The term Basque genealogy applies to family research associated with individuals with ancestry in either the Spanish or French Basque Country or their descendants. In Spain, the Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre show a unique blend of elements that make them one the most desirable spots for deep genealogical research. While a large part of this article focuses on genealogy that pertains mostly to the three Basque provinces of Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa, most of it, however, can be considered applicable to Navarre, and only partially to the French Basque Country.

Factors that set apart Basque genealogy from othersFactors that set apart Basque genealogy from others

Being part of mainland Europe, written records exist from the Early Middle Ages. However, unlike other European countries, large-scale invasions of the Iberian Peninsula only happened in 711 AD (Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula) and 1807 (Napoleonic invasion). So, for almost 11 centuries there was no massive destruction of documents and archival infrastructure (granted, there were many smaller-scale wars, sieges, partial invasions etc. on Spanish -and Basque- soil). Also, as part of the Spanish Empire -the first truly global monarchy-, there was huge bureaucracy already in the 16th century. Philip II (who ruled over the Spanish Empire from 1556 to 1598) was especially fond of a humongous bureaucratic administration that he contributed to create, so much so that some historians refer to the Spanish crown of the time as the monarquía papelera (i.e., paper or ‘papery’ monarchy)[1]. This circumstance is behind the existence of numerous records of all kinds in most Spanish provinces, including Basque regions, to this day.

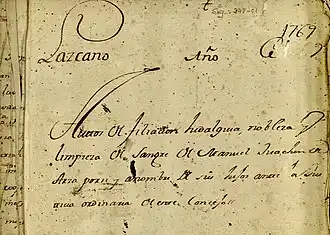

Specifically in the Basque regions, there was the principle of Hidalguía Universal (universal lesser nobility). This meant that Basques had certain privileges, stemming from the fact that the Spain of the final Middle Ages and early Modern Age gave a lot of relevance to “purity of blood”[2]. Since the Umayyad conquest of Hispania did not reach Basque territories, it was believed Basques had maintained their original purity, a racist concept of the time to refer to those considered ‘Old Christians’ by virtue of not having Muslim, Jewish or Romani ancestors. Thus, people who could show pure Basque ancestry were automatically considered hidalgos (i.e., lowest nobles) and exempt from paying taxes[3]. From a genealogical perspective, this gave rise to a whole range of documents, the expedientes de hidalguía (patents of nobility), in which people would litigate to show their Basque ancestry (e.g., when they moved residence to a different town in which they wanted not to pay taxes)[4]. There are tens of thousands of these documents still available, from as early as 1442 to as late as 1835, which give precise lineage information for all litigants (e.g. see examples litigated in 1582 in Biscay[4] and in 1733 in Gipuzkoa[5]).

The Basque Country, along with the rest of Spain, remained Catholic throughout Medieval and Modern times, thanks to the efforts of the Spanish Inquisition. This simplifies research of church records since there is only one primary source to consider (the Catholic Church), and there is a continuity in records to this day. As in other European Catholic countries, church records start in general after the Council of Trent, which finished its work in 1563. However, as in some parishes in France and Italy, there are earlier church records in Spain. Some Basque parishes have church records dating back to the late 15th century.

Types of Basque historical recordsTypes of Basque historical records

Different types of records form the backbone of any genealogical research in the Basque Autonomous Community (provinces of Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa). They will be analyzed one by one.

Catholic Church recordsCatholic Church records

See also: Basque church records

Records owned by the Church are the main primary source for Basque genealogy. Most people who were born after 1563 in any of the three provinces were baptized, so they probably have a baptismal record, and if they married, they are likely to have a marriage record preserved. Lastly, a sizable percentage of the population will have a death/burial record too. In 1999, the Government of the Basque Autonomous Community entered into an agreement with the three Roman Catholic Dioceses of Vitoria, Bilbao, and San Sebastián so that all records from all parishes would be concentrated in one centralized archive per diocese. Furthermore, the Basque Government would invest so that all records older than year 1900 would be digitized, indexed and the indexes made publicly available online.

Civil recordsCivil records

See also: Civil records in the Basque Country

The Civil Registry in Spain was established in 1870, following two previous attempts in 1823 and 1841, and went into effect on January 1, 1871. Since then, the Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre have kept track of births, marriages, and deaths. However, Catholic Church records, which were used until 1900, generally provided similar information during the 1871-1900 period, making the Civil Registry less useful at the time. These records became freely accessible to citizens by law in 1986, but they have not been digitized or made available online. Requests can be made via a specific webpage, and certificates, if available, are mailed upon request, with generic reasons such as "gestiones personales" usually sufficing.

Notarial recordsNotarial records

See also: Notarial records in the Spanish Basque Country

Notarial records in the Spanish Basque Country are valuable historical documents that provide a unique perspective on the region's social, economic, and legal history. The Escribanos (who would change their name to Notarios in 1862 and are known as Notarioak in Euskera) have been creating these records since the medieval period to document various legal transactions such as property sales, wills, contracts, and disputes. Notaries played an important role in ensuring the authenticity of these documents, which were used as evidence in court and for personal purposes. The preservation of these records is invaluable, as it provides researchers with detailed information about family history, business transactions, and regional customs. As a result, notarial archives in the Basque Country are invaluable resources for understanding the region's cultural history. These records are available at centralized archives on each one of the provinces of the Basque Country, as well as on the Archive of Euskadi.

Other recordsOther records

Many other types of records exist that are useful for Basque genealogical research, beyond Church or Notarial Records. Several of them can be queried through the same means as explained before for Notarial Records.

One example is the population census. There were many censuses carried out in parts of the Spanish Basque Country during the centuries. The so called “fogueraciones” started already in the 16th century and are unique of Biscay and parts of Álava (complete ones exist at least for the years 1704, 1745 and 1790), and in the 19th century there is the very interesting Censo de Policía from 1825. Electoral censuses start from at least 1854. In most cases they identify people individually, with at least one surname; a number of them can be searched here just by querying “censo electoral”.

Municipal records can be a treasure of information, but they are not always available online and few have a searchable database. One example is the Archive of Bergara in Gipuzkoa.

Family records have also existed in the Basque Country for a long time, and they can be the source of interesting genealogical information. Many important families associated with surnames such as Areizaga, Ruiz de Arcaute, Saenz de Tejada, Zavala, Irizar, etc. have their archives available through the same search engines described above for Notarial Records.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about Basque genealogyExplore more about Basque genealogy

Beyond traditional Basque primary sources, there are several secondary sources that may prove useful for the researcher. Some of them will be discussed here -and bibliography provided-. Many of them are in Spanish.

- Spain, Bilbao Diocese, Catholic Parish Records, 1501-1900 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Biscay, Baptisms record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Biscay, Deaths record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Vitoria Diocese, Index of Deaths, 1573-1904 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Vitoria Diocese, Index of Marriages, 1559-1899 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Vitoria Diocese, Index of Baptisms, 1535-1903 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Navarre, Census, 1816-1935 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Navarre, Index of Deaths, 1592-1986 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Navarre, Index of Baptisms, 1559-1910 record collection at MyHeritage

- Spain, Navarre, Index of Marriages, 1577-1940 record collection at MyHeritage

- Basque Genealogy project Dashboard at Geni

- How to Research Your Ethnicity with Genealogy on the MyHeritage Genealogy Hub

- Non-profit Antzinako is a voluntary association for Basque genealogy and local history. They publish a magazine Antzina every 6 months. Their focus is more on Navarre (since it lacks a single source for indexed Catholic Church records) and Gipuzkoa. In the Database section of their webpage, they have a very complete data base of “Lineages” with alphabetically ordered Basque surnames and complete analysis of their lines.

- Like the Lineages above, amateur genealogist Antonio Castejón (recently deceased) tirelessly compiled thousands of Basque lineages throughout the years, and they can be freely accessed here. Specific to some regions in the Basque Country, similar initiatives by amateur genealogists exist in the case of Debagoiena (one of seven regions in Gipuzkoa) or around Bergara, or in the Ayala region in Álava.

- Lists of Basque surnames can be useful to identify when a surname is of Basque origin. One example can be found here, and a book with some 10,000 Basque surnames here. Another list with surnames that were part of expedientes de hidalguía in the past can be found here. Basque Academy Euskaltzaindia offers a complete database of Basque first names, surnames and place names here.

- There are many books around Basque genealogy and Basque surnames[6] [7]. One obvious reference, just for its sheer size, is the well-known Enciclopedia heráldica y genealógica hispano-americana by brothers Arturo and Alberto García Caraffa, published in 88 volumes from 1919 to 1963 and which tried to list and document every Spanish surname alphabetically. In 1963 the last of the brothers died, so the encyclopedia was still unfinished (at letter “U”); Basque author Endika de Mogrobejo took on finalizing it with the publication of another 15 volumes since 1995 (titled Diccionario hispanoamericano de heráldica, onomástica y genealogía) and then, from volume 16, started a whole review of the encyclopedia again (still unfinished as of 2024). The García Caraffa brothers themselves, being aware of the importance of Basque surnames for Spanish genealogy and heraldry, published a 6-volume work only for Basque surnames[8].

References

- ↑ Marc André Grebe. Akten, Archive, Absolutismus? Das Kronarchiv von Simancas im Herrschaftsgefüge der spanischen Habsburger (1540-1598). Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft, 2012. https://doi.org/10.31819/9783954870004

- ↑ https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0101.xml

- ↑ Lourdes Soria Sesé. La hidalguía universal. Iura vasconiae: revista de derecho histórico y autonómico de Vasconia, ISSN 1699-5376, Volume 3, 2006, Pages 283-316.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Llorente Arribas, Elena. Hijosdalgo e hidalguía vascos en las reales chancillerías. Pruebas jurídicas, historiografía y archivística. Vasconia: Cuadernos de historia - geografía, ISSN 1136-6834, Volume 46, 2022, Pages 5-30.

- ↑ Urcelay, Jaime (2017-05-29). "Los pleitos de hidalguía en Guipúzcoa. Expedientes del apellido Ucelay o Urcelay (I)". Blog de Jaime Urcelay (in español). Retrieved 2024-07-31.

- ↑ Guerra, Juan Carlos de. Ensayo de un padrón histórico de Guipúzcoa. Ed. Joaquín Muñoz-Baroja, 1928.

- ↑ Kerexeta, Jaime de. Diccionario Onomástico Y Heráldico Vasco. Bilbao, Gran Enciclopedia Vasca, 8 vol. 1998.

- ↑ Alberto García Carraffa, Arturo García Carraffa. El solar vasco navarro (3rd ed.). Librería Internacional, 1966.

<link rel="mw:PageProp/Category" href="./Category:Spain" /> <link rel="mw:PageProp/Category" href="./Category:France" />