Norwegian surnames are family names found in the territory of Norway and on a smaller scale, in the neighboring countries of Denmark and Sweden, as well as the Norwegian diaspora, which is found mostly in North America and Australia.

Like in most of Scandinavia, they were originally patronymic and similar to the surnames used in modern Iceland, consisting of the father's name and one of the suffixes -sen /-son (son) or -datter /-dotter (daughter), depending on the person's gender. Unlike modern surnames, they were specific to a person and were not transferred to a person's children.

History of Norwegian surnames and naming conventionsHistory of Norwegian surnames and naming conventions

Until the end of the Middle Ages, family names were seldom used in Norway, except by some elite families. For a long time after that, they were inconsistently used and only found in the upper classes of Norwegian society. By the beginning of the 19th century, less than 5% of the rural population in Western Norway had a hereditary surname. However, the use of hereditary surnames slowly grew in the cities since the 16th century, with around 25% of the population of Bergen using hereditary surnames by the end of the 17th century, and 40% of the city's population by the early 19th century. Before 1850, the traditional system of given names, patronymic, and farm names was the common naming convention.[1] After this, the use of hereditary surnames in the cities became more common, to the point that by 1865, most people in Trondheim had hereditary surnames, and by the beginning of the 20th century, most of the urban Norwegians had hereditary surnames, with non-hereditary patronymics often used in addition to the family name.

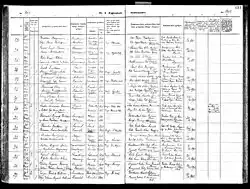

After large-scale migration from rural to urban areas in the 19th century, migrating families often adopted a non-hereditary patronymic as their family name during the move, with the use of hereditary family names becoming common in rural areas as well by the beginning of the 20th century. In rural areas, toponymic surnames were a common alternative to adopting a patronymic as the hereditary family name. In 1923, a law was passed ordering all newborn children to be assigned a hereditary family name at birth but did not force people who still did not have a family name to adopt one.[2][3] Like in all of Scandinavia (except for Sweden since the year 2000) the Lutheran Church is the official state's religion, and it controls many life-cycle aspects. This means that the records of Lutheran parishes are the first place to search when researching for a Norwegian (or Scandinavian) ancestor, as most Norwegians are Lutheran Christians. This information is accessible at the Historisk befolkningsregister (Norwegian Historic Population Register), which contains all Norwegians born before the census in 1910, with more recent records being added from other sources.

Norwegian naming conventionsNorwegian naming conventions

In the past, the usual practice was for a woman to take a man’s name when they got married. From 1923 women had to use the surname of their husbands and men couldn't use their wife's farm name, but in 1964 this was changed[4]. It’s also very common for children to take both of their parents’ surnames and decide which one to go by when they reach adulthood. If the parent's surnames aren't hyphened the last surname is considered the surname, and the other surname is a middle name. Some couples may even dig into their family histories and retrieve farm names that were lost as long as the name is used by more than 200 people. If less than 200 use a name it's protected by law, and users must apply for the name and get approval from everyone that has it.

Norwegian farm-based toponymic surnamesNorwegian farm-based toponymic surnames

Farm names are very common in Norway, as in the rest of Fennoscandia. By 1801, around 90% of the Norwegians lived on a farm;[1] today, nearly three-quarters of all Norwegian surnames originate in a farm name.[3] For centuries, it was the norm to take the name of the farm where the person lived, regardless if the person belonged to the owner's family. It is very common for Norwegians to have both a patronymic and a farm name. Farm names generally fit into one of two categories: nature-inspired and culture-inspired.

Culture-inspired names, on the other side, are derived from something to do with religion, organization in society, or even Old Norse names.[5] For example, Torshov (after the Norse god Thor), Hove (place of worship), or Onsåker (after the god Odin).

Nature-inspired Norwegian surnames, on the other side, are often the oldest farm names and the most common of farm names, with common endings such as the following:

- -berg (“hill”)

- -vik (“cove” or “creek”)

- -sand (“sand”)

- -bekk (“stream”)

- -knaus (“knoll”)

- -fjell (“mountain”)

- -heim (“home”)

- -land (“land”)

- -stad (“place”)

- -åker (“fields”)

- -gård (“farm”)

While most nature-inspired Norwegian surnames can be distinguished by a variety of endings and suffixes, some can start with particles like li- (“mountain slope”).

Norwegian non-farm toponymic surnamesNorwegian non-farm toponymic surnames

Changes in Norwegian surnames upon migrationChanges in Norwegian surnames upon migration

If a person moved from one farm to another, they generally stopped using the old farm name and took the new one, keeping their patronymic and adding the farm name as a unique family identifier. When families moved from a farm to the city during the Industrial Revolution, they generally kept the last farm name they had.

Norwegian emigrants often took the farm name with them as their permanent surname when they moved to communities that did not use patronymics. For example, a man named Lars Olsen Hagelund (Lars, son of Ole, from the farm Hagelund) might immigrate to North America and begin to call himself Lars Hagelund. In some cases, people dropped the farm name and kept their patronymic name. This is an important factor to take into account when searching for Norwegian emigrants in the U.S. and Canadian records.

Norwegian surnames are popular in certain states of the USA, like North Dakota (30% of the population are of Norwegian origin), Minnesota (17.3%), South Dakota (15.3%), Montana (10.6%), Wisconsin (8.5%), and Iowa (5.5%). In Canada, the provinces of Saskatchewan (7.6%), Alberta (4.9%), British Columbia (3.6%), and Manitoba (4.2%) have significant communities of Norwegian origin.[3]

Norwegian spelling variationsNorwegian spelling variations

Norwegian orthography has undergone significant standardization since surnames were made mandatory, with two official forms of written Norwegian coexisting today, Bokmål (literally 'book tongue'), and Nynorsk ('new Norwegian') and two non-official forms, Riksmål and Høgnorsk. This has caused toponymic surnames to be commonly spelled in different and often archaic ways, like the surnames "Wiik" and "Wiig", both common variant spellings of "Vik" with 2,459, 1,289, and 4,977 people bearing each variant of this surname in 2022, respectively. [6]

Popular Norwegian surnamesPopular Norwegian surnames

Just like in Denmark and Iceland, the top-10 popular surnames are all of patronymic origin.[7]

| # | Surname | Etymology | Bearers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hansen | son of Hans | 49,503 |

| 2 | Johansen | son of Johan | 47097 |

| 3 | Olsen | son of Ole | 46,094 |

| 4 | Larsen | son of Lars | 35,935 |

| 5 | Andersen | son of Anders | 35,277 |

| 6 | Pedersen | son of Peder | 33,467 |

| 7 | Nilsen | son of Nils | 32,620 |

| 8 | Kristiansen | son of Kristian | 22,356 |

| 9 | Karlsen | son of Karl | 20,113 |

| 10 | Johnsen | son of John | 19,718 |

Celebrities with Norwegian surnamesCelebrities with Norwegian surnames

- Leif Eriksson, Norse explorer, believed to have been the first European to have set foot on continental North America

- Kjetil André Aamodt, Norwegian alpine skier, 4-time Olympic champion

- Lance Edward Armstrong (born Gunderson), American cyclist, 7-time winner of the Tour de France

- Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, also known as the Olsen twins, US fashion designers and former actresses that debuted playing as a toddler in the sitcom "Full House".

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Norwegian surnamesExplore more about Norwegian surnames

- Last names on MyHeritage

- Historical records from Norway on MyHeritage

- Historisk befolkningsregister (Norwegian Historic Population Register)

- search for names in the Norwegian cenus SSB