Black Wall Street[1] aka the Greenwood District[2] in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a term coined by Booker T. Washington[3] was the brainchild of (Ottaway) O. W. Gurley[4], a formerly enslaved man from Arkansas. In 1906 he purchased 40 acres of land, selling only to freedmen. His idea was to create an environment where freedmen could prosper. Along with J. B. Stradford[5], a businessman, they provided the tools to launch and sustain businesses with startup loans, advice and investment capital. Gurley also built the Gurley Hotel where he rented out space to smaller businesses. Their model was that community members were of a single mind, to help one another prosper. Add to that, the forever pumping nearby oil fields created jobs, Tulsa and therefore Greenwood benefitted.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

The Growth of Black Prosperity in OklahomaThe Growth of Black Prosperity in Oklahoma

With a large working-class population as well as doctors, lawyers, and other professionals Tulsa’s Greenwood District became one of the most prosperous African American communities in the United States. Between 1910 and 1920, the Black population in the area grew from 2,000 to nearly 9,000.

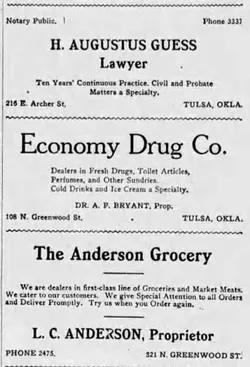

Despite the new legislation guaranteeing equal rights, the residents knew that laws would not change the hearts and actions of those who saw them as inferior. The restrictions put on Greenwood’s and other African American communities by the greater white community helped Greenwood prosper by forcing them to become creative as well as self-sufficient. One of the firsts was providing a grocery store that attracted other African Americans traveling to the area. Originating in 1912 as the Muskogee Star, editor and publisher Andrew Jackson Smitherman[6] took the direction of his former employer, the Muskogee Cimeter, expanded on its focus of African American life and culture and moved it to Greenwood, rebadging it in 1913 as the Tulsa Star[7]. The newspaper acted as a community hub, advertising what was going on in Greenwood and other African American communities around the country. Included were world events, a society page spotlighting citizens, local news, culture and advertisements for colored businesses, all allowing them to prosper and stay connected.

There were 190 businesses owned and operated in Greenwood, including Elliot Furnishings, Clothing and Shoes, the Masonic Lodge, a Black employment agency, Vernon AME Church, the Stradford Hotel, the Gurley Hotel, European Hotel Melrose, Nichols Hardware Company, Dreamland Theatre, Goodner Malone Fruit, National Survey Company, Bradford Pipe & Supply, the Palace Barber Shop, Harvey Young Oil, Christ Temple, the Red Wing Hotel and the Zulu Lounge among others. The Tulsa Star carried Greenwood advertisements for some of the community businesses including the Red Wing Café, the Palace Barber Shop and others. There was also a Colored Business Directory so that all of their needs could be handled within the community.

Opportunities Following ReconstructionOpportunities Following Reconstruction

After the realities of post-Reconstruction became apparent, freedmen needed to find a way to feed themselves, their family and flourish. Remaining in the South limited the progress that could be made despite the new laws in place. Changing the mindset of a people who were used to reaping their economic benefits from the free labor of African Americans was not the reality. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan[8], the Black Codes[9] and Jim Crow[10] were all barriers put in place to keep freedmen from progressing.

The Homestead Acts[11][12] offered all Americans including African Americas an opportunity to fulfill their dreams. Once the 5 Tribes[13] received their land allotments then the surplus land was made available for settlement. Newspaper articles and word of mouth signaled the nation that new land and freedom was available for anyone willing to make the sacrifice and head to Oklahoma.

Oklahoma Gains StatehoodOklahoma Gains Statehood

On November 16, 1907, Oklahoma became the forty-sixth state under President Teddy Roosevelt[14]. The oil fields guaranteed the state’s future prosperity. The influx of people from across the nation also meant segregation and Jim Crow followed with sundown towns being established. The very thing African Americans had fled from was once again amongst them.

Difficult Paradigm Shifts for SomeDifficult Paradigm Shifts for Some

White residents continued the separations from blacks, while resenting the self-sufficiency, prosperity and lack of passivity exhibited by Greenwood residents. As a result of mass migrations to the area, driven in part by increased job opportunities, Tulsa became the city with the most African Americans in the state. As more and more people flooded the area ready for opportunity and equality, whites had little time to adjust. Tensions began to rise. Coming from societies where whites were considered superior, seeing blacks prosper was hard to digest.

It hadn't been long since slavery had been abolished, stereotypes were easily embraced. White Tulsa newspapers regularly referred to the Greenwood district in derogatory terms labeling African Americans in the district as boozers, dopers, and running around with guns. The engrained hatred created fear and distrust amongst the white population.

Catalyst to DestructionCatalyst to Destruction

In 1921, the Tulsa Tribune (white newspaper) reported the attempted rape of a white woman by a black man. Neighboring white residents used the news as an opportunity to lash out and attacked the community. Greenwood residents responded to protect themselves and their community. For two days whites attacked the community, burning thirty-five blocks of Greenwood, resulting in three hundred deaths and eight hundred injuries. The police only arrested blacks, holding them in detention centers. No whites were ever detained.

Sometimes called the Tulsa Race Massacre[15], the community of Greenwood was devastated. A Tulsa Race Riot Commission recommended reparations for “people who lost property” and proposed “the establishment of a scholarship fund—that did happen, for a limited time.” The commission also proposed initiatives for the economic revitalization of the Greenwood community. Despite the tragic events, these grand ideas never manifested into a tangible reality.

The Legacy of GreenwoodThe Legacy of Greenwood

The Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma, earned its name as the "BlackGreenwood Historical Marker Wall Street," through the demonstrated prosperity, pride and resilience of its people in the early 20th century. This thriving community was a testament to the entrepreneurial spirit and determination of its residents, who built a self-sufficient economy despite the challenges of segregation and racial discrimination.

Greenwood's prosperity provided a sense of pride and empowerment for the formerly enslaved and their descendants, demonstrating the potential for economic success and community development even in the face of systemic racism. The district's flourishing economy and vibrant culture made it a beacon of hope and a model for other Black communities across the United States at a time when all odds were against them.

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the Black Wall StreetExplore more about the Black Wall Street

- Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, 1791-1963 record collection at MyHeritage

- Researching Oklahoma Roots webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Black Wall Street USA

- O. W. Gurley. Black Past

- Black Wall Street, Before During and After the Tulsa Race Massacre. History Channel

References

- ↑ Black Wall Street | Tulsa Library

- ↑ https://blackwallstreet.org/ourhistory

- ↑ Booker T. Washington ‑ Biography, W.E.B. Dubois & Facts | HISTORY

- ↑ https://blackwallstreet.org/owgurley

- ↑ John "the Baptist" Stradford (1861-1935) •

- ↑ The Tulsa Star (Tulsa, Okla.) 1913-1921 | Library of Congress

- ↑ Tulsa Star - The Gateway to Oklahoma History

- ↑ Ku Klux Klan | Definition & History | Britannica

- ↑ Black Codes ‑ Definition, Dates & Jim Crow Laws | HISTORY

- ↑ Jim Crow Laws: Definition, Facts & Timeline | HISTORY

- ↑ Homestead Act (1862) | National Archives

- ↑ Public Land: Whose Land is It?

- ↑ https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=FI011

- ↑ https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/theodore-roosevelt/

- ↑ https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/