The movement of freedmen[1] after Reconstruction[2] from middle Tennessee to Kansas with its free state status and proximity to a large waterway became known as the Exoduster Movement[3] or Exodus of 1879. Taking place mostly between 1869 and 1881, freedmen to a larger degree left Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, often using the Mississippi River and connecting waterways as part of their transportation route. From men with masks and weapons robbing, threatening and turning them back; to merchants along the way refusing to sell them food and supplies; to river boat captains charging exorbitant fees and sometimes kicking them off the steamboat before arriving at their destination, the journey was fraught with obstacles.

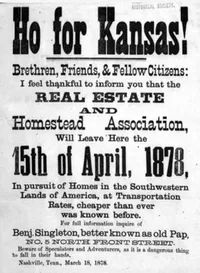

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton[4], a skilled promoter and self-appointed spokesman for the Exodusters, is most notably connected to the movement, though he did not do it alone. Numerous resources prove that there were many who heeded the call of available land and the opportunity for a new life, free from the residue of slavery. Countless hands and brilliant minds helped pave the way for Black migration and the realization of the American Dream. Some were famous advocates while others worked diligently without recognition, assisting those around them and others in need. Singleton, like others looked toward a bright future for freedmen, rejected making labor agreements with former enslavers. Instead, they advocated land ownership, political freedom and self-sufficiency.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

Preparing for KansasPreparing for Kansas

Newspapers are a great source of the Exoduster history. According to an article in the April 30,1879 issue of the Memphis Daily Appeal, an exploratory team was sent to Kansas in 1872 to determine the viability of Negro migration to the area. After gaining a positive view, Pap Singleton and others, pleased with what they'd found, made the necessary preparations and escorted 200-300 freedmen to Kansas. Upon settling in Cherokee County, the settlement became known as Singleton Colony. In an issue of The Emporia Newspaper dated May 14, 1878, Singleton’s first, second and third trips from Tennessee to Kansas yielded a total of 1,769 freedmen delivered safely. In all, Singleton is credited with moving nearly 8,000 freedmen to Kansas. Not everyone was able to establish homesteads in Kansas. This led to settlement in larger towns such as Topeka, where the African American community became known as Tennessee Town[5].

The CatalystThe Catalyst

Available land in Kansas and other states was the result of the Homestead Act of 1862[6] which offered settlers 160 acres of free public land on the Great Plains. With little to no protections from the government when federal troops were pulled out after Reconstruction ended, attacks on freedmen from white supremacy groups such as the Ku Klux Klan[7] increased dramatically. The possibility of life without terror on the Great Plains was a chance they needed to take for survival. It was also a way to exercise their full rights of citizenship and land ownership. Open to US citizens, freedmen, new immigrants, single women, and people of all races, for a small processing fee, commitment of time and sweat equity the American dream could be realized. For many formerly enslaved, it meant relocating from the South, embarking upon a new life and a chance to take care of their family.

In theory, the Homestead Act was an opportunity to escape the racism and oppression, not only of the South but from all the places that turned a blind eye to the rampant inequities that plagued non-whites. The reality was much different. As people followed, so did their biases.

The Southern Homestead Act of 1866The Southern Homestead Act of 1866

This act, part of the Reconstruction era, opened up federal land in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi for settlement, offering the same promise as the original act. Settling land in these Southern states presented the same problems for freedmen as before, continued inequities and abuse despite guarantees.

Oklahoma Also Offers New PossibilitiesOklahoma Also Offers New Possibilities

Edward McCabe[8], a lawyer, politician and land speculator from New York, ventured to Oklahoma Territory in 1890, where he founded a town exclusively for black settlers called Langston[9] with promises of a utopia where “the colored man had the same protection as his white brother.” Named for John Mercer Langston[10], one of the Black politicians of the Reconstruction era who took office as the first Black Virginian to serve in the United States House of Representatives. Langston’s principal founders were McCabe, William L. Eagleson[11], editor of the Colored Citizen, the first Black owned newspaper in Kansas, and Charles W. Robbins, a white land speculator.

One cannot discuss Oklahoma during this period without mentioning Massachusetts Senator Henry Dawes[12]. He led a commission in 1893 which ultimately led Congress, in a series of forced negotiations, to force the Five Tribes[13] to convert more than 15 million acres of land to individual ownership. Tribal members became U.S. citizens by government mandate and opened them up to swindlers preying on them because of their historic views about land.

The Kincaid Act of 1904The Kincaid Act of 1904

The Kinkaid Act[14] expanded the Homestead Act allowing individuals to claim 640 acres of land in Nebraska's Sand Hills. DeWitty, Nebraska[15] was founded in 1907 by runaways and their descendants who’d escaped before the Civil War to Canada. Later named Audacious, in its heyday, the settlement had a famous baseball team called the North Loup Sluggers[16], which competed against teams from nearby communities. The community also had a church, store, barber, post office and three rural schools. DeWitty had a good relationship with neighboring Brownlee, sharing an Independence Day tradition of festivities including a rodeo, baseball game, and picnic.

In Nebraska, as expansion increased, so did conflict between ranchers and homesteaders. The ranchers embraced the idea of the open range for grazing. The homesteaders embraced the idea of ownership thus fencing in their land and reducing land for open cattle grazing. Many a Hollywood movie has been made about these conflicts and the bloodshed surrounding them. The conditions made homesteading in the area difficult causing some to move on.

Black Communities Formed Due to the Homestead ActBlack Communities Formed Due to the Homestead Act

A number of communities populated exclusively with African Americans popped up during this period of available land. The National Park Service has placed some of these towns on their registry, providing documentation where there was little. Some of note follow:

Nicodemus, Kansas[17] was the Promised Land advertised to Southern freedmen looking for a new start. W. R. Hill, a white land developer from Indiana and Rev. W. H. Smith[18], a black man formed the Nicodemus Town Company, with Rev. Smith as president and Hill as treasurer. Their promoting and advertising worked, and settlers began to come. Unfamiliar with the rigors of winter, a lack of adequate tools, housing and food, they suffered greatly. The Osage Indians[19] were of assistance, but the starkness of the area and lack of vegetation contrasted greatly with land freedmen were accustomed to.

Dearfield, Colorado[20] was founded in 1910 by Oliver Toussaint Jackson[21], an African American leader and entrepreneur when he filed a homestead claim for the initial 160 acres of land.

Blackdom, New Mexico[22] became the state’s first African American community. Founded by homesteader Francis Marion Boyer[23], who was seeking escape from the terrors of the Ku Klux Klan. By 1908, the town had a thriving population of 300, supporting local businesses, a newspaper and a church. By the late 1920s, crop failures and other calamities, caused a decline in population.

Norvel Blair[24] founded the “Sully County Colored Colony[25]” in South Dakota Territory in 1884. Victims of racism, his family was swindled out of their land, robbed of their accumulated wealth and barred from voting. Fed up, Blair sought a better life by filing a homestead claim on the banks of the Missouri River in Sully County, South Dakota. The family bought up property abandoned after the gold rush. His daughter, a realtor, sold to other African Americans. The town boasted 200 residents and had a livery stable, restaurant and more. In 1894 Blair received special recognition from the St. Paul and Duluth Railroad for saving a number of passengers during a train fire. In 1896, his stepson, Benjamin became the first African American to serve on a school board in South Dakota, holding the post of chairman of the Fairbank school district for ten years.

Empire, Wyoming[26] had the distinction of being settled by homesteaders who left Dewitty, Nebraska where the land was difficult to farm. One such person was Lizzie Speese[27], one of two women who homesteaded in the area. She acquired her land through the Desert Land Act[28]. After significant improvements and with the help of her family, she built a frame house, a root cellar, and a sod hen house, along with a barn and a cow shed. In her final proof, she estimated her improvements to be worth over $1,500.

Other names contributing to the Exoduster Movement include Columbus Johnson, who worked with Pap Singleton, Rev. Russell Taylor,[29] an Empire Wyoming homesteader, postmaster, religious and educational leader; and O. W. Gurley[30], the founder and driving force behind Greenwood, Oklahoma aka Black Wall Steet[31].

See alsoSee also

Explore more about the Exodusters Embrace the Homestead ActExplore more about the Exodusters Embrace the Homestead Act

- Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, 1791-1963 record collection at MyHeritage

- United States Newspapers from OldNews.com™ record collection at MyHeritage

- Researching Oklahoma Roots webinar at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Kansas Settlers – Pioneers Settling Prior to 1900 webinar at Legacy Family Tree webinars

- Home on the Range: Kansas Research Tips webinar at Legacy Family Tree webinars

- Edwards, Richard. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.17681895 Great Plains Homesteaders. University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books. 2024.

- Kranz, Rachel; Koslow, Philip; Kranz, Rachel. Biographical Dictionary of Black Americans. Checkmark Books, an Imprint of Facts on File, Inc. New York. 1999.

- The Unrealized Promise of Oklahoma. Smithsonian Magazine

- Pap Singleton. Tennessee Encyclopedia

- University of Nebraska- Lincoln. Center for Great Plains Studies

- The Black Politicians of Reconstruction | The History You Didn't Learn. TIME

- The Unrealized Promise of Oklahoma. GCSE History by Clever Lilli

- April 15, 1878: Real Estate and Homestead Association Relocated - Zinn Education Project

- Carey, Bill. The Tennessee Magazine. September 1, 2013. Former slave born in Nashville was leader in Exoduster movement

- Reeves, Matthew. "Singleton, Benjamin “Pap”". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library.

- Chronicling America. Library of Congress

References

- ↑ Freedman Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster

- ↑ Reconstruction ‑ Civil War End, Changes & Act of 1867 | HISTORY

- ↑ Exodusters & Western Expansion | National Archives

- ↑ https://www.uniquecoloring.com/articles/benjamin-singleton

- ↑ TN History For Kids » Exodusters (KS)

- ↑ Homestead Act: 1862 Date & Definition | HISTORY

- ↑ Ku Klux Klan | Definition & History | Britannica

- ↑ https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=MC006

- ↑ https://cityoflangston.com/pages/about-the-langston-city/

- ↑ John Mercer Langston | Abolitionist, Educator, Lawyer | Britannica

- ↑ William Lewis Eagleson (1835-1899) •

- ↑ Henry Laurens Dawes | Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ Five Civilized Tribes | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

- ↑ https://www.nebraskastudies.org/en/1900-1924/reforming-beef/public-land-whose-land-is-it/

- ↑ https://history.nebraska.gov/marker-monday-dewitty-an-african-american-settlement-in-the-sandhills/

- ↑ http://ushighway83.blogspot.com/2016/08/two-new-photos-of-dewitty-emerge-what.html

- ↑ https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ks-nicodemus/

- ↑ https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/nicodemus-town-company-founded/

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/articles/osage.htm

- ↑ https://www.historycolorado.org/location/dearfield

- ↑ https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/oliver-toussaint-jackson

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/places/blackdom-new-mexico.htm

- ↑ Welcome to Blackdom: The Ghost Town That Was New Mexico’s First Black Settlement | Smithsonian

- ↑ https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/blair-norvel-1825-1916/

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/places/sully-county.htm

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/places/empire-wyoming.htm

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/people/lizzie-speese.htm

- ↑ Desert Land Entries.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nps.gov/people/reverend-russel-taylor.htm

- ↑ O. W. Gurley (1868-1935) •

- ↑ https://daily.jstor.org/the-devastation-of-black-wall-street/