The Quakers and Pennsylvania refers to the colonization of what became the state of Pennsylvania in the United States as an English colony from the early 1680s onwards. The Pennsylvania colony was originally developed by William Penn as a proprietary colony after he received an extensive grant of land here from King Charles II of England. Penn was a Quaker, a new branch of Christianity that had only first emerged in England in the 1650s. He decided to establish a religious haven for non-conforming Christians in the Americas on the lands he received, founding a new colony called Pennsylvania, effectively meaning ‘Penn’s Land’. Penn not only encouraged English Quakers and other religious non-conformists to settle in Pennsylvania, but also offered a place to continental religious radicals like the Mennonites, Moravians and Baptists, many of whom hailed from Central Europe. Hence, Pennsylvania became the home of the Quakers in America and of the German American community, with Germantown being established near Philadelphia.[1]

The Quakers and Pennsylvania chronology of eventsThe Quakers and Pennsylvania chronology of events

By the middle of the seventeenth century the eastern seaboard of North America was being extensively colonized by several European powers. The French had established a presence in several parts of what is now Canada, the Dutch had acquired New York, which they variously called New Holland (New York State) and New Amsterdam (Manhattan), while the Swedish had briefly tried to found a colony around the Delaware River and the coast of what is now New Jersey. The English were the foremost power, with thriving colonies in New England, Virginia and the Carolinas. In the mid-1660s they secured New Holland from the Dutch during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and renamed New Amsterdam as New York. It was in an effort to set up an unbroken chain of colonies between New England and the Carolinas that the crown began issuing grants to private colonists to establish proprietary colonies, ones where the chief colonist ran it initially as a private colony, to individuals like George Calvert, first Baron Baltimore, in the middle of the seventeenth century, who went on to found Maryland.[2]

The most significant of these grants of land that led to the establishment of a proprietary colony was made to William Penn by King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1681. Penn’s father had been a prominent supporter of King Charles I in the English Civil Wars of the 1640s and a noted naval commander. The crown owed him an extensive amount of back pay when he died in 1670 and so the grant of land which was made to his son, William, in 1681 was compensation for the debt.[3]

The grant of land to William Penn was unusual in many ways. Firstly, it was very extensive, comprising a significant stretch of the coastline of North America. Secondly, Penn was a Quaker and so was a religious non-conformist. Quakerism had emerged in England in the 1650s based on the teachings of George Fox. The actual name for the religion was The Religious Society of Friends, though they became known colloquially as Quakers. Fox held that people were all possessed of an ‘inner light’ and he rejected many of the basic tenets of Christianity. Quaker religious ceremonies were not really in the shape of a Mass at all, but involved people meeting to commune with one another. There were no priests or ministers or organised ceremony. Inevitably the Quakers experienced official persecution in England because of their non-conformity with the established Anglican Church. Therefore, when William Penn received his lands in 1681, he immediately set on the idea of establishing a haven for Quakers and other religious minorities in North America where they could worship in peace.[4]

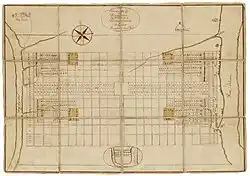

Penn acted very rapidly. In 1682 he established the city of Philadelphia (meaning ‘brotherly love’) on the banks of the Schuylkill River and began promoting his colony to not just English Quakers but other radical religious minorities across Europe such as the Moravians, Mennonites and Baptists of Central Europe. It soon began to grow and Philadelphia became the largest city of the Thirteen Colonies which emerged in North America in the early eighteenth century. The wider colony became known as Pennsylvania, meaning ‘Penn’s Land’. Penn also acquired further territory westwards, though unlike the English colonists in New England and Virginia, he attempted to do so through peaceful negotiations with the local Lenape Indians.[5]

Extent of migration to PennsylvaniaExtent of migration to Pennsylvania

Penn’s colony proved popular. By 1700 they were nearly 20,000 people living in Pennsylvania. He was able to draw on a network of contacts he had established beyond England in places like Germany and Ireland where he had spent much of the 1670s travelling before he obtained his grant of Pennsylvania. This drew many settlers from places like Germany and Bohemia, while the Quaker movement had also established substantial communities in Scotland and Wales. Thus, settlers came from places other than England to the Pennsylvania colony. By the time Penn died in 1718 the population was nearly 30,000 and there were over 10,000 alone living in Philadelphia.[6]

Demographic impact of the Quaker colony of PennsylvaniaDemographic impact of the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania

The longer term demographic impact of the movement of Quakers and other non-conformists to Pennsylvania was very substantial. In the mid-1740s, owing to continued migration from Europe and natural increase amongst the first and second generations of settlers, the population of the colony reached 100,000. It had more than doubled to above 200,000 by the time the Second Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia and then signed the Declaration of Independence there in 1776 early in the American Revolutionary War.[7] German and English Quakers and religious non-conformists from Pennsylvania like Daniel Pastorius and John Woolman were prominent early opponents of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the Quakers led the Abolition movement on both sides of the Atlantic in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[8]

Pennsylvania would remain the heartland of Quaker settlement in America into modern times, while the German American community is also very substantial here, with Germantown being a significant suburb of Philadelphia. Owing to its extensive settlement and the manner in which the Penn family expanded the colony westwards to where Pittsburgh is today, Pennsylvania is the fifth most populous state in the United States with 13 million inhabitants.[9]

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the Quakers and PennsylvaniaExplore more about the Quakers and Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania, Chester County Tax Registrations, 1715-1890 records collection on MyHeritage

- Immigration of the Irish Quakers Into Pennsylvania, 1682-1750 records collection on MyHeritage

- Pennsylvania Newspapers, 1795-2009 records collection on MyHeritage

- Pennsylvania Marriages records collection on MyHeritage

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Passenger Lists, 1800-1882 records collection on MyHeritage

- Quaker Migration into America at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Introduction to Quaker Genealogy Research at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Quaker Migration in North America Prior to the American Revolution at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Friends of Friends: Quakers and African American Communities at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

References

- ↑ https://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/pa-history/1681-1776.html

- ↑ https://www.history.com/topics/colonial-america/thirteen-colonies

- ↑ https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/october-14/

- ↑ https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/religious-society-of-friends-quakers/

- ↑ https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/pennsylvania-founding/

- ↑ https://web.viu.ca/davies/H320/population.colonies.htm

- ↑ https://web.viu.ca/davies/H320/population.colonies.htm

- ↑ https://www.quakersintheworld.org/quakers-in-action/282/Quakers-in-colonial-Pennsylvania

- ↑ https://data.census.gov/profile/Pennsylvania?g=040XX00US42