European colonization of the Caribbean occurred intensively between the first arrival of the Spanish to the region in the 1490s down to the nineteenth century. For the first century of the European age of colonization the Spanish were the only major force involved in Caribbean colonization. Their impact was disastrous for the native Carib and Taino people, who proved to be particularly susceptible to European diseases like measles and smallpox and died in huge numbers in the first half of the sixteenth century. As a result, the Spanish brought in settlers from Spain and slaves from West Africa to provide forced labor. In the seventeenth century the English, Dutch, French and Danish became involved after a huge boom in the production of sugar cane to feed the European market. By the nineteenth century the demographic landscape of the Caribbean had been completely transformed, but such was the level of slave labor imported that the predominant demography became people of West African heritage alongside those from Spain, France, England, the Dutch Republic and Denmark.[1]

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

European colonization of the Caribbean chronology of eventsEuropean colonization of the Caribbean chronology of events

The Caribbean was where Christopher Columbus initially made landfall in 1492 and indeed his subsequent voyages on behalf of the Spanish crown were largely concerned with further exploring and mapping the Caribbean. It was here that the Spanish Empire first emerged, with colonies on Hispaniola, Cuba and several of the smaller islands acting as a springboard for further conquest of Central and South America from the late 1510s onwards. The Spanish arrival, though, was devastating for the native Carib and Taino people who inhabited the many islands of the region. They had no resistance to European diseases such as smallpox and measles and died in huge numbers once exposed to these. A smallpox epidemic around 1518 was particularly brutal and by the middle of the sixteenth century the native population had declined by around 90%.[2]

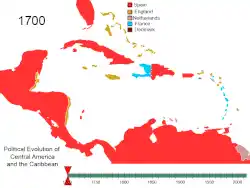

Throughout the sixteenth century the Spanish more or less had a monopoly on colonization of the New World, though the English, French and Dutch were beginning to map the Caribbean and identify islands they might colonize. In the middle of the seventeenth century they did so extensively. The Spanish would remain the pre-eminent power, controlling all of Cuba and two-thirds of Hispaniola, by far the two largest islands, while also retaining control over Puerto Rico and Trinidad.[3] The English eventually acquired control over Jamaica, the Bahamas, Barbados and small chains like the Cayman Islands, Saint Nevis and Kitts and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The French muscled in on Hispaniola and acquired the western end of the island, as well as Guadeloupe, Martinique and several small territories. The Dutch colonized Curacao, Aruba, half of Sint Maarten and a handful of smaller islands like Bonaire and Sint Eustatius. The Danish entered the speculation in Caribbean colonies late in affairs and only obtained the small islands of St Thomas, St John and St Croix.[4]

These European powers would remain dominant across the Caribbean until the nineteenth century. The first colony to obtain its independence was the French colony on Hispaniola, which acquired its independence as Haiti in the early nineteenth century after a lengthy war of independence. The Dominican Republic emerged on the Spanish parts of the island in the decades that followed. After many attempted independence movements in the nineteenth century, Cuba finally gained its freedom from Spain after the Spanish-American War of 1898. Puerto Rico became an overseas territory of the United States as a result of the same war and has the same status today, over a century and a quarter later.[5] The larger British colonies like Jamaica (1962), the Bahamas (1973) and Barbados (1966) were granted their independence during the wave of British decolonization which occurred in the aftermath of the Second World War. Many of the other smaller colonies like the Cayman Islands, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Curacao and Aruba remain under British, French or Dutch control as overseas territories or departments with varying levels of independence. Denmark sold its islands to the United States in 1917.[6]

Extent of colonization of the CaribbeanExtent of colonization of the Caribbean

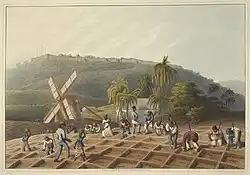

The Caribbean experienced a larger amount of European settlement in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than did other parts of the New World, comparatively speaking. This was because of the boom in sugar cane and other ‘groceries’ like tobacco, coffee and tea in Europe in the early modern era. Sugar, which can be produced in abundance in the Caribbean climate, was particularly valuable and explains why powers like France, the Dutch Republic and England showed such an interest in acquiring control over even quite small Caribbean islands. As they did so tens of thousands of English, French, Dutch and Danish colonists moved out to the various colonies they had obtained. There were, for instance, over 20,000 people of British birth or heritage living on Jamaica by 1800.[7] The most intensively colonized region, however, was Cuba, which had been the capital of the Spanish Empire for a period in the Americas for a time in the early sixteenth century. These colonies also drew settlers from other locations. For instance, there were thousands of Irish settlers who headed to the Caribbean in search of their fortune in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, while many more were forcibly removed there as indentured servants.[8]

As significant as this European colonization of the Caribbean was during the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it paled in comparison with the level of forced African re-settlement which occurred here. The boom in sugar cane created a need for labor in the Caribbean, particularly so as the native Taino and Carib populations, that would otherwise have been enslaved and made to work on these plantations, had been virtually wiped out in the sixteenth century by the disease epidemics. In order to obtain labor as cheaply as possible, the colonial powers began importing slaves from West Africa to the West Indies from the mid-sixteenth century onwards. The Transatlantic slave trade became particularly intense in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Of the nearly 13 million slaves who were officially transported across the Atlantic to the Americas between 1500 and 1860, some 4.7 million were brought to the Caribbean. Hence, European colonization of the Caribbean went hand-in-hand with a much more extensive forced re-settlement of West Africans in the West Indies.[9]

Demographic impact of European colonization of the CaribbeanDemographic impact of European colonization of the Caribbean

European colonization of the Caribbean, and in particular the Transatlantic slave trade, transformed the demography of the region. While there were over 20,000 people of British heritage on the island of Jamaica by 1800, there were over 300,000 slaves. When the Haitian Revolution began in 1791, the French colonial population was slightly more than 30,000, but there was an estimated half a million slaves or former slaves.[10] Today the Taino people who inhabited many of the islands in 1492 are considered to broadly no longer exist, while the Carib and other native groups make up only a fraction of the total population of the Caribbean. Instead over half of the 44 or so million inhabitants of the islands are descended from African slaves forcibly traded to the Caribbean between 1492 and the mid-nineteenth century, while a great proportion of the others are descendants of Spanish, British, Dutch, French, Danish, Irish and American settlers, with the Spanish having left a particularly large imprint in Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Few parts of the world have had their demographic landscape as completely altered by European colonization as has the Caribbean.[11] The vast majority of people living in the Caribbean today will be able to trace their ancestry to people who have arrived to the region since 1492.

Research your ancestors on MyHeritage

See alsoSee also

Explore more about European colonization of the CaribbeanExplore more about European colonization of the Caribbean

- Caribbean, Births and Baptisms, 1590-1928 records collection on MyHeritage

- Caribbean, Marriages, 1591-1905 records collection on MyHeritage

- Caribbean, Deaths and Burials, 1790-1906 records collection on MyHeritage

- Analyzing Probate Records of Slaveholders to Identify Enslaved Ancestors at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Confirming Enslaved Ancestors Utilizing DNA at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

- Descendants of the Enslaved and Enslavers - Working Together to Discover Family at Legacy Family Tree Webinars

References

- ↑ Eric Williams, From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean, 1492–1969 (New York, 1984).

- ↑ https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-were-taino-original-inhabitants-columbus-island-73824867/

- ↑ Ida Altman and David Wheat, The Spanish Caribbean and the Atlantic World in the Long Sixteenth Century (Omaha, 2019).

- ↑ https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/genderedlives/chapter/chapter-12-the-caribbean-introducing-the-region/

- ↑ https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/spanish-american-war

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z4dyvwx

- ↑ https://runaways.gla.ac.uk/minecraft/index.php/the-plantation-system-of-the-british-west-indies/

- ↑ Nini Rodgers, ‘The Irish in the Caribbean, 1641–1837’, in Irish Migration Studies in Latin America, Vol. 5, No. 3 (November, 2007), pp. 145–155.

- ↑ https://news.emory.edu/features/2019/06/slave-voyages/index.html

- ↑ https://revolution.chnm.org/exhibits/show/liberty--equality--fraternity/slavery-and-the-haitian-revolu

- ↑ https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/legacy-slavery-caribbean-and-journey-towards-justice