Basque emigration or Basque diaspora refers to the process through which people with Basque origins have moved to other parts of the world. This article will explore Basque migrations across the centuries and current concepts of Basque diaspora in different countries.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

History of Basque emigrationHistory of Basque emigration

Basque people origins are uncertain, but they surely trace back many millennia. So, the concept of Basque migration could be considered at least as old as the existence of historical references.

First Basque migration waveFirst Basque migration wave

It is well established that, during the Roman Empire, there were generations of Basque soldiers allied to the Romans who took part in many wars in different areas of the Empire[1]. Certainty exists of Basques fighting already in the Social War (91-87 BC) in today's Italy, as part of the Turma Salluitana cavalry unit under the orders of Gnæus Pompeius Strabo. His son, Pompey the Great, is known for having used Basque lands as a haven during the Sertorian civil wars fought in Hispania. [2] More than a century later, in 68 CE, Roman emperor Galba recruited a whole legion in Iberia (known as Legio VII Gemina) in which at least one Cohors Secundæ Vasconum[2] existed, formed of Basque soldiers who were active for more than a century and fought in different parts of the empire (today's Germany, Britain,[3] Morocco...).[1] Basques would thus settle in different parts of the Empire, after acquiring Roman citizenship due to various services -including military ones.[4]

Moving into the Middle Ages, it is well known that the main Basque migration pattern was interior to the Iberian peninsula and had to do with Reconquista, by which certain populations from Basque lands were incentivized to move south to repopulate territories which had been conquered by Christian kingdoms from Islamic ruling. This replicates a general North-South movement of population, characteristic of Iberia during the Middle Ages, that correlates well with genetic patterns as studied by.[5] However, a systematic study of Basque emigration that generates noticeable traces of a “diaspora” can only be started with migration waves that stem from the era of the Spanish Empire and its spreading across the globe. Obviously this means that the main (and most ancient) communities of Basque migrants heavily overlap with countries that were part of the Spanish Empire. Following the thesis of [6], three main Basque migration waves can be differentiated. The first one lasted for the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, where “Basques enjoyed leading positions all over the American colonies, constituting themselves as a self-aware ethnic group, and formed migration chains that were based on cultural peculiarities and an 'ancient and strong tendency towards mutual union of those originated in Vasconia, based in turn on a conciousness of its collective identity and communitarian singularity'”.[6]

This first wave is generally associated with political and economic elites of the Empire, along with successful traders and merchants, and ultimately also men who would go deep into the new lands to create commercial outposts, build new towns and take possession of the territories on behalf of the Spanish monarchy. Once these families of Basque ancestry were settled in South America, Mexico, Cuba, the Philippines etc. and became relevant administrative figures, they would in turn facilitate the arrival of new Basque migrants.

Second Basque migration waveSecond Basque migration wave

The second wave is associated with a different profile of migration with took place in the 19th century. The pattern was markedly distinct because the situation and the developments throughout the century were certainly divergent from the ones in the previous 300 years: continental Spain, including the Basque Country and Navarre, was invaded by France in 1808 and, although by 1814 the Napoleonic armies were definitively expelled from Spain, a process had been started of independence of the colonies in America, such that by 1829 most of the Spanish Empire did not exist anymore. The only remnants were Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and some territories in the Pacific and Africa. As if the loss of a global empire was not enough, Spain went through its own civil wars (1833-1840, 1846-1849 and 1872-1876) and on the economic front fell behind other European economies, remaining mostly and agrarian society versus other countries that embraced the Industrial Revolution. his wave of migrants was still directed mostly at the same countries as the first one (since obvious cultural links still made them the first choice for Basques), but it consisted of peasants and impoverished workers seeking for jobs, or refugees from the wars that took place in Spanish soil. It is estimated that in the 19th century until the 1930's there were a total of 200,000 Basques emigrating just to the Americas.[7]

Third Basque migration waveThird Basque migration wave

A third wave can be further identified after the start of the Spanish civil war in 1936, which would extend into the 1940's and 1950's during dictatorship in Spain. Beyond Basques escaping economic hardship -although such a profile was still present-, political refugees became the main migrants to the Americas, who also brought a much higher level of politicisation to Basque communities abroad (see [6]). Apart from the countries mentioned below, other countries such as Mexico,[8] [9][10] Cuba,[11][12] Venezuela,[13] Colombia[14][15] or Uruguay[16] also have relevant presence of Basque diasporas and maintain, to this day, numerous Euskal Etxeak.

Major destinations of Basque emigrationMajor destinations of Basque emigration

Although nowadays there are migrants with Basque origins/ancestry in most countries worldwide, there are number of them in which Basque presence has been historically relevant: not only the genetic footprint and associated unique surnames, but also the feeling of diaspora and cultural ties (including names of many locations which have a root in the Basque language) remain to this day.

ChileChile

Chile has been called “the Basque-Araucanian country”; famous Modernist writer Miguel de Unamuno once said There are at least two things that clearly can be attributed to the Basques: the Society of Jesus [the Jesuits] and the Republic of Chile. In this South American nation (with a population of 20 million) it is estimated that between 10% [8] and 40% [9] -depending on the sources- of the people are of Basque descent. Although the presence of Basques is as old as the Almagro expedition from 1535 and the Valdivia Conquest of 1540, it is during the 1700's that Basque immigration arrived massively to Chile, giving way to the Castilian-Basque aristocracy that still exists nowadays -and has exercised notable social and political power- in family names such as the Allendes, the Balmacedas, the Carreras, the Larraíns, and the Vergaras. A list of paternal and maternal family names of Chilean presidents -since its independence in 1826- looks like a list of Basque surnames: Larraín, Eyzaguirre, Arechavala, Vicuña, Irisarri, Errazúriz, Aldunate, Mascayano, Zañartu, Garmendia, Balmaceda, Echaurren, Luco, Andonaegui, Oyanedel, Urrutia, Aguirre, Arancibia, Iribarren, Allende, Ugarte, Azócar, Echenique... Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda's real name when he was born was Ricardo Neftalí Reyes Basoalto, where Basoalto is also a Basque surname.

Basque presence in Chile is at the core of its national identity (and elites) so it would be difficult to speak of a proper diaspora; in any case the main Chilean institution that preserves ties and union between Basques and Chile is the Euzko Etxea Chile, founded in 1912 in Santiago. There are plenty of monographies about Basques in Chile available;[17][18] the latter of which includes 5 volumes on Basque-Chilean genealogies.[19]

ArgentinaArgentina

Argentina has been a major migration place for Basques, since the early 16th century but massively in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is estimated nowadays up to 10% of the Argentinian population is of Basque descent. The capital city of the country, Buenos Aires, was founded by Basque conquistador Juan de Garay in 1580.

Many Argentinian presidents have been of Basque descent: Justo José de Urquiza, Santiago Derqui, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Luis Sáenz Peña and his son Roque, José Evaristo Uriburu and his nephew José Félix, Manuel Quintana, José Figueroa Alcorta, Victorino de la Plaza, Hipólito Yrigoyen, Roberto Marcelino Ortiz, Ramón Castillo, Juan Domingo Perón and his popular wife Eva Duarte Ibarguren, Pedro Eugenio Aramburu... the number of Basque toponyms in Argentina is also high: the main airport in the country is Ezeiza (the name coming from afluent Basque-Argentinian José María Ezeiza), two more districts of Greater Buenos Aires have Basque names (Berazategui and Esteban Echeverría), along with many other places just in the Buenos Aires city and province (General Madariaga, Necochea, Olavarría, Villa Luzuriaga, Villa Urquiza, Zárate...).

Argentina holds many Euskal Etxeak (Basque Centers): local institutions in different locations across the country with a main mission to preserve Basque culture, history, language and traditions in the diaspora. Almost 90 Basque Centers exist nowadays in Argentina, and every year they organize the SNV (Semana Nacional Vasca or Basque National Week) which hosts people from all over the Americas and Basque regions.[20] The Basque-Argentinian Juan de Garay Foundation has published a monography about Basques in Argentina[21] with thousands of family names. Other sources provides a history about Basque presence in Argentina and its impact.[22]

United StatesUnited States

United States would not seem a major destination for Basque migration, but in the 19th century there were waves of Basque migrants into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range of California, across the Sierras into the neighboring area of northern Nevada, and into Idaho.

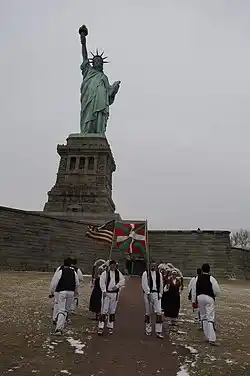

The largest concentrations of Basque Americans are in Boise, Idaho[23] and Reno, Nevada.[24] There are more than 30 Basque Centers in the US, all coordinated by NABO (North American Basque Organizations). The Jaialdi festival is celebrated every 5 years in Boise and is considered to be the largest Basque festival in the world, with tens of thousands of attendees. Worth mentioning, the William A. Douglass Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada (in Reno) has been conducting research on the Basques and disseminating the results of their interdisciplinary activities to a local, national and international audience.

PhilippinesPhilippines

The Philippines is the Asian country with the closest relation to Basques, since they comprised maybe the largest part of Spanish expatriate population during the Spanish colonial period (1565 to 1898). Basques became part of the local society as soldiers, sailors, merchants, clergy and missionaries of the Catholic faith. A number of Basque descendant families remain influential in the business and political sectors of the country: the Aboitiz, the Zobel de Ayala, the Aranetas, the Zubiris, the Ozamiz or the Elizaldes.[25] For a well known text on Basque presence in the Philippines, see Basques in the Philippines.[26]

Organisations supporting the Basque diasporaOrganisations supporting the Basque diaspora

The Basque Government[27] and the Government of Navarre[28] keep a close relation with the many entities of the Basque diaspora worldwide. To a lesser extent, also the French Communauté d’Agglomération Pays Basque, created in 2017, supports relations with Basques all over the world.[29] Also in France, the Institut Culturel Basque encourages the development and influence of Basque culture.[30]

As explained before, there are numerous Euskal Etxeak, Basque Clubs, Basque Centers etc. across all continents which are important spaces for the preservation and diffusion of Basque culture. They organize parties, events, conferences, etc. so that the language, gastronomy, music and folklore of the Basques is transmitted to attendees from all corners of Basque diaspora. There is a list of the many entities available.[31]

The Basque Government is responsible for the organization, every four years, of the World Congress of Basque Communities.[32] It also has designated September 8th as the Basque Diaspora Day internationally. The date commemorates the feat of Basque sailor Juan Sebastián Elcano,[33] who was the first person to circumnavigate the globe in 1522. Already mentioned are the local events Jaialdi in the United States and the SNV in Argentina.

Legacy and cultural influence of Basque emigrationLegacy and cultural influence of Basque emigration

Impact of Basques in the countries to where they migrated since the Middle Ages has been profound. While keeping their own language and Catholic faith in many cases, Basque migrants used to integrate themselves in their new homelands and identities. At the same time, many instilled the ideas of freedom and fighting for self-determination in their countries of adoption.

A list of important figures of Basque descent may provide some insight on their relevance for the countries that adopted them:

- Simón Bolívar (1783-1830) was a Venezuelan descended from an affluent and well known family of Basque origins. The Bolívar family name stems from the Ziortza-Bolibar municipality in Biscay. Simón ultimately led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia to independence from the Spanish Empire. He is called “El Libertador” for that.

- Ernesto "Che" Guevara (1928-1967) was a famous Argentine revolutionary of Basque descent. The Guevara family name originated in Álava. Ernesto participated in historical events for the countries of Guatemala, Cuba, Congo and Bolivia. He is one of the most widely recognized figures of the 20th century.

- José Mujica (1935-2025) was a very popular president of Uruguay for 5 years. He descended from Basque ancestors.[34] Specifically, the Mújica family name originated in the Gipuzkoan municipality of Beasain.

- Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810-1884) was an Argentinian political theorist who is considered the father of the Argentinian Constitution of 1853 (which is still current). Juan Bautista's father was a Basque trader born in Getaria, Gipuzkoa.

- Some other famous presidents of American countries which had Basque ascendancy were Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (President of Cuba between 1940 and 1959; he was forced out by Fidel Castro-led revolution), Salvador Allende (President of Chile from 1970 to 1973, who died during a coup d'etat) and Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (who ruled over Chile as a dictator from 1973 to 1990).

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Basque emigrationExplore more about Basque emigration

Additional materials on Basque migrations and diaspora are numerous and relatively easy to be found online. Only a fraction are in English language, though.

- The Basque Government published the Uranzadi collection on Basque migrations and diaspora, a total of 31 volumes between 2003 and 2018, which are available for free in. It also has a project on an Archive of the Basque Diaspora.

- William Anthony Douglass was born in Reno, Nevada, in the United States in 1939. He is a renowned anthropologist who led the Center for Basque Studies at the University of Nevada (in Reno) from 1963 to 2000. In 1975 he published the first edition of Amerikanuak : Basques in the New World,[35] which was an instant success. In 2006 he released Global Vasconia: essays on the Basque diaspora;[36] there are some other works in the matter published by the University of Nevada.[37][38][39]

- The University of the Basque Country has published many articles,[40] and also offers specific postgraduate studies on the Basque diaspora.

- Basque American Blas Pedro Uberuaga maintains a fantastic resource online with many topics on Basque culture, sports, music, as well as diaspora and genealogy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 García y Bellido, Antonio Los “vascos” en el ejército romano. Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta, ISSN 0046-435X, Year 1, No. 1, 1969; Pages 97-107 (in Spanish).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cohors Secundae Vasconum. Roman Britain

- ↑ R. W. Davies. MILITARY DECORATIONS AND THE BRITISH WAR. Acta Classica: Proceedings of the Classical Association of South Africa, ISSN 2227-538X, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1976; Pages 115-121.

- ↑ Los Romanos. Historia del País Vasco y del Euskara

- ↑ Bycroft, C., Fernandez-Rozadilla, C., Ruiz-Ponte, C. et al. Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula. Nat Commun, ISSN 2041-1723, 10, Article # 551, 2019.

- ↑ Tsavkko Garcia, R. Basque Diaspora in Latin America: Euskal Etxeak, Integration and tensions. European Diversity and Autonomy Papers - EDAP, ISSN 1827-8361, Vol. 2016(1), 1-26.

- ↑ Álvarez Gila, Óscar and Angulo Morales, Alberto. Las migraciones vascas en perspectiva histórica (siglos XVI-XX). Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco, 2002. ISBN 9788483734476

- ↑ Martínez Salazar, Ángel and San Sebastián, Koldo. Los vascos en México: estudio biográfico, histórico y bibliográfico. Txertoa, D.L. 1992. ISBN 9788471482686 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Ruiz de Gordejuela Urquijo, Jesús. Los vascos en el México decimonónico, 1810-1910. Real Sociedad Bascongada de los Amigos del País - Gobierno Vasco. Colección Ilustración Vasca, Tomo XVIII, 2008. ISBN 9788493503208 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Garritz, Amaya (coord.). Los Vascos en las regiones de México, siglos XVI a XX. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México - Ministerio de Cultura del Gobierno Vasco [etc.], 6 Vols, 1996-2002. ISBN 9789683657442 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Irigoyen Artetxe, Alberto. La Asociación Vasco Navarra de Beneficencia de La Habana y otras entidades vasco-cubanas. Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, Col. Uranzadi #27, 2014. ISBN 9788445733394 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Douglass, William A (Coord). Vascos en Cuba. Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2015. ISBN 9788445733769 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Three Basque migrations to Venezuela over 500 years of history. About Basque Country

- ↑ Kerexeta Gallastegui, J. and de Abrisqueta, F. Vascos en Colombia : apellidos vasco-colombianos. Ed. Oveja Negra, 1985. 2 Vols. ISBN 9789580609513 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Ricaurte Cartagena, J. A. Los Vascos en Antioquia durante el Reinado de los Austrias (1510-1700). Ed. Centro de la Cultura Vasca Gure Mendietakoak, 2015. ISBN 9879584669998 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Iturria, R. Aporte vasco al Uruguay: Vasconia Uruguayensis. Institución de Confraternidad Vasca Euskal Erria, 2017. ISBN 9789974917446 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Oyanguren, Pedro. Vascos en Chile, 1520-2005 : Euzko Etxea de Santiago. Eusko Ikaskuntza, Col. Lankidetzan Vol. 42, 2007. ISBN 9788484190639 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Laborde Duronea, Miguel. Los Vascos en Chile 1810 – 2000. Santiago, 2002 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Legarraga Raddatz, Patricio. Los Vascos de Francia en Chile (3rd ed. Vols. I - VI). Ka2, 2021 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Avance de la Semana Nacional Vasca de Argentina 2025, que se celebrará en Tandil. Euskaletxeak.eus

- ↑ Goyenechea, Mauricio, et al. Los vascos en la Argentina: Familias y Protagonismo. 4th ed. Fundación Vasco Argentina “Juan de Garay”, 2011. ISBN 9789872580834 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Irianni, Marcelino. Historia de los vascos en la Argentina. Ed. Biblos, 2010. ISBN 9789507868115 (in Spanish).

- ↑ Bieter, John P., and Mark Bieter. An Enduring Legacy : The Story of Basques in Idaho. University of Nevada Press, 2000. ISBN 9780874175684.

- ↑ Saitua, Iker. Basque Immigrants and Nevada’s Sheep Industry : Geopolitics and the Making of an Agricultural Workforce, 1880-1954. University of Nevada Press, 2019. ISBN 9781943859993.

- ↑ Lezaun Iturralde, Mikel. Los Elizalde, filipinos de Irurita. Antzina, ISSN 1887-0554, #37, June 2024; Pages 25-37 (in Spanish).

- ↑ De Borja, Marciano R. Basques in the Philippines. University of Nevada Press, 2005. ISBN 9780874178838.

- ↑ Dirección para la Comunidad Vasca en el Exterior. Acción Exterior y Euskadi Global. Lehendakaritza

- ↑ Navarra presenta sus políticas sobre diáspora en el Pleno del Consejo General de la Ciudadanía Española en el Exterior. Gobierno de Navarra

- ↑ Célébration de la cinquième journée internationale de la diaspora basque. Pays Basque Euskal Herria

- ↑ Basque diaspora, the eighth province. Institut Culturel Basque

- ↑ Diáspora vasca

- ↑ Congresos Mundiales de las Colectividades Vascas en el Exterior. Lehendakaritza

- ↑ Facaros, Dana; Pauls, Michael (2008). Bilbao & the Basque Lands. Cadogan Guide. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-86011-400-7.

- ↑ The Uruguayan president finds his Basque roots. Agencia EFE

- ↑ Douglass, William A. and Bilbao, Jon. Amerikanuak : Basques in the New World. University of Nevada Press, 2005. ISBN 9780874176254.

- ↑ Douglass, William A. and University of Nevada, Reno. Center for Basque Studies. Global Vasconia: essays on the Basque diaspora. William A. Douglass Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, Reno, 2006. ISBN 9781877802676.

- ↑ Totoricagüena, Gloria P. Identity, Culture, and Politics in the Basque Diaspora. University of Nevada Press, Reno, 2004. ISBN 9780874175479.

- ↑ Oiarzabal, Pedro. The Basque Diaspora Webscape: Identity, Nation, and homeland, 1990s–2010s. Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, Reno, 2013. ISBN 9781935709411.

- ↑ Totoricaguena, Gloria P. Basque Diaspora : Migration and Transnational Identity. Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada, 2005. ISBN 9781877802461.

- ↑ The Group: general overview. PAÍS VASCO, EUROPA Y AMÉRICA: Vínculos y Relaciones Atlánticas