1690, and the second as the Battle of Aughrim, County Limerick on July 12, 1690. These battles were a victory for William and ended any hope of James reclaiming his throne. In the aftermath James returned to France where he lived out his days.[11] Originally the Battle of Aughrim was commemorated in Northern Ireland with marches by the Orange Order. However, the change to the Gregorian Calendar led to a shift in dates, with the current marches on July 12th now a celebration of the Battle of the Boyne.[12] These events helped cement a strong Loyalist Protestant identity in what would eventually become Northern Ireland.

The aftermath of the Williamite war saw a fresh influx of thousands of Scots to the north of Ireland. The principal driving factor in this migration was the distress caused by harvest failures resulting in severe famine conditions in Scotland. It has been estimated that as many as 50,000 Scots crossed the North Channel in this decade alone, a far greater number than came to Ulster in the first four decades of the seventeenth century.[13] To this day, there is still a strong Scots identity in Northern Ireland, with the Ulster-Scots dialect being one of the main languages spoken, along with English and Gaelic Irish. These Ulster-Scots were also among some of the earliest Irish immigrants to North America.[14]

In 1801, the Act of Union was passed, which dissolved the Irish parliament and brought all Irish MPs to Westminster.[15] Throughout the 1800s, a movement emerged in some parts of Ireland to reinstate the Irish parliament, known as Home Rule. This was opposed by Unionists, particularly in Northeastern Ulster. They felt a stronger connection to Britain and that they had more influence in Westminster than they would in an Irish parliament. This was increased when Catholic emancipation was introduced for Ireland in 1829.[16] This removed many of the restrictions on Catholics, even allowing them to be elected to parliament. The growing number of Catholic MPs from Ireland led to fears among Protestant Unionists that any Irish parliament in Dublin would be dominated by a Catholic majority. They coined the slogan, “Home Rule means Rome Rule”.[17]

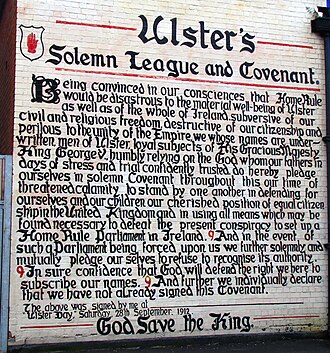

Numerous attempts at passing Home Rule were defeated by the majority Unionist House of Lords. However, changes to the legislative process in Westminster in 1911, eventually meant that legislation for Home Rule could only be delayed and not blocked completely. This meant that the introduction of Home Rule seemed inevitable. For the Unionist portion of the population prospect of Home Rule being granted was a very unwelcome development. Severing the link with Britain was seen as a threat to the religious liberty of the protestant population, and to the economic prosperity of the protestant dominated north-east of the country.[18] There had been riots and acts of protest at the time of the previous Home Rule Bills, but with the inevitable prospect of Home Rule being granted in 1914, more organised and concrete resistance was planned. In September 1912 over 200,000 men signed the Ulster Covenant pledging to fight the imposition of Home Rule in Ireland. There were even rumours that some had signed the covenant in blood.[19]

In Unionist communities across the north of Ireland small militia groups began drilling, and in January 1913 the Ulster Volunteers were formally established. The Ulster Volunteers secured a consignment of weapons from Germany, and they were landed successfully at Larne, Bangor and Donaghadee on the night of 24th/25th April 1914.[20] Despite prior knowledge of the shipment, no action was taken by the authorities. In response, Nationalists in the rest of Ireland, who supported Home Rule, set up their own militia, the Irish Volunteers.[21] They arranged to secure their own weapons, landing them at Howth, County Dublin, on July 26th, 1914.[22] Ireland briefly looked like it was on the brink of civil war between the two groups. It was only the outbreak of the First World War on 28 July 1914, that led to a temporary pause in hostilities, with many members of both Volunteer groups, enlisting in the conflict. It was hoped that fighting alongside each other in the trenches would lead to the formation of a common cause.

However, the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and the later outbreak of the Irish War of Independence from 1919-1921, would lead to an even sharper divergence between Nationalists and Unionists. While the IRA were active in Ulster during this period, they were opposed by a large Unionist majority, limiting the scope of their activity and adding a sectarian dimension to the conflict. Most areas, except Belfast and Monaghan, had no IRA brigade structure.[23] In the aftermath of the establishment of Northern Ireland, Catholic Nationalists had very little political power. Attempts at securing them greater rights through various civil rights movements, were often met by fierce backlash from groups such as the Orange Order, various Loyalist paramilitary groups and members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, the official police force for Northern Ireland. Increasing tensions between Nationalist and Unionist communities eventually erupted into a period of intense civil conflict known as the Troubles.[24] This outbreak of violence also led to the imposition of Direct Rule of Northern Ireland from Westminster in 1972.[25] From the period 1972 to 1998, it is estimated that 3,500 people were killed in the conflict, of whom 52% were civilians, 32% were members of the British security forces, and 16% were members of paramilitary groups.[26] The Troubles eventually came to an end in 1998 with the signing of the Belfast Agreement, also known as the Good Friday Agreement. One of the provisions of the Agreement was the creation of a new parliament in Northern Ireland, the Northern Ireland Assembly, governed as part of a power-sharing initiative, with the two largest political parties from both Unionist and Nationalist traditions agreeing to share power in a devolved parliament.[27]

Genealogical Research in Northern Ireland

Choosing the best sites for genealogy research in Northern Ireland is tricky because so many websites relevant to research in the Republic of Ireland are equally relevant for Northern Ireland. For example, civil records up until 1922 are freely available on Irishgenealogy.ieand many other records for Northern Ireland, including church registers and some burial records, are available on Rootsireland.ie

The General Register Office of Northern Ireland (GRONI) holds civil birth, adoption, death, marriage and civil partnership records registered in Northern Ireland. GRONI has an online database of civil registrations of births (from 1864), marriages (from 1845/1864) and deaths (from 1864) for the six counties of Northern Ireland. Please be aware that the IrishGenealogy.ie database managed by the Republic of Ireland's government also offers birth, marriage and death registrations from the counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, LondonDerry and Tyrone up to the end of 1921.

The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) is the official repository for public records for the six counties of Antrim, Armagh, LondonDerry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone. Established in 1923 following the partition of the island into the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. It is currently located in the Titanic Quarter of Belfast. It’s online collections include databases containing details of those who signed the Ulster Covenant (1912), records of pre-1840 Freeholders, street directories 1819-1900, Will calendars 1858-1965, and more than 93,000 transcribed wills. It also provides free online access to the Revision/Cancelled Books which continued the work of Griffith's Valuation from the mid 19th century to the 1930s, and an historical maps viewer.

The Ulster Historical Foundation is one of the major genealogical research agencies, family history records suppliers and education providers operating in Northern Ireland. The company is based in Newtownards, about 10 miles east of Belfast. The organisation specialises in undertaking Irish and Scots-Irish research and runs both study programmes and a membership association called the Ulster Historical and Genealogical Guild. The Ulster Historical Foundation also publishes and distributes many books of interest to Irish genealogists and historians. While many relate only to Northern Ireland, some cover the entire island.

The North of Ireland Family History Society (NIFHS) was founded in 1979 and now has worldwide membership, many branches and an excellent Research Centre. Over the years, as the interest in genealogy has grown at home and abroad, the group has expanded by creating a dozen or so other Branches in the North of Ireland to form the Society, which now has well over a thousand members including many overseas. While each Branch organises its own events, the Council of the Society has introduced a number of services for its local Branch Members and for its distant Associate Members – these include the development of an excellent Research Centre with free look up facilities for Members who cannot visit the premises, the publication of the Journal and E-Newsletter to keep Members in touch with developments and with one another, and the publication of useful research guides and the development of courses to assist Members with their research. In addition many Branch Members have transcribed a large range of records for the benefit of all Members – with the development of crowd sourcing techniques many Associate Members can now help with these transcription projects.

The Presbyterian Historical Society is located in Belfast. Founded in 1907, the object of the society is to explore and promote an understanding of the history of Presbyterianism in Ireland. This is achieved by various means, including the collection and preservation of historic materials and records of these churches. They do not provide a full genealogical research service but can offer help and advice about Presbyterian family history to both on-site visitors and to remote enquirers.

The Mellon Centre for Migration Studies is based at the Ulster American Folk Park, located just outside the town of Omagh, Co Tyrone. The Mellon Centre is a dedicated migration resource centre on the island of Ireland with specialist expertise in the story of the migration of the peoples of the island of Ireland across the globe. One of their key collections is the Irish Emigration Database (IED).[28] This is a virtual archive of original primary material which has been transcribed, digitised and is key-word searchable. The documents within IED are related to historic Irish migration to North America from 1700-1950. The complete IED is available free of charge to visitors at the Centre, at all branch libraries of Libraries NI and at the Search Room of the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI).

The Northern IrelandGenWeb Project is part of the WorldGenWeb Project and is a local resource page for Northern Irish research. The Northern IrelandGenWeb Project has been online since early 1998 and is a volunteer driven project. Each of the volunteers hosts a county that they have a research interest in. Each County page has a list of useful online resources, including lists of parishes for each county and transcripts of other useful records.

Researchers should also be aware that some records connected to Northern Ireland are still available in repositories in the Republic, such as the National Library of Ireland and the National Archives of Ireland. For example, some of the surviving 1821 census fragments for County Fermanagh and the 1851 census fragments for 1852 for County Armagh are accessible through the National Archives of Ireland census website.[29] Other records are kept in repositories such as the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

See also

Explore more about Northern Ireland

- Northern Ireland - Collection Catalog on MyHeritage

- Northern Ireland Portal on Geni

- Using Y DNA testing to investigate Ulster and Scottish surnames webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Irish ancestors – Top 5 websites you need to know about webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Who were the Scots-Irish? webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- The Scots-Irish in America webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- The Northern IrelandGenWeb Project

- The Mellon Centre for Migration Studies

- The Presbyterian Historical Society

- The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI)

- Ulster Historical Foundation

References

- ↑ https://www.nationalarchives.ie/2021commemorationprogramme/the-treaty-1921-records-from-the-archives/

- ↑ https://www.creativecentenaries.org/government_of_ireland_act

- ↑ http://www.nationalarchives.ie/topics/anglo_irish/dfaexhib2.html

- ↑ https://www.causewaycoast.guide/locations/mountsandel-fort

- ↑ https://visitarmagh.com/stories/live-our-celtic-myths-legends-in-the-ancient-site-of-navan-fort/the-ulster-cycle/

- ↑ https://www.discoveringireland.com/the-anglo-norman-conquest/

- ↑ https://www.theirishstory.com/2019/01/10/hugh-oneill-and-nine-years-war-1594-1603/

- ↑ https://www.donegalcoco.ie/media/donegalcountyc/archives/pdfs/Flight%20of%20Earls%20booklet%20PDF.pdf

- ↑ https://scottishhistorysociety.com/the-national-covenant-1637-60/

- ↑ https://www.theirishstory.com/2018/07/08/the-jacobite-williamite-war-an-overview/

- ↑ https://celt.ucc.ie//published/E703001-010/text001.html

- ↑ https://www.discoveringireland.com/the-battle-of-the-boyne/

- ↑ https://discoverulsterscots.com/history-culture/plantation-ulster-1610-1630

- ↑ https://discoverulsterscots.com/emigration-influence/america/scotch-irish-america-timeline/1600s-dawn-scotch-irish

- ↑ https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/parliamentandireland/collections/ireland/act-of-union-1800/

- ↑ https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/2015-parliament-in-the-making/get-involved1/2015-banners-exhibition/rachel-gadsden/1829-catholic-emancipation-act-gallery/

- ↑ https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/articles/home-rule-for-ireland-q-a

- ↑ https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/collections-research/art-and-industry-collections/art-industry-collections-list/easter-week/discover-the-historic-asgard-yacht/1912-1914-ireland,-the-asgard-and-the-home-rule-cr

- ↑ https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/about-ulster-covenant

- ↑ https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/larne-marks-centenary-of-uvf-gun-running-1.1775427

- ↑ https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/collections-research/art-and-industry-collections/art-industry-collections-list/easter-week/discover-the-historic-asgard-yacht/1912-1914-ireland,-the-asgard-and-the-home-rule-cr

- ↑ https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Collections-Research/Art-and-Industry-Collections/Art-Industry-Collections-List/Easter-Week/Discover-the-historic-Asgard-yacht/1914-The-Howth-Gun-Running

- ↑ https://www.museum.ie/en-ie/collections-research/collection/ulster-in-the-war-of-independence

- ↑ https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-troubles

- ↑ https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/parliamentandireland/overview/direct-rule/

- ↑ https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/sutton/tables/Status.html

- ↑ https://www.ireland.ie/en/dfa/role-policies/northern-ireland/about-the-good-friday-agreement/

- ↑ https://mellonmigrationcentre.com/about-us/irish-emigration-database-ied/

- ↑ https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/